Few wars fought on any soil have had as profound an impact as the Six-Day War, which began June 5, 1967. The Jewish Journal asked Jewish leaders and thinkers to assess the war’s aftermath 50 years later.

Six Days, Followed by 50 Years of Palestinian Posturing

The Six-Day War was a turning point. Until then, Arab leaders were all about avenging Palestine; the defeat in 1948 swept the old elites out of power and brought in younger ones from the military. They made Palestine the central issue — not to resolve it but to use it internally and in their rivalries with other Arab leaders to see who could dominate the Arab world. Pan-Arabism — one Arab nation — was the idiom, and Palestine was the vehicle around which it was built. That, for all practical purposes, ended after those six days in June 1967.

Palestinians, who had left their fate to the Arabs after 1948, now knew they could not count on them. Unfortunately, the Palestinian leaders — while claiming they now would assume responsibility for fulfilling national aspirations — found it easier to focus on symbols and not substance, rejection rather than reconciliation, and grievance rather than achievement. Even today, their tendency remains more a flag at the United Nations than state and institution-building. There are those like former Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Salam Fayyad who recognize that the State of Palestine is far more likely to emerge when the rule of law becomes more important than seeking resolutions in international forums that deny the Jewish connection to Jerusalem.

Israelis expected peace after the war. The Cabinet adopted a secret resolution on June 19, 1967, accepting withdrawal to the international border in return for peace with Egypt and Syria. More discussion was needed on the West Bank/Gaza. Israelis had not expected to be occupiers of what at that time were a million Arabs. The Oslo process was supposed to resolve the problem of occupation, but has not.

The challenge now — 50 years after 1967 — is for Israeli leaders to figure out how to avoid becoming a binational state when it is not clear that two states for two peoples can be negotiated, much less implemented, anytime soon.

DENNIS ROSS is a former Middle East envoy and negotiator under four U.S. presidents.

From Auschwitz to Jerusalem and From Jerusalem to …

As the three-week buildup to the Six-Day War began, Jews sensed that Jewish life was again at risk, this time in the State of Israel. Once again, the world was turning its back. The United States would not come to Israel’s aid. The United Nations troops left.

A friend suggested that we bring the Israeli children to the U.S., where they would be safe. I decided that my place was to be in Israel. If the Jewish people were threatened, it was my fight, my responsibility. So instead of attending my college graduation ceremony, I left for Jerusalem. I was in the air when the June war began, and landed in Israel just in time to be in Jerusalem when the city was reunified.

I can still hear the words of the bus radio announcement as it was driving on old Highway 1:

“An IDF (Israel Defense Forces) spokesman has said: The Old City is ours; I repeat the Old City is ours.”

I can still see the tears in the eyes of my fellow passengers as they embraced one another.

On the fifth day of the war, I went to Shabbat eve services and heard then-Israeli President Zalman Shazar speak the words of “Lecha Dodi”: “ ‘Put on the clothes of your majesty, my people. … Wake up, arise.’ All my days I have prayed these words and now I have lived to see them.”

Never were those words more true. Never did they touch my soul more completely. I was a participant in Jewish history; I was at home in Jewish memory; I was embraced by Jewish triumph. However much skepticism — political and religious — has entered my understanding of that war and its consequences in the past 50 years, that moment is indelible in my soul and touched it, oh, so deeply.

My role in the war was anything but heroic. I organized a group of American volunteers to drive and work on garbage trucks. In that capacity, I helped clear the rubble of the war that divided Jerusalem at Jaffa Road and some of the stones from the homes demolished near the Wall. I was there on Shavuot when 100,000 Jews went to the Wall — under Jewish sovereignty for the first time in 1,878 years — and women in miniskirts danced alongside Charedi men, each fully absorbed in the moment, oblivious to the incongruity of what they were doing.

And yet, looking back, I think we are still fighting the Six-Day War, now a 50-years war. The “victory” has lost its majesty and mystery, though not its necessity. Even without walls in the center of Jaffa Street, Jerusalem is a divided city, nationally, ethnically and religiously. Repeated triumphs have not yielded security. The Jewish narrative is anything but simple: From Auschwitz to Jerusalem, and from Jerusalem of Gold to an earthly place divided and dividing. Time has made it more difficult to return to that heroic, miraculous moment -— more difficult but perhaps not less urgent.

MICHAEL BERENBAUM is a professor of Jewish studies and director of the Sigi Ziering Institute at American Jewish University.

Following Maestro’s Advice Changed His Life

Both of my parents are seventh-generation Israelis. On June 3, 1967, I was in medical school in Philadelphia studying for my med boards when the Arabs were surrounding Israel, screaming for its destruction.

I flew to Israel, volunteered as an intern in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), and was stationed in Gaza. On the morning of June 8, my commanding officer, who knew of my family — called “Vatikay Yerushalayim” (“The Ancients of Jerusalem”) — said, “Tzahal [the Hebrew acronym for the IDF] is about to recapture the Old City. Go up to Jerusalem.”

I was there when Rabbi Shlomo Goren blew the shofar on Har ha’Bayit (the Temple Mount). It was the most important moment in my life.

I was then transferred to the Hadassah Medical Center, and Leonard Bernstein came to conduct Mahler’s “Resurrection Symphony” on the newly reconquered Har ha’Tzofim (Mount Scopus).

Bernstein came to visit the volunteers. “You look exactly like a waiter of mine at a discotheque in New York City,” he said to me.

“I am your waiter,” I answered. He immediately invited me to the concert.

Afterward, at the party at the King David Hotel, he offered me a “gofer” job on the documentary film of “the maestro” conducting the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra in Judea and Samaria for the Tzahal, with Isaac Stern playing the violin. It was a war zone and you couldn’t go unless you got special clearance.

Lenny encouraged me to leave medical school: “You are too good of a storyteller. Go into the arts. You will never bow to the Mistress of Science.”

Back in Philly, while assisting on an amputation, I decided to take a leave of absence. I called up Mr. Bernstein and told him, “I took your advice.”

Mr. Bernstein then introduced me to Katharine Hepburn, whose assistant I became on [the Broadway musical] “Coco,” and Stephen Sondheim … and my life was never the same again.

HOWARD ROSENMAN is a Hollywood producer.

An Unexpected Narrative

Eight years ago, I happened to be in Memphis, Tenn., where I visited the National Civil Rights Museum. The guided tour was led by an elderly gentleman, probably in his early 80s, who introduced himself as a civil rights activist and a personal friend of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

As he walked us through the museum, we arrived in the hall showcasing an actual Freedom Rider bus. He proceeded to share with us the story of young students bravely coming to Memphis, in racially mixed groups, to show solidarity with the civil rights movement.

Knowing that many of the courageous riders were Jewish students, I raised my hand to ask his perspective on the role of the American-Jewish community in the civil rights struggle.

His answer has plagued me to this day. He said that at the height of the civil rights battles, the Jewish community had stood side by side with the African-American community, that is, until the 1967 Six-Day War.

During and after the war, he said, the attention and passion of the Jewish community turned completely toward Israel and away from the equal rights struggle in the United States. He went on to say that he, along with the leadership of the civil rights movement, felt completely abandoned and forgotten and continue to feel that way to this day.

Although this was a narrative I had never heard before, it helped explain what may have been the beginning of the deep rift that has taken hold between the Jewish and Black communities in the U.S., as felt and viewed from the perspective of the African-American community. We are still realizing the ripple effects of those momentous six days; this is another ripple that continues to impact our community here in the U.S.

SHARON NAZARIAN is president of the Y&S Nazarian Family Foundation.

Millennials and the War

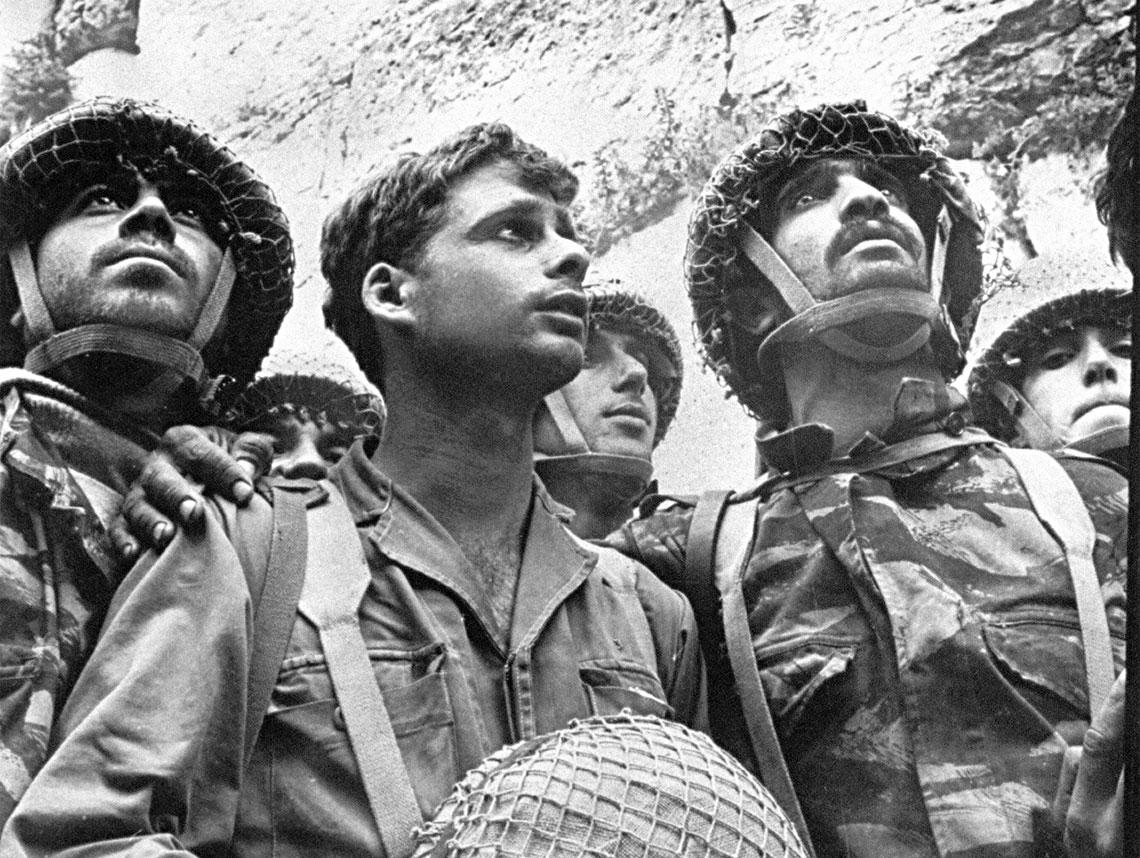

For my parents and many of their friends, the Six-Day War brings to mind David Rubinger’s iconic photograph of Israeli paratroopers standing in front of the Western Wall, their hopeful young faces an indelible reminder of Israel’s miraculous military victory less than 25 years after the Holocaust. But for many millennials, the Six-Day War is not what comes to mind when they think about Israel and the Arab-Israeli conflict. On the contrary, my peers have tended to view Israel largely through the lens of more recent conflicts. As we tell Israel’s story on college campuses and to a new generation of U.S. policymakers, we should keep in mind that Israel’s incredible contributions to science and technology, its vibrant democracy and free press, and its commitment to treating victims of the Syrian civil war are likely to resonate more strongly than its struggle for survival in 1967.

JESSE GABRIEL is an attorney and board member of The Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles.

Six-Day War: A Poem

The war

Became the wall.

But it was also

Families fleeing, fighters dying

Ghosts returning, rejoicing.

The city no longer a widow

The people no longer an orphan.

The tangle of promise and power

Tight as a schoolgirl’s braids.

And the Jews,

Bearing rifles and regulations

Dove deeper into history,

Brutal, fickle history,

Afraid

And unafraid.

RABBI DAVID WOLPE is the Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.