Over the past several weeks, the nation has been engrossed in a revitalized conversation about race relations in the United States. Not surprisingly, the Jewish community has been an active participant in those discussions and has been working to help chart a path forward.

But the more difficult question is whether such commitment and support should flow in both directions. In other words, as American Jews stand in opposition to racism and march on behalf of racial justice, should we expect — or hope — that members of the country’s most prominent communities of color will stand with us when we face prejudice and intolerance of our own?

When synagogues were attacked in Poway and Pittsburgh, minority voices across the country offered statements of support and comfort as we grieved. For that compassion, we will be forever grateful. But when the focus shifts to matters of public policy, these relationships become more complicated.

In other words, as American Jews stand in opposition to racism and march on behalf of racial justice, should we expect — or hope — that members of the country’s most prominent communities of color will stand with us when we face prejudice and intolerance of our own?

Fighting against injustice should never be conditional, of course. Given both our history as a people and the moral foundations of our religious faith, Jews in this country and elsewhere always will be on the frontlines to battle against hatred and bigotry. But in the decades since Jewish activists played critical roles in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, the uncomfortable truth is that our relationship with the minority communities that have been the appropriate focus of the current protests has frayed considerably. There have been pockets of laudable cross-community dialogue and alliances, but on balance, the conversations are much less frequent, and the results are not nearly as impactful.

For years, the impact of this drift was most apparent in discussions about the safety and security of the State of Israel. Polling shows that Black and Latino voters are more likely to be supportive of the Palestinian cause than the overall electorate, and tensions between our communities on these issues have steadily grown on college campuses, within activist movements and in the halls of Congress. The clashes over the boycott and divestment movement and the possible conditionality of U.S. aid to Israel are getting fiercer, and the prominence of minority community leaders in these debates is growing as well.

But as examples of anti-Semitism in this country continue to increase at an alarming rate, our challenges are now closer to home. The California legislature has grappled for years over the question of mandated ethnic-studies classes for public school students. The original proposed curriculum was so saturated with anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic sentiment that it was hastily pulled back last summer for further review. But despite ongoing appeals from Jewish, Armenian, Hindu and other underrepresented groups, the core definition of “ethnic studies” still is limited to courses that focus on Native Americans, Blacks, Asian Americans, and Latina and Latino Americans, with no acknowledgement of the challenges, accomplishments or identity of any other marginalized community. Students fulfilling this requirement would finish their semester with no knowledge or understanding that the menace of discrimination and intolerance threatens a much broader audience than those four specific groups.

We will always fight for those who have been discriminated against — no matter what.

A central premise of ethnic-studies education is to confront latent hostilities toward those of other backgrounds by helping young people learn more about those cultures. Therefore, addressing hatred of Jews in that curriculum could have the same beneficial effect as discussions of other types of bigotry. But we may never know.

Majorities of Jewish Americans are deeply committed to the advancement of civil rights and to supporting communities of color as they strive for social justice. We will always fight for those who have been discriminated against — no matter what. But it does raise the question why prejudice against Jews so often is dismissed as a separate and lesser societal concern.

There’s no way to know whether continued Jewish participation in the racial justice discussion will create more support in communities of color when we advocate for our own goals. Either way, we will continue to stand against race-based hatred and discrimination. Hopefully, others will stand with us as well.

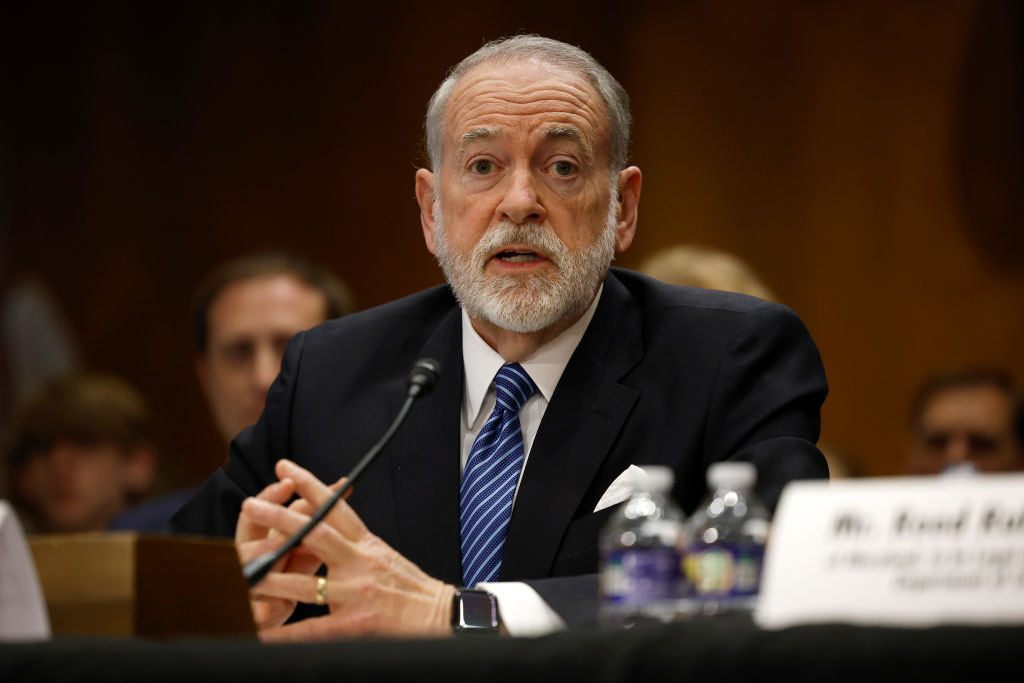

Dan Schnur teaches political communications at UC Berkeley.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.