If I had a nickel for every time readers said they enjoyed various mentions of my mother in my weekly column, I would have several dollars. If you do the math, that’s a lot of praise for my mother — all deserved.

But I haven’t devoted equal column space to my father, perhaps because he’s often outshined by my mother. Yet, more than anyone else, my father has shaped my life and made me who I am.

I still remember sleeping on his chest as he lay on the couch back in our house in Tehran and listened to his beloved Kol Israel (“Voice of Israel”) Persian-language radio broadcasts. I’ll never forget huddling in my father’s arms as he held a transistor radio that warned of imminent Iraqi air raids in our neighborhood during the Iran-Iraq War. Or dozing off on his chest again at our apartment in Los Angeles, calmly waiting for Shabbat dinner to start, as the “TGIF” weekly television lineup filled our living room with English-language dialogue.

Come to think of it, something was always playing in the background in my mother and father’s home.

It’s time to complement “An Interview with My Iranian Mother,” which I wrote in January 2022, with an interview with my Iranian father, who requested that I only use his nickname, Heshy. Like nearly every Iranian father in exile, my dad believes that the regime is tracking his every move. I should note that his concern about Iranian surveillance isn’t easily-dismissible paranoia; in recent years, the FBI has repeatedly arrested individuals on charges of spying on behalf of Iran and conducting surveillance of Jewish communities.

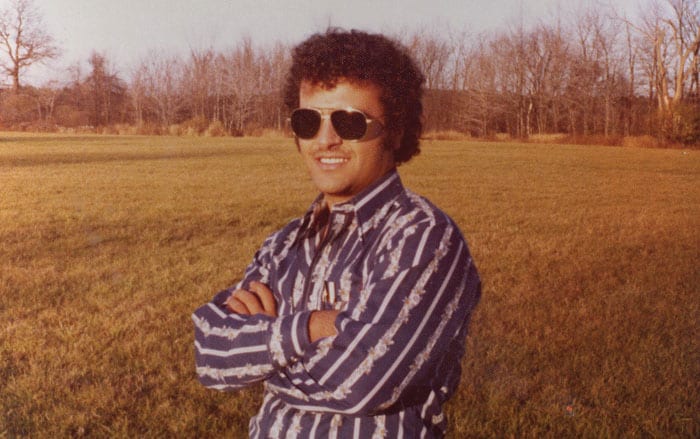

Think of him as a loving, dark-skinned teddy bear who always knows to pick the best pineapples, and who saved my life and those of future generations through his intelligence, resilience and sacrifice.

But back to an interview with my father, who, moving forward, will be referred to as “FH” (Father Heshy). Think of him as a loving, dark-skinned teddy bear who always knows to pick the best pineapples, and who saved my life and those of future generations through his intelligence, resilience and sacrifice. The following interview was conducted in Persian.

Tabby Refael: Hi, Baba.

Father Heshy: Hi, Joojoo (“baby bird” in Persian).

TR: I’m calling to interview you.

FH: I need more time! I want to be well-prepared for our interview.

TR: That’s very sweet. Are you sure now isn’t a good time?

FH: Alright, if you really want to know, I have to take your mother to the doctor. Then to the market. Then to Smart and Final.

TR: But Smart and Final is a supermarket.

FH: I know. But she only likes the cottage cheese at Pavilion’s.

TR: G-d bless you, dad. I’ll call you back.

A few hours later, my father arrived at my home with a small notebook, in which he had written everything about his life that he wanted to discuss during our interview.

TR: Hi, Baba.

FH: Hi, Joojoo.

TR: What are some of the thoughts you wrote in your notebook?

FH: Just important events about my life, in a nutshell. I’ve always wanted the best for people. See here? I wrote about my first job.

TR: Tell me about that.

FH: I was 15. I worked in a Tehran barber shop. Then, I worked for a company that distributed medicine wholesale. Concurrently, I took night classes. A client was so impressed by how fast I used an abacus that he offered me a job. He asked me how much I wanted to be paid.

TR: An abacus! What did you say?

FH: I was so plucky. I said I wanted three times more than I was making. And he said, “You’re hired.”

TR: Did you learn any important lessons from those early jobs before you became a chemist?

FH: I realized I could make myself proud. At my new job, I met highly-educated people for the first time. “Why can’t I be like them?” I asked myself. So I applied to college in America. When I returned to Iran before the revolution, I helped my parents buy a house. It cost 25,000 toman.

TR: How did it feel to be able to give back to your parents?

FH: I loved taking care of them. I took them to the doctor. There used to be a restaurant called Kolah Farangi in Tehran. I used to take them there a lot.

TR: How did grandma and grandpa respond to your news about going to America for college?

FH: At the time, I was the only one in the whole family to pursue higher education, and that was a big deal. But I’ll never forget when I was leaving. A song played on the radio that went something like, “Oh, caravan, remember to go slower, because you’re taking away the comfort of my soul.” My mother turned to me and told me, “So you’re really going?” I said, “Yes.” She sighed and responded, “You’re leaving me for the States and taking the comfort of my soul.”

I said, “Mom, I understand, but I have to make a life for myself.” In hindsight, I wish I’d been more sensitive.

TR: That was the first time you told grandma you were going to America, but that time, you came back. The second time occurred when you decided to escape Iran with mom, my sister and me. What was grandma’s reaction the second time?

FH: The second time, she understood that we needed to leave. But she also understood that, in their old age, she and your grandfather had to stay. My poor mother. Years later, one of our relatives visited her in Tehran, then came to the U.S. and told me, “I saw your mother. You should visit her again.” I told our relative there was no way I could return. Then he told me that my mother had said, “Just tell Heshy I want to see his face one more time. Then, I can go [pass away].”

At this point, my seemingly unbreakable father teared up, and I fell into his arms as I sobbed and contemplated everything we lost, and the loved ones whom we never saw again.

TR: What are your feelings toward America, Dad?

FH: I love America. I got my wish — to study here. The first time I came [for college in the mid-1970s], I heard a rabbi speaking on a radio program. I was bewildered.

TR: What did that tell you about America?

FH: It meant there was freedom of expression here. It also meant that Jews could live comfortably. I had never heard a rabbi talk on Iranian radio.

TR: Do you still consider Iran your homeland?

FH: I’d love to go back to where we lived, in the mountains of Tehran, where I used to take my dad and make chicken kabob over a portable grill. I derived so much joy from his enjoyment.

TR: What does Israel mean to you?

FH: Nothing. Nothing. There are spies all over here. Don’t ask me about Israel!

TR: What do you wake up for in the morning?

FH: My family. And maybe for exercise, studying and communication with people. I like people. You can always learn from them.

TR: Why do Persian dads consume so much news related to the Middle East, then speak about nothing but the news when they see each other at dinner parties?

FH: I’d love to see peace in the world, especially the Middle East. I’m so excited about the Abraham Accords. That was the most intelligent thing I’ve seen in years, to bring peace and understanding, and to get rid of negative stereotypes.

TR: What’s the key to being a good father?

FH: To be respectful and understanding. My father was so kind. He was quiet, but sensitive.

TR: You’re not quiet!

FH: I study anything and everyone. Science, technology, inventions, philosophy and people.

TR: Dad, do you have a best friend?

FH: Well, yes. You. And your sister. My daughters.

Happy Father’s Day to dads everywhere.

Tabby Refael is an award-winning writer, speaker and civic action activist. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @tabbyrefael

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.