In a zero-sum game, no one can win without someone else losing. It’s like grading on a strict curve with a predetermined allocation of As, Bs, and Cs. Students can put in long hours studying together, thereby improving the overall quality of their performance, but a particular student can only benefit at the expense of another.

Is that how the world works? Are we pitted against each other with no possible gain from acting collectively?

That is where game theory comes in. For many years I taught the “Prisoner’s Dilemma” in my economics classes. Two people rob a bank and appear to get away with it. The police know they did it, but they don’t have sufficient evidence to convict them unless one of the robbers confesses. So they are placed in separate cells, and each is presented a plea bargain deal: If you confess, you will get a one year sentence. But if you don’t, and the robber in the other cell accepts the offer, your sentence goes up to five years. Being risk averse, most would take the plea bargain, since one year in jail is a lot more palatable than the possibility of five. But if the robbers trust each other and keep quiet, they avoid prison altogether. If you think it is a bit strange that economists illustrate the benefits of acting in consort with an example of how guilty parties can evade the law, well, that’s economics for you!

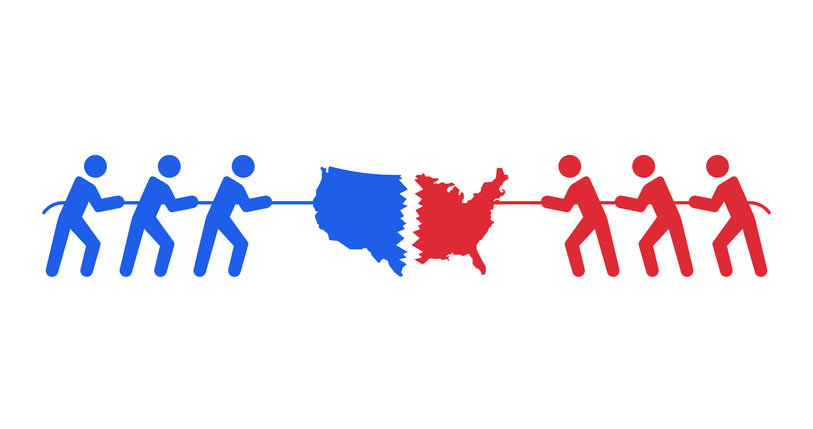

While the idea that we can all gain from cooperation has been demonstrated throughout history, it seems to have been lost amidst the rancor of recent years.

Politicians are so partisan that, in classic zero-sum game fashion, they would rather scuttle legislation that is in the nation’s best interest than to share credit with their opponents. Republicans rejected an immigration bill they helped write because they didn’t want the Democrats to look good; Democrats are so eager to raise corporate taxes in an effort to repudiate the former president that they dismiss the likely negative impact on economic growth. Members of both parties seem to agree on only one thing: Global cooperation is somehow bad, and tariffs are effective, ignoring centuries of evidence to the contrary. Neither extreme partisanship nor isolationism promotes the greater good.

Politicians are so partisan that, in classic zero-sum game fashion, they would rather scuttle legislation that is in the nation’s best interest than to share credit with their opponents.

That brings us to the Middle East. A decade ago, Professor Gary Saul Morson and I edited a volume titled “The Fabulous Future? America and the World in 2040.” We asked experts across a variety of disciplines to predict where the world was going. The chapter on international politics was written by Robert Gallucci, former dean of Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, and the chief negotiator with North Korea under President Clinton. He focused on “black swans,” improbable events that have the potential to change the course of history. One of them was massive casualties resulting from a future pandemic reminiscent of the Spanish Flu. He unfortunately nailed that “swan.”

On a much more promising note, another of Gallucci’s “swans” was the successful resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, opening the door to key Arab states acknowledging Israel’s right to exist.

Recall that a mere 10 months ago we were excitedly traveling down that road until any hope of extending the Abraham Accords was abruptly dashed by terrorists desperate to undermine the peace process. But picture for a moment a world without Hamas, where we can once again envision longtime adversaries becoming partners. There is little doubt that enhanced regional trade, and the reallocation of resources away from military spending, would benefit all involved. And history suggests that the stronger the economic links between nations, the less likely they are to engage in hostilities.

The biggest nightmare for Hamas, and the mob that supports them, is a solution that brings enduring peace to the region and security to Israel. That would be a true positive-sum game, with the world better off.

This dream remains achievable today. When we successfully conclude this agonizing war, it will be time to lose our zero-sum mentality. Only then can our most heartfelt prayers be answered.

Morton Schapiro is the former president of Williams College and Northwestern University. His most recent book (with Gary Saul Morson) is “Minds Wide Shut: How the New Fundamentalisms Divide Us.”