How does an irreligious Jew find consolation at a religious service?

Seeking such consolation, I attended the Hillel at UCLA High Holy Days services conducted by Rabbi Chaim Seidler-Feller. I don’t often go to services, but in February our oldest daughter, Robin, died, and I felt drawn there.

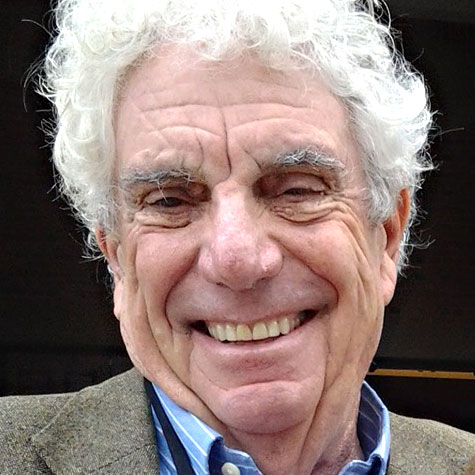

Rabbi Seidler-Feller — people simply call him Chaim — is a comforting presence, at least to me. I have attended a few High Holy Days services at UCLA Hillel in the past and have interviewed the rabbi for my column in the Jewish Journal. He has a scholarly yet freewheeling mind, an ability to explain our religion to skeptics like me and to welcome us into the flock, even for a brief time. He has an understated sense of humor that appeals to me, and he is a warm and approachable man.

I went alone on Rosh Hashanah. Nancy, my wife, is an abstainer. My late father once asked her why she didn’t go to temple. “Dad,” she said, “I don’t believe in it.”

“Believe in it,” he replied. “Why, nobody believes in it.” In his mind, it was simply his duty to go.

As the services went on around me, I was thinking of Robin. Images of our family life flashed through my mind, mostly the good times we had, but also the tough ones experienced by Robin, her sister, Jennifer, Nancy and me, a mental slide show of the Boyarsky family story.

Another family — a dysfunctional one — was the subject of the Torah reading and of Rabbi Seidler-Feller’s words to the congregation. It was the family headed by Abraham, including his wife, Sarah, and her maid, Hagar. As is well known, Sarah, unable to conceive, persuaded Abraham to father a child with Hagar, who gave birth to a boy named Ishmael. After his birth, Sarah conceived and gave birth to Isaac. The two mothers did not get along. Sarah, feeling Ishmael was a bad influence on Isaac, persuaded Abraham to send mother and son away. He complied, but after their banishment, they had a harrowing experience in the desert until an angel of God appeared to save them. God promised that Ishmael would lead a great nation. Isaac, too, was chosen to lead a great nation, and the conflict continues to this day: Isaac’s Jews versus Ishmael’s Arabs.

Rabbi Seidler-Feller, I am sure, had told this story and commented on it countless times. Yet, in his telling, it was fresh, dealing as it does with the insoluble issues of relationships with God, with husbands, wives, siblings and, as it eventually turned out, among Arabs and Jews, although the rabbi did not dwell on this point.

With so many angles of the story to consider, I lost myself thinking about it, not paying much attention to the service. What was wrong with Abraham? How could he kick out Hagar? Of course, what could you expect from a man who later was about to sacrifice Isaac on God’s command until God rescinded the terrible order? I wondered how that defense — God told me to do it — would stand up in a trial in the Criminal Courts Building.

In early afternoon, we approached the time for the recitation of the Mourner’s Kaddish, and my thoughts returned to Robin. By the time of the prayer, the congregation had thinned out. I looked around at others saying the Kaddish, wondering whom they had lost, what they were thinking about and whether they were as sad as me. Not entirely sad, however. I smiled, thinking of how the witty Robin, although appreciating the fact that she was loved and being remembered, would have had some ironic comments about the event.

On Yom Kippur, I again went to services at Hillel, this time with my cousin Rhona Singer. She is as irreligious as me. We enjoy going together, because it brings back memories of growing up in Oakland with our large family and of old friends and religious school at Temple Beth Abraham, where my mother was the principal.

I understand the solemnity of the day, but I find it difficult to repent for the many sins listed in the Al Chet recited by the congregation, even though Rabbi Seidler-Feller explained it didn’t mean we had committed them all. We were repenting for Jewish community members who had committed them.

One sin always stops me — “For the sin which we have committed before You by scoffing.” Scoffing is what I have done for a living throughout my career. Scoffing is central to my character. I couldn’t very well repent that.

During the Yizkor service, Robin’s name was among those recited by the rabbi. Rhona touched my arm in sympathy.

I left Hillel consoled, helped by a rabbi who makes a place for the religious and the scoffers. Feeling welcome there, I was free to let my mind roam through thoughts of family, including the daughter we’ve lost. Over the years, we’ve had more happy moments than sad, and I’m thankful for that.

Bill Boyarsky is a columnist for the Jewish Journal, Truthdig and L.A. Observed, and the author of “Inventing L.A.: The Chandlers and Their Times” (Angel City Press).

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.