When the top editor of the world’s newspaper of record flips and flops and flips again on a subject as sensitive as use of the N-word, you know things are getting messy at The New York Times. And when a Pulitzer prize-winning columnist claims that the paper “spiked” his column on the subject, well, it just gets messier.

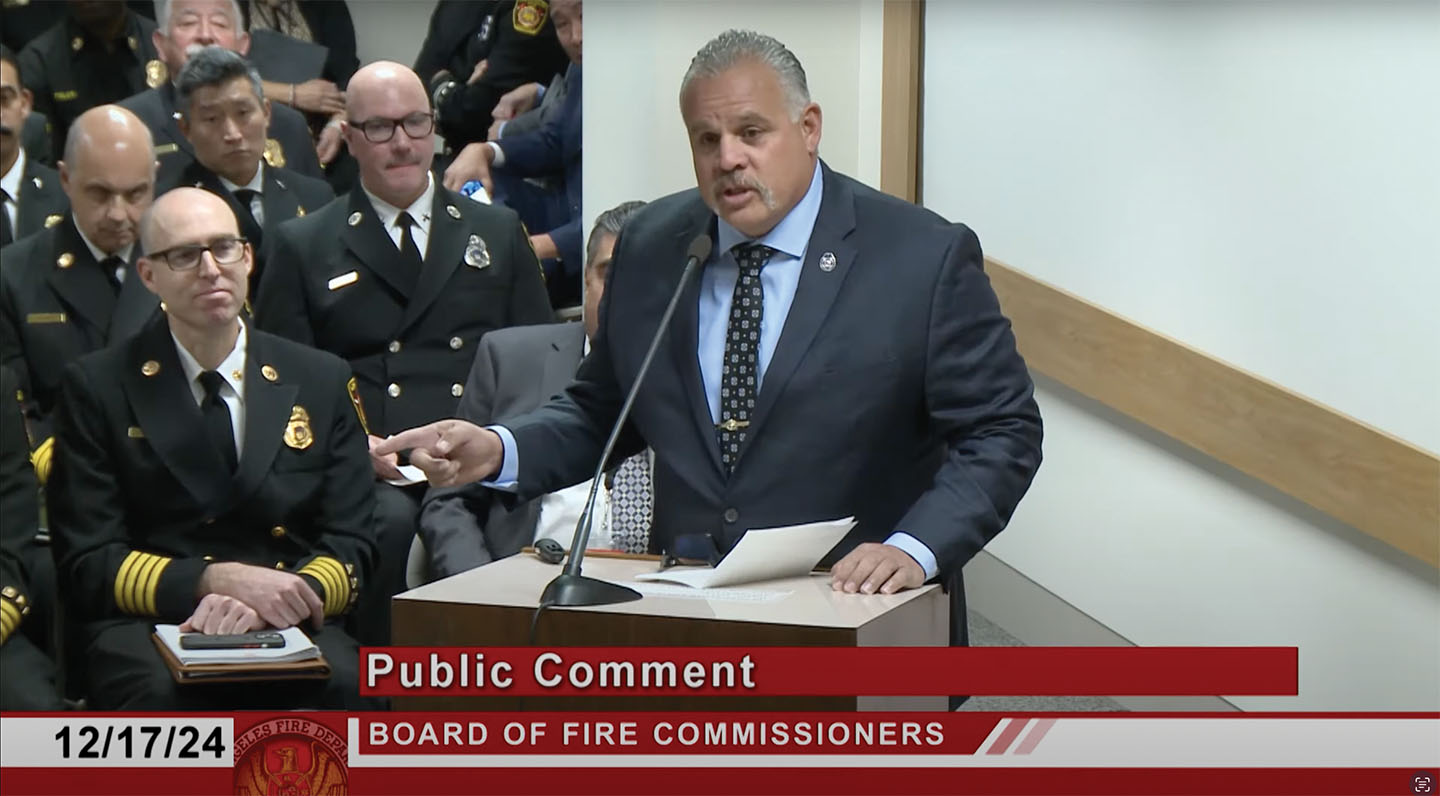

This sad story started when longtime New York Times science reporter Donald McNeil was accused in 2019 of using a racial slur while on an overseas trip chaperoning high-school students. At the time, the paper reprimanded but chose not to fire him because there was no malicious intent: McNeil allegedly was referring to the N-word as part of a debate, not using it as a slur. So editor-in-chief Dean Baquet gave him a “second chance.”

But when the story resurfaced last week in The Daily Beast, an internal firestorm erupted at the Times, with 150 outraged employees writing a joint letter to management saying that “intent is irrelevant” and demanding an apology and further investigation.

After McNeil apologized and then was forced to resign, Baquet changed his tune on intent and declared: “We do not tolerate racist language regardless of intent.”

This triggered yet another firestorm for the simple reason that it’s hard to justify the notion that “intent” shouldn’t matter. Liberal columnist Jonathan Chait explained that distinction in New York Magazine in a piece titled, “Describing a Slur is Not the Same as Using it.”

That is so self-evident that Baquet himself flip-flopped yet again this morning by acknowledging in a staff meeting: “Of course intent matters when we’re talking about language in journalism. Intent matters.”

Maybe he was influenced by the cancelled Bret Stephens column, which, according to reports, began as follows:

“Every serious moral philosophy, every decent legal system, and every ethical organization cares deeply about intention. It is the difference between murder and manslaughter. It is an aggravating or extenuating factor in judicial settings. It is a cardinal consideration in pardons (or at least it was until Donald Trump got in on the act). It’s an elementary aspect of parenting, friendship, courtship and marriage.”

The columnist added: “A hallmark of injustice is indifference to intention.”

What I find especially noteworthy about this brouhaha is how tedious it is. Does a Pulitzer prize winner really need to invest a whole column on an idea as obvious as the value of intent?

But this is The New York Times, so it’s hard to look away. The drama of a top editor who gets an obvious thing right the first time, but then panics when bullied by a mob, and then panics again and redresses himself, is endemic of how low and fearful our discourse has become.

In a cancel culture run amok, one of the biggest fears in America today is the fear of saying the wrong thing. I can understand that impulse if the “wrong thing” is insulting someone because of their race, religion, gender, ethnicity or otherwise. I’d love to live in a world where people are extra careful before unleashing such insults, even as I appreciate that the insults are generally protected by the laws of free speech.

In a cancel culture run amok, one of the biggest fears in America today is the fear of saying the wrong thing.

But when we become afraid to even mention a word to describe something, when we’re petrified that the cancel mob will come after us and our livelihood, I’d say we’re due for a sober reckoning, or at least some candid analysis.

As Columbia linguistics professor and author John McWhorter wrote on Substack, “My own observation of this sort of thing… is that the people hunting down McNeil are swelling with a certain pride in claiming that ‘We decide what we will tolerate,’ as if this constitutes what black nationalists would term ‘self-determination.’ But the issue is whether what is being determined for the self is good for the self in question.”

McWhorter, who is Black and has written often on these issues, adds that “it is only a certain mob who are making this ‘determination’ [and that] the idea that it is inherent to black American culture to fly to pieces at hearing the N-word used in reference is implausible at best, and slanderous at worst.”

The more important point, he writes, is that “insisting on this taboo makes it look like black people are numb to the difference between usage and reference, vague on the notion of meta, given to overgeneralization rather than to making distinctions.”

It would be useful to see more reporting and courageous commentary on this subject. New taboos that are silencing people through fear of losing their jobs is not just a “problem” — it is an alarming trend and condition that must be exposed through maximum sunlight.

And speaking of exposure, I would hope the Times will flip-flop yet again and decide to publish Stephens’s column. Even a meltdown can use some sunlight.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.