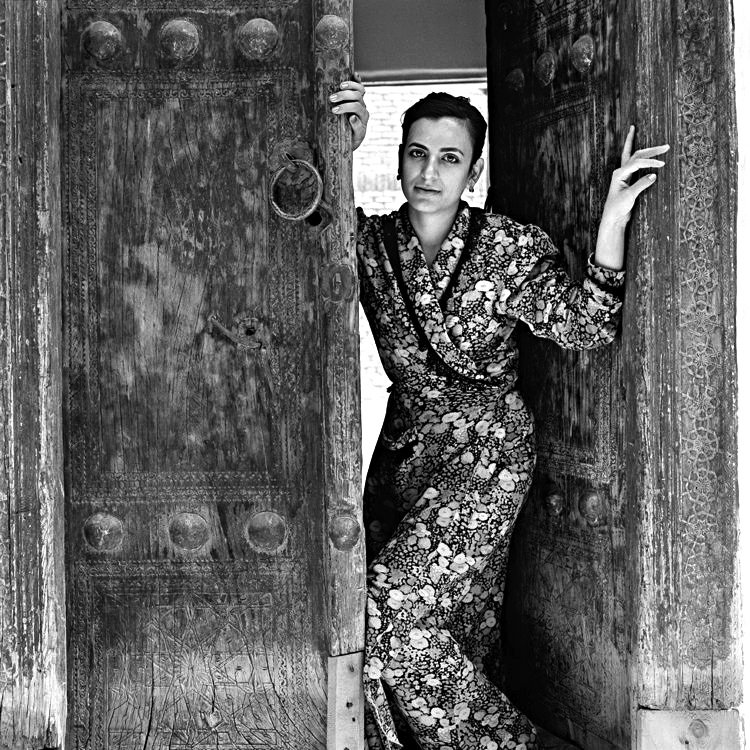

Chrystie Sherman.

Chrystie Sherman. In 2007, while working on a Jewish-themed photography project in India, New York-based photographer Chrystie Sherman decided to travel from Delhi to Kabul to photograph the last living Jew in Afghanistan.

Getting there, however, was tricky. Since 2001, the United States had been at war with Afghanistan, and many parts of the country were still dangerous. Sherman took great precautions in arranging the trip, first tracking down an NPR journalist working in Kabul who could advise her on travel plans and facilitate local connections. Then she hired a fixer who could help her navigate a city in which bombings still rocked civilian life on a regular basis.

When Sherman finally arrived in Kabul, Zabolon Simantov, Afghanistan’s best-known and only remaining Jewish resident, kept her waiting for three days.

“As it turned out, all I needed to do was just show up with the two bottles of promised scotch that I smuggled in for him at great risk, to get into the synagogue on Flower Street called the ‘Jewish Mosque,’ ” Sherman wrote in an unpublished reflection she shared with the Journal.

Since Afghanistan is a strict Muslim country that adheres to Sharia law, it is illegal for most Afghans to possess or consume alcohol (drinkers can be fined, imprisoned or lashed), but foreigners are permitted to import two bottles. When Sherman arrived at Simantov’s modest one-room apartment located on the second floor of the synagogue, she noticed she wasn’t the only one who had brought outside offerings. An open box of Manischewitz matzo also sat on the table. Simantov, she wrote, had become a “cause celebre” — a one-man tourist attraction and living relic of history who offered to tell the story of his Jewish experience in exchange for gifts.

“I started realizing that no matter where I would go, I’d run up against the same problem, which is that these communities are small and disappearing. I began to think of my work as saving the memory of Jewish life through photography.” — Chrystie Sherman

At the end of their meeting, Sherman offered a donation to the synagogue, which had been ruined since the Taliban had ransacked it years earlier. “It looked like a bombed-out bunker,” she wrote in her reflection. The militant Islamist group also had stolen most of the synagogue’s valuable Judaica. So when Sherman offered Simantov a crisp $100 bill, she thought he’d be pleased. But instead, he grew angry and threw the money on the ground. “He said, ‘I want $1,000,’ ” Sherman recounted in an interview. When she didn’t comply, she said Simantov declared the photoshoot over. “And then he locked himself in his room.”

This tense encounter offers a privileged view of the psychic toll that living in a disappearing community can have on its residents. It’s a subject Sherman knows well, having spent the past 16 years traveling the world to document what is left of once-thriving Jewish communities from the Caribbean to North Africa to Central Asia. Her resulting gallery, “Home in Another Place” is a collection of nearly 300 portraits that capture everyday life in Jewish communities least touched by globalization, where life is still lived in small towns and cities, agrarian suburbs and old, decaying buildings.

The last Holocaust survivor in Rhodes, Greece.

Since 2002, Sherman has focused her lens on what she describes as “overlooked” Jewish communities in nearly a dozen countries, including Uzbekistan, India, Greece, Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco and Cuba, many of whose residents trace their roots into ancient Babylonia and Persia, and whose personal histories of persecution mirror the global story of Jewish exile in the Diaspora. Sherman’s work has been exhibited in New York, Rome, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., and she is at work on a book that was waitlisted at the prestigious German publishing house Steidl.

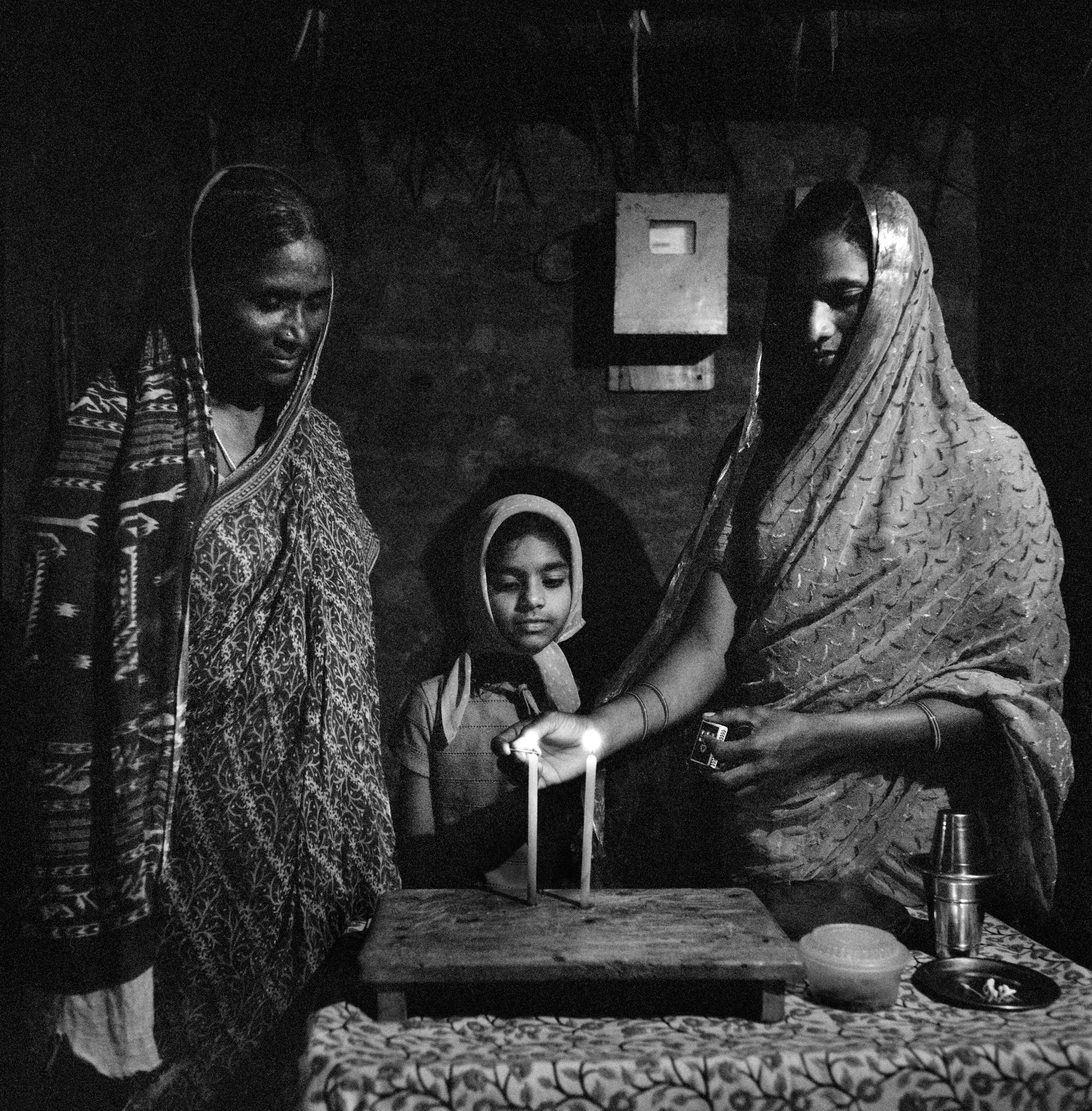

The subtext of Sherman’s portraits is painful: Not one of these communities is growing, but they are surviving, and Sherman’s photographs suggest that the secret behind their survival is at least, in part, a stubborn drive to cling to tradition: It is a family lighting candles together in Kottareddipalem, India; or a minyan of men wrapped in tallitot in Tashkent, Uzbekistan; or young boys wearing kippot in Berdychiv, Ukraine. Though many of these communities have faced varying degrees of discrimination and poverty, and today face the threat of emigration of their young, survival, we learn from Sherman’s portraits, is about maintaining tradition even in the face of extinction.

“I’ve always been interested in people,” the 60-something Sherman said during a recent phone interview from New York. “I’ve always been interested in where they came from, what are they doing now and where are they going.”

But “Home in Another Place” is tied more to her own Jewish journey than her interest in exploring those of others. Raised in a secular household, Sherman decided to deepen her Jewish connection as an adult and in the 1990s joined the Society for the Advancement of Judaism on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. When the synagogue received a grant for projects that explored Judaism through art, Sherman became inspired. She decided to self-fund a photography trip to Ukraine, where her great-grandfather was born, and arranged to spend three weeks driving through “every little shtetl between Odessa and Kiev.”

“All along the way, we’d stop and I’d take portraits of the people I met,” she said.

“I couldn’t believe my chutzpah.”

A family ushers in Shabbat in Kottareddipalem, India.

Sherman also interviewed her subjects about their past. “There’s so much Jewish history in the former Soviet Union,” she said. “There were so many pogroms, all the way up through the Second World War. And then most of the community was killed off between 1941 and 1943 when the Germans arrived. So you felt a huge amount of sadness knowing what had happened in the country and what these Jews had to do to survive.”

When she got home and looked at her contact sheets, she was surprised by the results. “I had never taken portraits before, and I thought, ‘This could be something I could build on.’ So the following year, I went to Central Asia; the year after that, I went to India. I just kept going and going. I became obsessed.”

In Uzbekistan, Sherman encountered a small community of Bukharan Jews — a Mizrahi group from Central Asia — who were once populous but whose numbers in Uzbekistan have dwindled to 150. “I said [to the locals], ‘Where did they go?’ Sherman said. “They answered, ‘Queens, New York.’ ” (Some estimates suggest that around 50,000 Bukharan Jews live in Queens, while more than 100,000 have emigrated to Israel.)

“All of a sudden, I was confronted with this dilemma,” Sherman said. “You’ve got this country that has a really rich history and a really rich culture, and it’s like, not there anymore. What I was doing took on a totally different meaning, because I started realizing that no matter where I would go, I’d run up against the same problem, which is that these communities are small and disappearing. I began to think of my work as saving the memory of Jewish life through photography.”

Sherman was born in Chicago to secular parents who provided little exposure to Judaism. The only times Sherman ever went to shul was with her grandmother. She took her first photographs in high school, after her father gave her a Pentax camera and she followed a Gypsy woman around as she wandered the streets. After graduating from the University of Vermont, she had a brief spell in California working at Universal Studios before moving back East to attend a graduate filmmaking program at New York University.

In the 1980s and ’90s, Sherman built her career as a photo assistant at the Jim Henson Co., a photojournalist with the Associated Press, and a set photographer for “Sesame Street.” When the AP offered her the opportunity to choose her own assignments, she gravitated toward Jewish subjects. One year, she went to Brooklyn right before Passover to photograph Chasidim making shmurah matzo.

The contrast between the vibrancy of Jewish life in America and the vanishing Jewish communities Sherman encountered in her travels has only emboldened her mission. In addition to her portraiture, she is working on the Diarna Project (“our home” in Judeo-Arabic), which aims to preserve relics of Jewish history, such as cemeteries and synagogues through “digital mapping” in video and photography.

“It feels like everything is disappearing,” Sherman said. “Traditional societies around the world are vanishing. Something precious is being lost.”

Sherman’s personal connection to her subject matter emerges in her portraits, which evoke a raw, emotional realism. It’s as if her subjects know that they’re fighting against the inevitability of time and history, standing as the last living monuments of a bygone age. “I think they all realize what’s going on and they’re very saddened by it,” Sherman said of the communities she visited. “It was good when everybody was together; generations of Jews living in one place, eating together and praying together.”

Sherman doesn’t date her photographs, she said, because she wants them to stand as testaments of timelessness. Even though the physical communities may decline and fade away, there is something eternal in the way they lived their lives.

“Synagogue on Shabbat,” Sherman said, noting the one practice that united all of the communities she visited. “That’s the common denominator.”

Sherman said that wherever she went, despite the hardships, she encountered communities stubborn in their refusal to succumb to despair.

“The name of my project used to be called ‘Lost Futures,’ ”she said. “But several communities had a problem with that title. There may not be a lot of these Jews left, but they want to stay where they are and continue to preserve their community. They don’t want to be called a ‘Lost Future.’ ”

You can see some of Sherman’s “Home in Another Place” portraits at chrystiesherman.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.