We’re only one week into the new year, but I have yet to think of 2021 as simply following a bad year. Calling 2020 a “bad year” is like saying Jeffrey Dahmer had bad eating habits. Dahmer was a cannibal who killed and ate 17 men and boys. Imagine being the sibling who came after him? The bar is set pretty low for an improvement.

That’s what 2021 must feel like, as it follows the most hated year in recent memory.

But many people don’t realize that 2021, however it ends up, will have the difficult task of recalling some other dark and epic events. This year, we’ll mark the anniversaries of three of the most important stories of the twentieth century — stories we’d do well to remember but which younger generations, including mine, have completely pushed to the backburner.

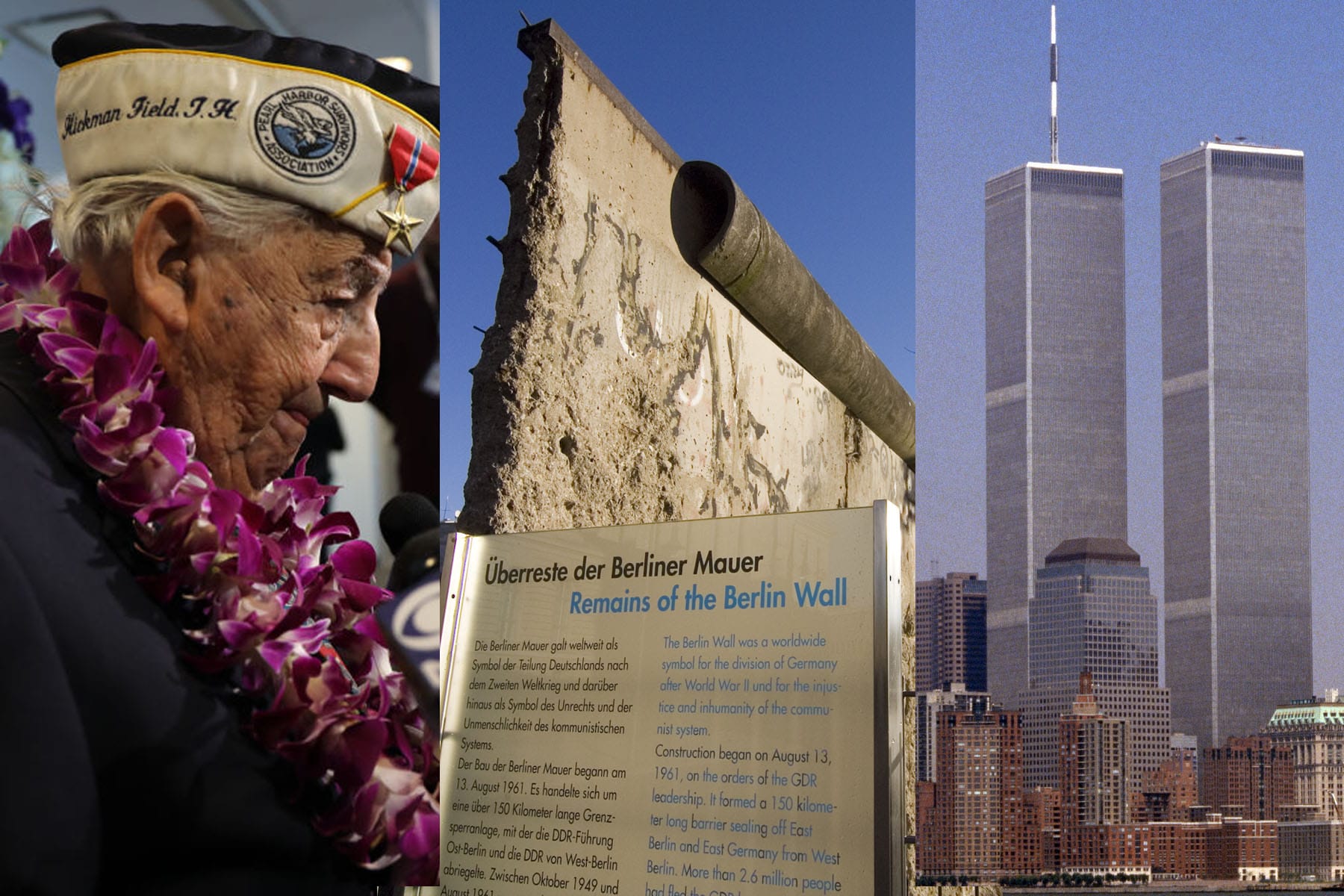

Eighty years ago this year, in December 1941, the United States entered World War II after the Japanese killed 2,403 servicemen and women at Pearl Harbor.

Eighty years. That’s a long time.

That means that some of the youngest American troops to have served in that war are now in their late nineties (the actual youngest soldier was Calvin Graham, who enlisted in the navy at age 12. He died in 1992). Yes, that means that all of the remaining Americans who fought Nazis, liberated starving Jews from death camps and celebrated the triumph of courageous good over cowardly tyranny are now almost 100. All of them.

Most of us who’ve ever shaken hands with a veteran, especially an older veteran, know they’ve been in the presence of someone special. What has this person seen? What does he or she think of me? I’ve always felt a sense of awe upon seeing much older veterans, whether at the bus stop or a museum (in pre-pandemic days). Some of them wear special caps letting us know when and where they served. I always thank them for their service. These veterans remind me of Argentine writer José Narosky, who said, “In war, there are no unwounded soldiers.”

But they’re dying quickly. Soon, there’ll be no World War II veterans left. According to the United States Department of Veteran Affairs, only 325,574 of the 16 million Americans who served in that war are still alive. That means roughly 80% of them are gone.

Here’s some perspective: there were exactly eighty years between the start of the Civil War (in 1861) and when America entered World War II. That means that in 1941, if you were lucky, you’d still be able to speak with a member of the Union Army, though, like today’s WWII veterans, he would have been very, very old. Oh, the questions I would have wanted to ask him.

Of course, the fact that this year marks the eightieth anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor also means that all of the world’s remaining Holocaust survivors also are in their eighties and nineties, but the race-against-time significance of that merits its own series of columns.

How much can we identify today with something that transpired 80 years ago? Before I can even ponder that question, I find myself wondering how much or how little we can relate to something that happened 30 years ago.

This year also marks the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of communism and the disintegration of the former Soviet Union in 1991. This memorialization is where it gets tricky for me. Naturally, I wasn’t alive during World War II, but I did live through the historic downfall of one of the most murderous regimes of the last century.

The only problem? I was nine and remember virtually nothing. In fact, I’m pretty sure that while my parents were watching the television in shock as the Soviet sickle and hammer flag was lowered for the last time, I was in the other room, dancing to “Good Vibrations” by Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch on our big stereo.

I belong to the generation that sort of remembers the tyranny of the USSR, though, I’ll be honest: I personally remember none of it. But that’s only because I was face-to-face with tyranny as a child in post-revolutionary Iran in the 1980s, and there are only so many dictators one can handle. When we came to the United States in 1989, I thought “Gorbachev” was the name of a Russian cocktail.

What does it mean to be among the generation of those in our thirties, for whom the thought of an omnipresent, “evil empire” (what President Ronald Reagan called Russia in 1983) is almost cartoonishly comical and oh-so black and white? It means we dismiss much of the concerns our parents’ generation has over the censorship of words and, yes, even thoughts that are ravaging American society today like fast-spreading mold. It also means millions of younger people are openly and passionately embracing the economic policies of Democratic Socialism and its charismatic leaders in America.

I’m not saying that every young person who voted for Bernie Sanders dismisses the economic and social havoc wreaked by socialism during the past 100 years. And there are plenty of older Americans who identify as Democratic Socialists. But what I am saying is that there isn’t a single 25-year-old champion of Sanders who was even alive when that miserable flag was lowered over the Kremlin in December 1991.

Ever the overachiever (did it have a choice?), 2021 will also mark the anniversary of another milestone in not just American history but also world history itself: This September will mark 20 years since that hideous Tuesday in 2001, when, whether in person or on TV, we watched in horror as two airplanes slammed into the World Trade Center, bringing the very foundations of our American lives to their terrified knees.

I remember that morning. Twenty years later, I remember my exact feelings and inescapable fears. I was two weeks shy of starting college, which means I was old enough to really take everything in. And rather than missing everything by dancing to music in the other room, I was on the kitchen floor, glued to the TV alongside my horrified mother and father. There are some moments in one’s life — moments that occur completely outside of you — whose terror confirms that nothing will ever be the same again.

By contrast, those entering their freshman year of college in 2021 weren’t even alive on September 11, 2001. And most of those graduating this year were only one during the worst terrorist attack on U.S. soil in history.

Their age doesn’t mean they don’t understand what happened that day (or the aftermath of it, which still reverberates today). It just means there’s no frame of reference, no semblance of the feelings — the visceral, fearful, confused, nation-in-mourning feelings — that those of us who still remember that day will never forget. And when it comes to personal identification and collective memory, feelings are everything. (Whether all of this affects the voting habits of younger generations is also best reserved for another column.)

When it comes to personal identification and collective memory, feelings are everything.

If I was one on 9/11, I wonder whether a veteran of Iraq or Afghanistan who served in 2003 would seem as ancient to me as someone who served in the Civil War. In contemplating 9/11, would I feel a sense of personal repulsion at the thought of politicized religious fanaticism? (In truth, I already hold such views as a result of those charming years back in Iran). Would the history of that time fit into the oversimplified and cartoonish categories of “good vs. evil,” of feeling like anyone older than me had been fed a handful of lies about an angelic America versus an “Axis of Evil” (according to President George W. Bush in 2002)?

It’s possible. Many of my friends, who, like me, actually lived through 9/11, still haven’t forgiven Bush and cringe at the thought of another American-led war in the Middle East. Me? I take a more nuanced approach. I study American history, grow wide-eyed from the truth and ask questions about the lies. More than anything, I try to learn from the lies. And I practically wish I could kiss the hand of every American serviceman and woman who fought in the Middle East after 9/11, even if he hated Bush and other American leaders more than he hated Saddam Hussein, or even if she were to look at me like I’m a naive, rosy-eyed simpleton. Maybe that’s precisely what I am.

This December, pandemic lockdowns pending, we’ll gather one way or another to commemorate the eightieth anniversary of Pearl Harbor. Want to contemplate something strange? In September 2081, we (and, I’m assuming, our robot masters) will gather to remember the eightieth anniversary of 9/11. I’ll be 99 years old by then. And if my mental faculties will still be sharp enough to share memories of that ominous day, I’ll speak with anyone who has questions. I just ask that someone hands me a Gorbachev cocktail beforehand.

Tabby Refael is a Los Angeles-based writer, speaker and activist.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.