I’ve grown increasingly cynical of the way the Jewish college experience is discussed in our community. Over the last decade, millions have been invested on initiatives, organizations and programs designed to equip our young people with the resources to defend themselves in “the war of words”: The increasing prevalence of anti-Israel activism on campus.

I myself have contributed to this effort. Since The New York Times published my 2019 opinion piece detailing the antisemitism I experienced at my own university, I’ve spoken to countless synagogues, schools, and community centers– trying to explain the problem and offer solutions. And yet the problem only seems to be getting worse. Torahs are vandalized in fraternity houses, Hillel buildings are graffitied, Jewish students are bullied, and resolutions are passed by student governments singling out Israel for boycotts—of course, all under the thin veil of “criticism of Israel.”

After spending more time than I’d like to admit thinking about this issue, I’ve come to appreciate two helpful concepts: the Eicha problem and the Rebbe’s Solution.

Several years ago, novelist Dara Horn spoke to an audience of Jews about a phenomenon she calls the “Eicha problem,” alluding to the book of Eicha, which documents the destruction of Jerusalem by Babylonian armies some 2,500 years ago. Curiously, Eicha portrays not Babylon but the exiled Jews as the villains of the story, and proceeds to blame the Jews and our sins against God for the malady.

Horn calls the Eicha problem “a profound Jewish historical illness,” a compulsion among our people to hold ourselves responsible for the aggression against us. Whether it be Jews in Europe chastising their own lackluster observance of Torah after a bloody pogrom or Israelis giving land back to Arab armies hoping for a ceasefire in the genocidal war against them, it’s hard to miss the historic popularity of Eicha as we have fought and bargained for survival.

It’s also hard to miss how the echoes of Eicha still resonate with our contemporary sensibilities, as we focus on our own real or imagined culpability when reckoning with the rising animosity we face in academic spaces and beyond. Many of us also want to avoid rocking the boat, causing too much trouble. We’d rather be seen as mediators and negotiators—even peacemakers—rather than the ones making a fuss. But this Eicha impulse, however well-intentioned, can often backfire and become even more dangerous to our community than the actions of antisemites.

While touring Jewish life at Brown University last month, I was privy to a meeting of The Narrow Bridge Project, a “student cohort experience which meets to discuss the past, present and future of Jewish peoplehood, Zionism and antisemitism, our differing definitions of each of these, and how these differing understandings impact our Judaism, activism and life experiences as Jews today.” I couldn’t help but be amused by this elaborate description — reminded of how I do not miss college at all.

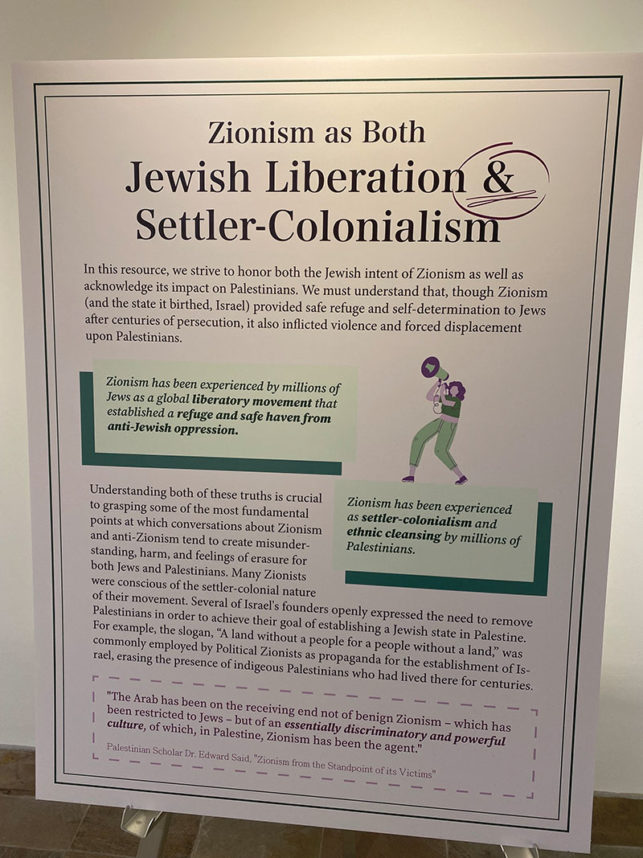

That night, the students involved in this work, seeking to “facilitate more productive discussions about antisemitism amongst all people, Zionists and anti-Zionists in particular,” were celebrating the release of their book, a years-in-the-making compilation of resources intended to educate college students on how to acknowledge and honor the Jewish experience while also seeking justice for Palestinians. Lining the main hallway of the venue were large placards, the first one reading “Love Thy Neighbor: A Guide for Tackling Antisemitism While Committing to Justice for All.” Another read “Zionism as both Jewish Liberation & And Settler Colonialism” and another read “How We Critique Zionism and Israel.”

The intentions of The Narrow Bridge Project were no doubt pure. Of course, in the face of multiple antisemitic incidents occurring on their campus over the last several years, Jewish students at Brown, like our wider Jewish community at large, were compelled to act. Students at this event spoke of how meaningful it was to hear other points of view on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and organizers cautioned with inspiring words against approaching tough issues with fear.

But it should go without saying that Palestinian and/or Muslim students were notably absent from this event, as The Narrow Bridge Project’s application was extended only to Jewish students. I have found that Jewish students who are not explicitly anti-Zionist activists love nothing more than to sit with one another to discuss and to argue, to heal the world, to hammer out solutions and “dialogue.” We aren’t afraid to have hard conversations, and we aren’t afraid to disagree with one another.

The problem is that others, those automatically against anything related to Israel, love nothing more than to paint such activities as evil for normalizing Zionism as they work instead toward banishing Israeli scholarship from the library. So, while well-meaning Jewish activists meditate on the best solutions to bridge divides, the other side does the very opposite. It doesn’t even bother to show up.

While well-meaning Jewish activists meditate on the best solutions to bridge divides, the other side does the very opposite. It doesn’t even bother to show up.

You can see this one-sided obsession especially with J-Street U, the collegiate branch of the larger organization J-Street. J-Street U likes to market itself as “pro-Israel” and “pro-peace,” yet each of their initiatives over the last several years have been working to combat Israeli wrongdoing, such as the settlement project or the absence of Palestinian educators on Birthright trips. J-Street U’s work always seemed like a march toward justice to me, until I arrived on campus, and realized that students involved rarely aligned themselves with the Jewish majority when Israel’s existence itself was attacked on campus.

J-Street U activists are notoriously against adopting the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, are usually silent (or among the opposing team) during Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) debacles, and are often quiet when blatant antisemitism, not criticism of Israel, balloons from organizations like Students from Justice in Palestine.

Regardless whether these left-leaning students still believe in a Jewish sovereign state with protected borders, they, in line with our forefathers, have placed themselves under higher standards than the Jewish world’s adversaries, who in this case seek quite openly to push Jewish life off campus and out of progressive spaces. In other words, J-Street U falls victim to the Eicha Problem. “If you want to believe in a just God,” says Horn, “you have to believe that your suffering is somehow deserved.”

“We have a Beit Midrash on Thursday nights and a Jewish Learning Fellowship, established by many students who came back from gap years hungry for Jewish higher learning. The energy has caught. People know about us.”

— Rabbi Joshua Bolton, Executive Director of Brown-RISD Hillel

Later in my visit to Brown, I was able to meet with some more assertive Zionist students who did not obsess over trying to engage the other side. These students were less interested in meeting with members of Jewish Voice for Peace and more interested in describing Jewish life at Brown. One of the key takeaways from our conversations was that there has been an uptick in observant Jewish students in the university’s classrooms, widely seen as a positive development.

Rabbi Joshua Bolton, the Executive Director of Brown-RISD Hillel, commented on the change: “We went from not having one Orthodox Shabbat minyan to now having it being the most stable minyan. We have a Beit Midrash on Thursday nights and a Jewish Learning Fellowship, established by many students who came back from gap years hungry for Jewish higher learning. The energy has caught. People know about us.”

Christina Paxson, the President of Brown, commented on this change. “As an example of our commitment to an expansive view of religious diversity,” she wrote to me, “in recent years we’ve taken deliberate steps to increase outreach to high school students who attend Jewish day schools, resulting in an increase in applicants, acceptances and matriculating students.”

The more “visible Jews” there are on campus, Brown students confided in me, the more confident other students felt in standing up for Israel.

The more “visible Jews” there are on campus, students confided in me, the more confident other students felt in standing up for Israel. A more pluralistic student experience and the chance to see Judaism in the lecture halls serve as a check on potentially venomous anti-Israel advocacy. An explanation for this? On college campuses, noticing that Jews don’t always blend into the majority because they are wearing kippot or tallit makes activism against them seem less progressive.

I thought of my own school, George Washington University. A few weeks ago, a fraternity home was broken into and a student’s Torah scroll was vandalized. In response, the Chabad chapter on campus rallied one of the largest gatherings of students, Jews and non-Jews, I have ever seen as a response to antisemitism. In what became a singular act of holy defiance, the Kippah-wearing boys led a Torah procession across campus and read Hebrew in the quad surrounded by an impressive crowd. I was nearly moved to tears while viewing the footage, and thought of what a waste of an opportunity it would have been to instead gather students for a conversation on intersectionality or on “diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

At a Brown Chabad service later in my visit, I felt both out of place and right at home—uneasy that this was my first time being in a gender-separated religious space, but welcomed when familiar prayers began. Each of the students around me carried a passion one doesn’t always see in mainstream services, and I was grateful to be among those davening and listening to a Judaic studies major tell us her interpretation of that week’s Torah portion. These students were not at the presentation of how to manage antisemitism; they were too busy being Jews. And from what I kept hearing around campus, Jews of all observance levels felt safer and stronger because of them.

On the train home from Brown, I thought about the holiday of Hanukkah, and how it has changed in American culture since my family arrived in this country. Traditionally, and like many Jewish holidays, Hanukkah was kept mostly private. The argument was that if Jews began flaunting their religious pride in public spaces, Christians would feel entitled to do the same, and Jews have always favored secular American circles more than ones that enforce a majority’s presence. In the 1970s, however, the Lubavitcher Rebbe decided to campaign for public menorah lightings, a movement that ultimately triumphed, for Hanukkiahs can now be seen everywhere from college campuses to JP Morgan to the White House lawn.

The Rebbe argued:

“Why is it so important for Jews to have a Hanukkah Menorah displayed publicly? The answer is that experience has shown that the Hanukkah Menorah displayed publicly during the eight days of Hanukkah, has been an inspiration to many, many Jews and evoked in them a spirit of identity with their Jewish people and the Jewish way of life. To many others, it has brought a sense of pride in their Yiddishkeit and the realization that there is no reason really in this free country to hide one’s Jewishness, as if it were contrary or inimical to American life and culture. On the contrary, it is fully in keeping with the American national slogan “e pluribus unum” and the fact that American culture has been enriched by the thriving ethnic cultures which contributed very much, each in its own way, to American life both materially and spiritually.”

If the Eicha problem compels Jews to constantly address our own shortcomings to fight antisemitism, the Rebbe’s solution says that only by being prouder, more visible Jews can we ultimately prevail over the evil of Jew hatred. When we strive to help heal the world, we must do so as proud Jews. When we spread the special Light of Hanukkah, we must do so as proud Jews. When we walk through the halls of schools or attend events or seminars, we must do so as proud Jews. When we engage with those who disagree with us, when we delve into complex issues, when we show compassion for the less fortunate, we must do so as proud Jews.

In essence, we must become Proud Jews Walking. Not angry Jews. Not fearful Jews. Not silent Jews. Not self-blaming Jews. But proud Jews.

The essence of a proud Jew is to not be afraid to express one’s Jewish identity, to connect to one’s Jewish heritage and proudly observe Jewish traditions. The freedom to express one’s identity is a deeply American idea that reinforces a great American ideal. Being a proud Jew, then, is not just good for the Jews, it’s also good for America.

When I am asked to describe “the problem” and the solution, my first answer will be to wear a kippah to class, or a Magen David to the party, or put Shabbat candles on the window sill, and walk through the campus and through life as a proud Jew.

The Rebbe was a champion of charity and of building relationships with the non-Jewish world, but this never impeded the most tangible expressions of Judaism. His commitment to all of humanity was through his dedication to Torah and mitzvot, not a substitute for it. Too often we have done the opposite—allowing our need to be embraced by society to swallow up a commitment to actually practicing Judaism.

Students at Brown told me that the presence of more observant and committed Jews enhances their own morale and forces activists to think twice before attacking what is now very clearly a particular minority community in the tapestry of college life. At a time when progressives today are so cognizant of group identity– ethnic, religious or otherwise– the Rebbe’s thinking about wearing our Jewish identities is undoubtedly proving useful.

We must of course continue to fight “the war of words”—the fight for Israel on campus against a slippery ideological foe that gaslights and torments us. But this war will stand no chance unless we liberate ourselves by unleashing our Jewish identities. I realize now more than ever the importance of those who fight by expressing their Jewish identity. They may not yell at demonstrations or use clever Twitter and Instagram messages to defend Israel, but what they do is present themselves every day to their classmates and the world as Jews.

When I am asked to describe “the problem” and the solution, my first answer will no longer be just to read up on our history and to sit and debate and argue and convince. It will instead be to wear a kippah to class, or a Magen David to the party, or put Shabbat candles on the window sill, and walk through the campus and through life as a proud Jew.

Blake Flayton is New Media Director and columnist at the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.