When I read initially that the Houthis had launched a deadly drone attack against Tel Aviv, I had two immediate thoughts: First, what unspeakable evil and foolishness that Yemen, the poorest country in the Middle East, where 80% of the population is currently starving, is choosing to spend precious funds on drones and bombs to attack Israel (though Iran is paying the Houthis to carry out the attacks). My second thought focused on a specific segment of Israelis: What must Israel’s Yemeni population be thinking right about now?

I may be Iranian American, but I identify deeply with Israeli Yemenis, and anyone else in Israel whose family escaped an oppressive country. Whether in Los Angeles or Tel Aviv, we’re a unique bunch, one that most Westerners cannot understand: I’m specifically referring to people who are so ashamed of the country from which they escaped — a country that is now targeting them.

The Iranian revolution that turned the country into a fanatic theocracy and major violator of human rights occurred 45 years ago, before I was born. In those decades, I’ve experienced my fair share of embarrassment and shame over the terror unleashed by my country of birth. But that was nothing compared to the horrifying shame I felt after learning that Iran had helped Hamas plan the Oct. 7 massacre. I was inconsolable over the particular injustice that Iranian Israeli victims of Oct. 7 were targeted by the very regime they and their families thought they had escaped.

Again, most Westerners have a hard time grasping this reality. If an American travels to Europe today, he or she may meet locals at a pub and sigh with exasperation over the circus of American politics at this historically heated moment. Conversely, a Frenchman may visit the United States today and shake his head over the consequences of disastrous immigration policies in his home country.

But exiles from regions such as the Middle East are a whole other matter: The last time I visited Israel, I informed the locals that I was born in Iran, then proceeded to apologize for everything the country had done since 1979. It’s one thing to admit that your home country has flaws; it’s another to know that your former country is the world’s number one state sponsor of terror.

It’s a strange, ambivalent reality: On the one hand, whether Iranian or Yemeni or Syrian Jews, we know that tyrannical (and antisemitic) regimes do not represent us. But in other ways, seemingly wherever we go, we are still seen as de facto ambassadors of a country we and our ancestors called home for thousands of years. To the world, we are, in effect, reluctant ambassadors of countries that have chased us away.

It was no surprise, then, that immediately after the Tel Aviv attack, social media users arrived in Tel Aviv’s Yemeni neighborhood of Kerem HaTeimanim (the name means “Vineyard of the Yemenis”) to ask people what they thought of Yemen, and of the Houthis. Kerem HaTeimanim is adjacent to the famous Carmel Market, and many Yemeni Jews, some of whom must have been second generation Israelis, were asked if they had a message for the Houthis back in Yemen. The responses, all in Hebrew, were quintessentially Israeli:

It was no surprise that immediately after the Tel Aviv attack, social media users arrived in Tel Aviv’s Yemeni neighborhood of Kerem HaTeimanim to ask people what they thought of Yemen, and of the Houthis.

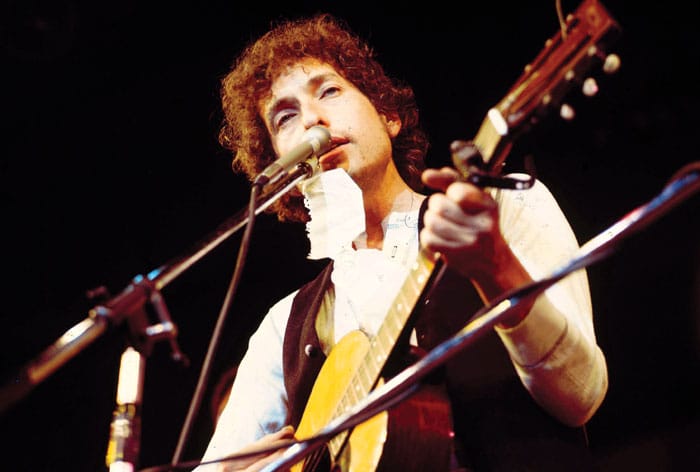

“You’re Yemeni, right?” a young woman who was filming the video asked a kippah-clad, gray-bearded man as he prepared traditional Yemeni flatbreads, most likely at a stall at the Carmel Market. “I’m Swedish,” he answered jokingly. His response reminded me of each time that Americans asked me or some of my Iranian friends from where we hailed, and we responded that we were Italian.

“Do you have a message for the Houthis?” the young interviewer asked the man. “A message for the Houthis?” he repeated the question. “Go to hell.” When asked if the Houthis scared him, the man, who was holding a large tray of flatbreads ready to be baked, answered, “Can anyone scare Am Israel (the people of Israel)? No one can scare Am Israel!”

Two dark-haired young men of Yemeni descent sat at a cafe and stated, “A few Houthis won’t affect us. Definitely not here in the Yemeni neighborhood. It’s the stronghold.” Every now and then, that’s exactly how I feel when I read dire headlines about Iran while living in an area of West L.A. called “Tehrangeles.”

There were so many memorable responses, and I want to share even more of them with readers:

“They’re backwards,” said one Yemeni woman regarding the Houthis. “I think they’re overdoing it,” a tan, dark-haired man working at another food stall said “I love Yemenis,” added his co-worker. “But you went too far, friends. In Tel Aviv, and with no warning!” he chuckled.

My favorite respondent was a buff, young Yemeni baker with a bald head, a heavily tattoed upper arm and an impressive black goatee and mustache. While calmly continuing to pull at a giant, pliable mass of dough, he yelled, “Why at four in the morning?!” (regarding the bombing). “Do it in the afternoon! Why at four?!”

“Congratulations to the Houthis,” said another young man. “Everyone from Hamas to Iran has tried to hit Tel Aviv and failed. And they [Houthis], suddenly with their flip flops, opened up a new parking spot for us.”

Finally, there was a young Yemeni man who looked straight at the camera and delivered his own message to the Houthis, “I’m sure our Jachnun [bread] is better than yours, you #%S!!”

The responses of these Israeli Yemenis say it all: Embarrassment and dissociation on the one hand (one woman said, “They’re embarrassing the Yemenis! We’re not connected to them at all”), and pride and ownership in their own Yemeni identities, on the other. It’s almost as if they were saying, “We’re Yemeni too, but unlike you [Houthis], we got it right.” Millions of Iranians feel the same way about the regime in Tehran.

The attack against Tel Aviv was no laughing matter; a man was killed and the bomb struck an emotional blow to residents of the city who may have thought they were untouchable. But in the city’s Kerem HaTeimanim neighborhood, at least, there were some who responded with lightness, mockery and yes, even laughter. In fact, it seemed like they had no choice. That’s probably because unlike other Tel Aviv residents, some of these Yemeni Jews had stared the devil in the eye and knew exactly with whom they were dealing.

Few nations throughout history have been kind to Jews. That’s why I sometimes envy Moroccan Jews. The Judaism they knew (and continue to know) is the “Judaism of the sun,” as Jewish Journal editor-in-chief David Suissa, who was born near Casablanca, once wrote.

Theirs was “a Judaism inspired by mystical deserts and cozy neighborhoods,” in a land where kings have generally been good to Jews, and treaties of peace and recognition with Israel have been formally signed.

Still, I do my best to remember that my own Persian identity is rife with thousands of years of progress, light and civilization, namely during the Persian empire, beginning with Cyrus the Great, whose exceptional rule formally recognized human rights, as well as during the mid-twentieth century — a golden age of sorts for Iranian Jewry.

Despite a history-altering Arab conquest of Persia 1,400 years ago, we have managed to retain most of our own language, music, food, culture, literature and most importantly, a magic combination of secularism and spirituality. Given Iran’s current theocracy, that’s ironic, because most Persians seem to prefer a distinct separation between religion and the state.

The Houthi attack has reminded me that I wish more Israelis whose families hail from Arab and Muslim countries were asked how they feel about Israel’s enemies. Their voices are vital. And their lack of presence in the countries they once called home have resulted in nothing but havoc and devolution in their former countries.

I asked a friend who lives in Tel Aviv, but whose parents were both born in Yemen, what he thought about the fact that the country his family called home for thousands of years is now overtly attacking the only country he has ever called home: “Let me put it this way,” he said, “Either we’re the real Yemenis, because we actually care about life and focus on progress. Or they are the real Yemenis, and they are actually showing their true values. And if it’s the second case, we no longer want anything to do with that country.”

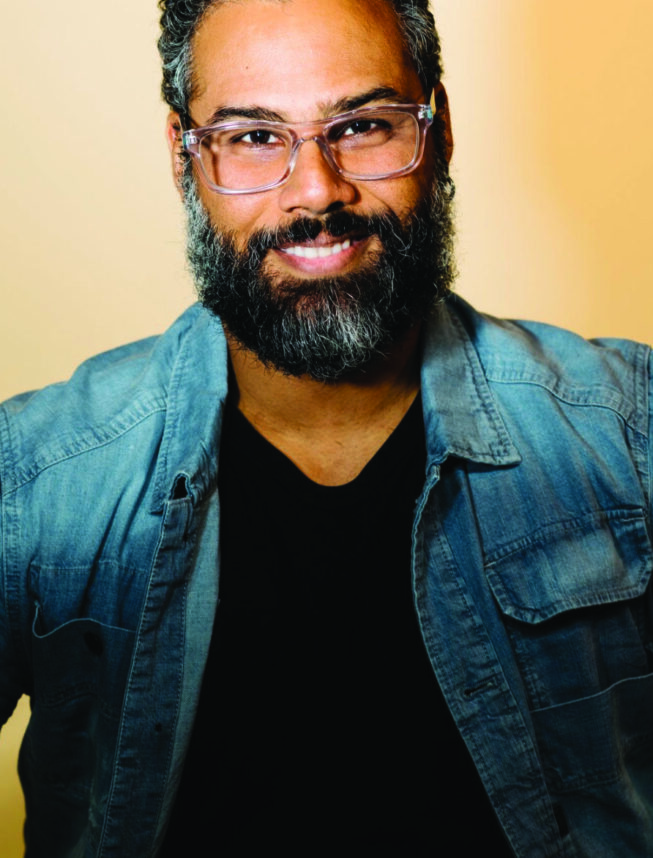

Tabby Refael is an award-winning writer, speaker and weekly columnist for The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Follow her on X and Instagram @TabbyRefael.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.