Director Christian Petzold’s movie “Transit” is set in a timeless France overflowing with refugees from various countries who, while flanked by advancing military forces, are attempting to flee the country.

Although the film evokes the Holocaust — the occupying army is from Germany, and there are references to “the camps” — we never hear the word “Nazis” or see swastikas, and only one of the many ambiguous characters admits to being Jewish. We’re told that some of the refugees are intellectuals and writers, but we’re left to guess why they are attempting to take flight.

That said, the setting clearly is not in the 1942 timeframe depicted in Anna Seghers’ 1944 novel of the same name, which inspired the film. The story appears to take place in the present, but it’s devoid of computers and cellphones.

The German-born Petzold, 58, told the Journal in a telephone interview that he was deliberately vague about the film’s era, as he tried to create a “conversation between a historic time and the contemporary world.”

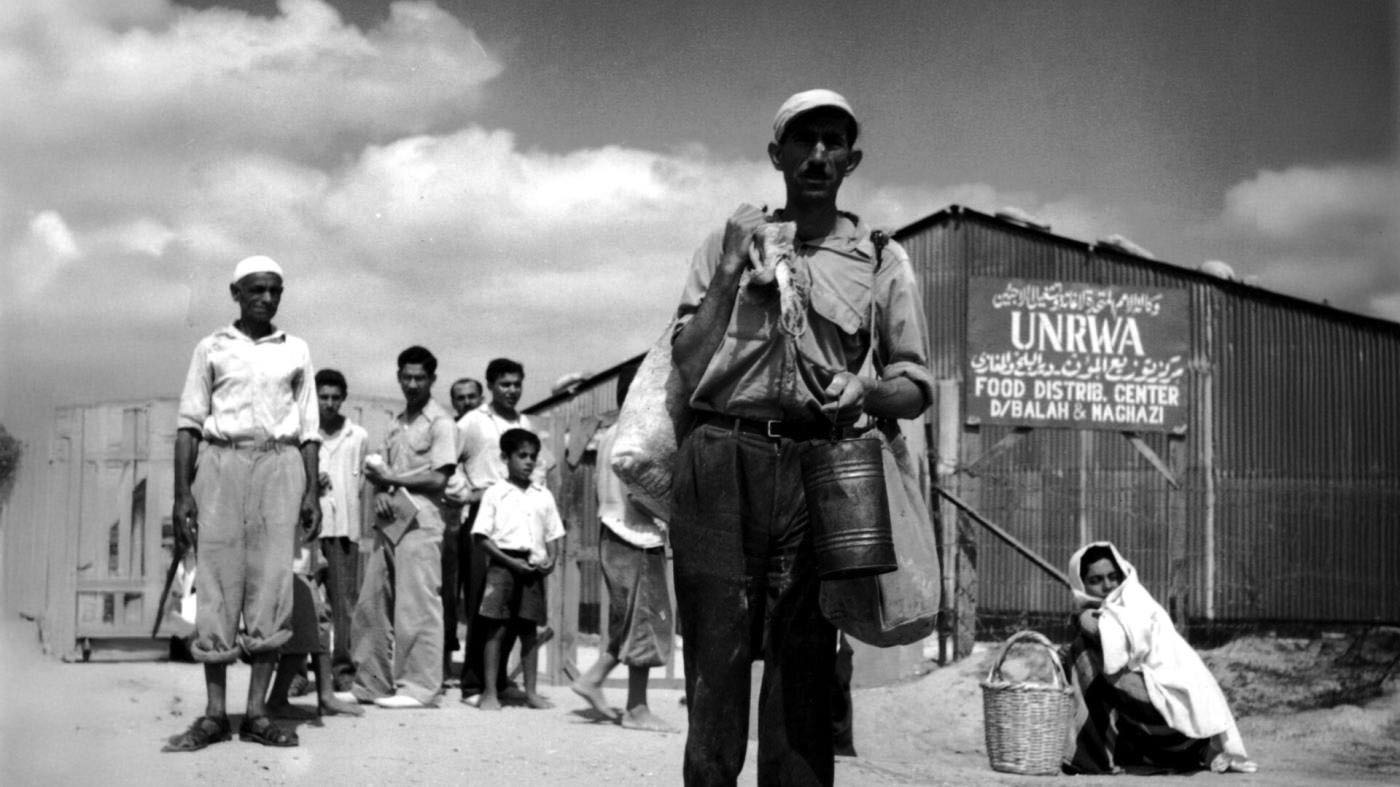

“I’m not saying that all refugees are the same,” Petzold said. “They’re totally different. In fact, I don’t really know very much about today’s refugees. I know much more about the refugees fleeing in 1942 because of the literature that I’ve read and because my own family talked about them. Still, refugees face many of the same responses from countries across the world that say, ‘We don’t need you. We don’t want you.’ Refugees live in camps or are put in prisons.”

Petzold said he found it ironic that today’s enlightened Germany is seeing an upswing in anti-Semitism. He attributed the increased expressions of bigotry to the rise of global capitalism, whose critics channel their hate and anger into virulent anti-Semitism. In times of crisis, he said, people in power will always use Jews as targets for their aggression.

Winnowing the 300-page novel into the screenplay was a complicated feat, Petzold said. One challenge was that, while the first half of the novel was set in Paris, Petzold wanted to focus on the location of the book’s latter half, Marseille, among people in transit who need to reinvent themselves as a survival tactic.

“All refugees try to be storytellers like Primo Levi,” Petzold said, referring to the Italian Jewish chemist, writer and Holocaust survivor who wrote several books, including his account of being a prisoner in “Survival in Auschwitz.” “They try to write something down that they can’t write down. I try to show people who find new identities as a lover, father or friend.”

To the extent that the characters succeed, there’s hope. Petzold believes the film concludes on an affirmative note.

“I love it when characters at the end of the film don’t need me — an audience member — anymore,” Petzold said. “That’s a happy ending. And as the credits roll we hear the [band] Talking Heads, singing [“Road to Nowhere,” with the lyrics, “Well we know where we’re going, but we don’t know where we’ve been”]. It makes me feel that for the first time in my life I’m in a good church whose doors are open. You have a song in your head. You feel you can go outside with a tune.”

Simi Horwitz is an award-winning writer based in New York.