Today, as we celebrate the 70th anniversary of the founding of the State of Israel, it is all too easy to forget how long the Jewish people longed for a homeland and how unattainable it seemed, even on the eve of statehood in 1948. To put it another way, the history of modern Israel is measured in decades, but the idea of Zionism is measured in millennia.

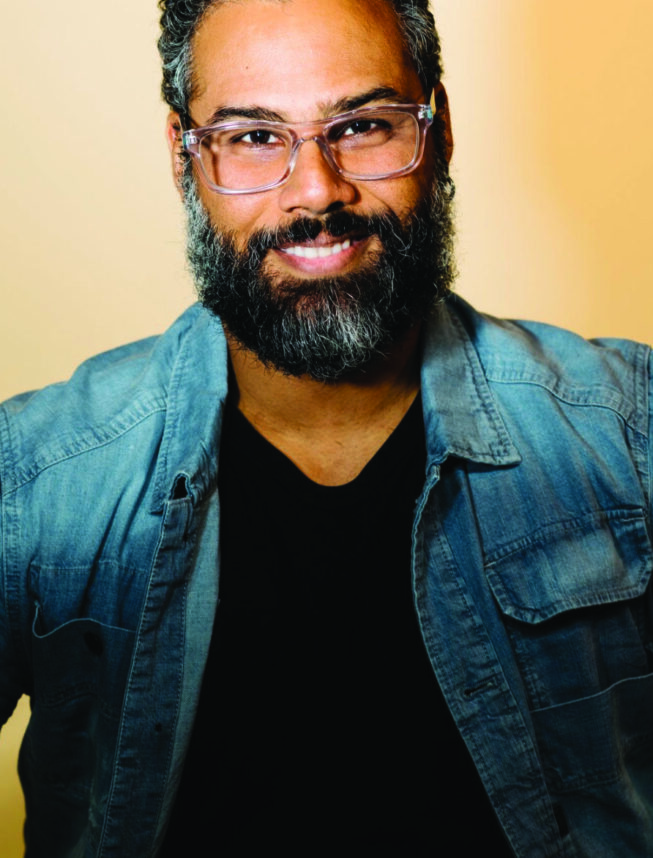

Israel was only 21 years old when Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg’s “The Zionist Idea” was first published. Now the Jewish Publication Society has published what it calls a “renewal” of Hertzberg’s classic text, that is, a new and expanded anthology of writings titled “The Zionist Ideas: Visions for the Jewish Homeland — Then, Now, Tomorrow,” ably edited by Gil Troy, a distinguished scholar of North American history at McGill University and the author of 12 books, including, “Why I Am a Zionist.”

Ironically, perhaps the single most significant difference between Hertzberg’s book and Troy’s book is the addition of an “s” to the title, thus making explicit the notion that Zionism must be — and is — a pluralistic enterprise rather than an article of faith.

“We need a modern book celebrating, as Professor Gil Troy notes, the Zionist ideas: the many ways to make Israel great — and the many ways individuals can find fulfillment by affiliating with the Jewish people and building the Jewish state,” writes Natan Sharansky, one of the modern heroes of the Zionist movement, in his introduction to the book. “A revived Zionist conversation, a renewed Zionist vision, can create a Jewish state that reaffirms meaning for those already committed to it while addressing the needs of Jews physically separated from their ancestral homeland, along with those who feel spiritually detached from their people.”

As Troy explained in an interview with the Jewish Journal (see page 22), “The Zionist Ideas” is something more and something different from the original text, and for more than one reason. Troy managed to reduce the length of the book while, at the same time, expanding the number of contributors (or “thinkers,” as he calls them) and the breadth of the conversation. So we hear more voices, and more varied voices, in “The Zionist Ideas” than we did in the 1959 edition.

Ironically, perhaps the single most significant difference between Hertzberg’s book and Troy’s book is the addition of an “s” to the title, thus making explicit the notion that Zionism must be — and is — a pluralistic enterprise rather than an article of faith.

It’s a project that required not only Troy’s own deep knowledge of Jewish history, politics and culture, but also a healthy dose of chutzpah. “Since 1959, ‘The Zionist Idea’ has been the English speaker’s Zionist bible, the defining text for anyone interested in studying the Jewish national movement,” Troy explains. “To some academics and activists, Hertzberg’s tome was such a foundational work that any update is like digitizing the Mona Lisa or colorizing ‘Casablanca.’ ”

But an update was urgently needed, if only because Zionist conversation has changed from the simple question of whether a Jewish homeland could be achieved — “History’s affirmative answer [is] ‘Yes!’,” writes Troy — to the far more complex question of what the Jewish homeland should aspire to be. “Israel’s 1967 Six-Day War triumph stirred questions Hertzberg never imagined, especially how Israel and the Jewish people should understand Zionism when the world perceives Israel as Goliath, not David.”

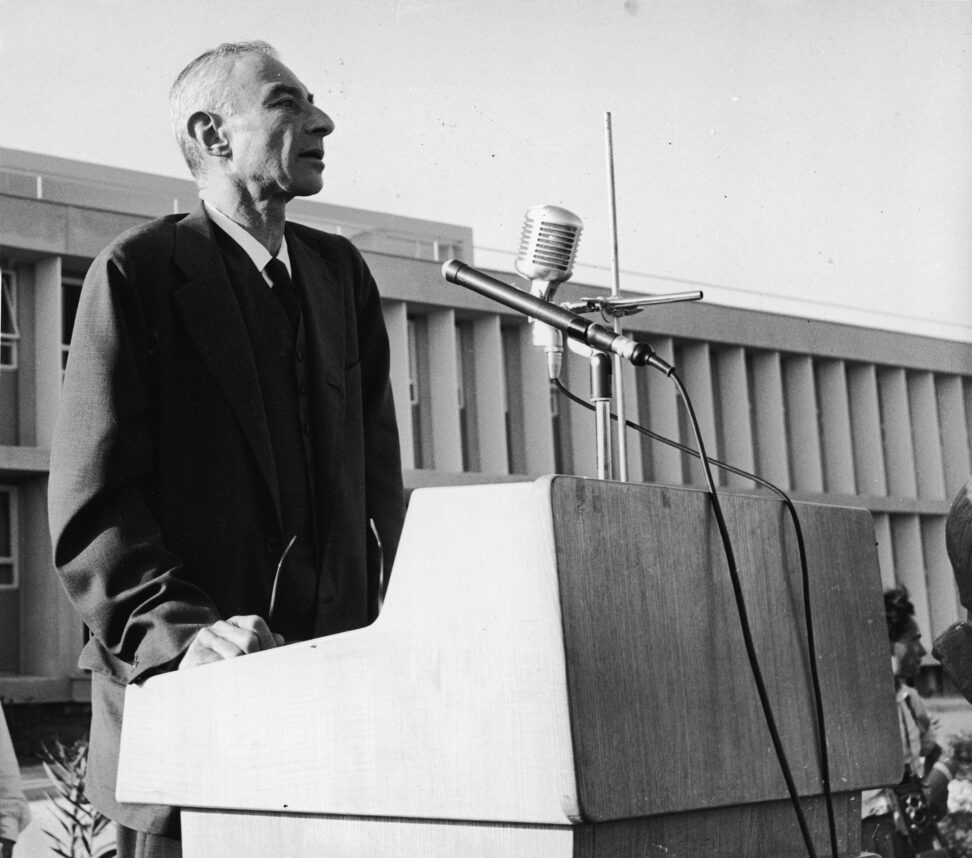

Troy helpfully divides the Zionist movement into six “schools” — Political, Labor, Revisionist, Religious, Cultural and Diaspora Zionism — and he divides the contributors into three categories: the “Pioneers” (including Herzl, Jabotinsky and Ahad Ha’am), the “Builders” (including David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir and Menachem Begin) and the “Torchbearers,” ranging from Peter Beinart to Leon Wieseltier, whose article on the concept of bitzu’ism (which he translates as “implementationism”) transformed my understanding of the Zionist saga history when I first read it in the New Republic in 1985: “The bitzu’ist is the builder, the irrigator, the pilot, the gunrunner, the settler.”

Troy is vividly aware — and wants his readers to be aware — that Zionism is a work in progress rather than a set of commandments carved in stone.

Of course, the very idea of Zionism has always had its nay-sayers, who once included both the Reform movement and the most observant strands of Judaism. Nowadays, Israel is a benchmark of Jewish identity in all branches of Judaism, except a few Chasidic courts. Even so, Troy is vividly aware — and wants his readers to be aware — that Zionism is a work in progress rather than a set of commandments carved in stone.

“Like Abraham’s welcoming shelter, the book’s Big Tent Zionism is open to all sides, yet defined by certain boundaries,” he writes. “Looking left, staunch critics of Israeli policies belong — but not anti-Zionists who reject the Jewish state, universalists who reject nationalism, or post-Zionists who reject Zionism. Looking right, Religious Zionists who have declared a culture war today against secular Zionists fit. However, the self-styled ‘Canaanite’ Yonatan Ratosh … who allied with Revisionist Zionists but then claimed Jews who didn’t live in Israel abandoned the Jewish people, failed Zionism’s peoplehood test.”

And so, like Tevyah, there are limits to his open-mindedness, and the exclusions say as much about the diversity of thought in the Jewish community. “Sadly, the most frequent question non-Israeli Jews have asked me about this book is, ‘Will you include anti-Zionists, too?’ ” he muses. “When feminist anthologies include sexists, LGBT anthologists include homophobes, and civil rights anthologies include racists, I will consider anti-Zionists.”

Troy points out that Abraham’s tent has always been capable of accommodating a Jewish community of remarkable diversity and vitality. Zionism has changed over time, as Troy repeatedly reminds us, starting when Herzl was repudiated by his fellow Zionists for famously proposing Uganda as the site of the Jewish homeland, and continuing without pause as Zionism wrote itself into world history. But Troy also insists that its core values include not only the land of Israel but also the democratic character of the Jewish state itself.

Significantly, one of the documents in “The Zionist Ideas” is the Jerusalem Program of the World Zionist Organization as proclaimed in 1951 and reissued in 2004. The two versions are different in many details, but one aspiration appears in both versions — “a Jewish, Zionist, democratic and secure State of Israel.”

To which Zionists, one and all, are surely able to say: Amen!

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.