The most essential question contained in Jewish liturgy is not, strictly speaking, in our liturgy. It’s the first two Aramaic words of several pages of block text small print with all the poetic ambition of a law-school textbook, crammed between prayer services, ostensibly as a stalling device. Everyone says these two words out loud — reflexively, like they’re reporting attendance — then races through the rest. In context, this question does not feel significant at all.

Yet I maintain that all of Judaism — religion, culture, life manual, reason to exist — boils down to the question we encounter shortly after the spiritual high point of Kabbalat Shabbat: Bameh madlikin? With what may we light?

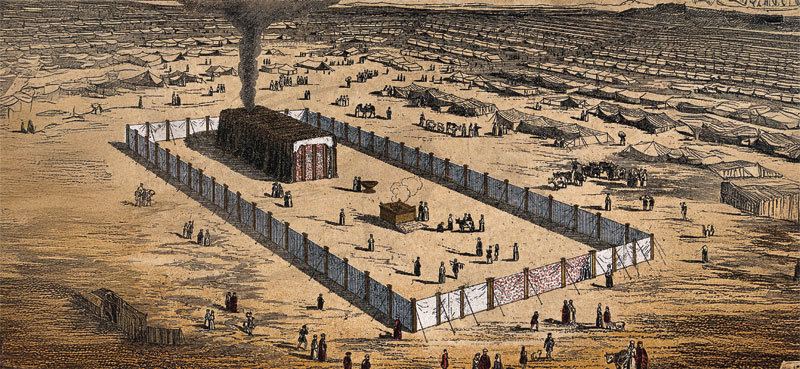

The ensuing Mishnayot discuss the permitted material composition of Shabbat candles. Admittedly, they are arcane and not a little whimsical. We can light using radish oil and fish oil but not uncombed flax. Seaweed’s a no-go, but boiled tallow? Go ahead — that is, if you hold by Nachum the Mede.

The dryness, so conspicuously placed in a moment of religious intimacy seems intentional. The passage presents as a technical counterpunch to the emotional intensity of the Psalms we just recited in Kabbalat Shabbat. There is no closeness to God without songs of praise, and there is no closeness to God without plumbing the depths of Torah observance for wonky hypotheticals. Bameh madlikin? Both.

In its rhetorical simplicity, the question also can go deeper. Bameh madlikin is a value check — a gut check. Yet, it contains multitudes. It floats usefully between “Will this do?” and “Is this sustainable?” and toggles between personal and communal outlooks. Yes, we can light with this, I say, finding myself out of step with some congregants at a new shul. Ein madlikin (We do not light); we have failed our obligation; this will not do, our leaders must say, when a man refuses to grant his wife a Jewish divorce. If we light with this, if our houses of worship are not accessible for the disabled or for the unhoused, or for the stranger who lives in our midst, we have not fulfilled the mitzvah.

In 2020, the questions Bameh madlikin stands for have changed. But it should be some consolation that the answers are no different. We know what our values are.

I have felt Bameh madlikin accelerate essential, long-term questions about my relationships and my politics, such as “Can I build a fulfilling life with this partner?” and “Can we build a society with these priorities?” But in recent weeks, it has assumed more urgent meaning as Judaism — Orthodoxy in particular — grapples with the ritual challenges of the coronavirus pandemic. Can we use a computer on Chag to host a virtual seder if that enables our less-observant family members to participate? Can we instruct people in quarantine to keep a three-day chag in full if that means cutting them off from society in a way that might be emotionally harmful to them?

Other versions of Bameh madlikin are being posed by the economic devastation wrought by non-essential business closures. Whether the full spectrum of Jewish life in a city can be nurtured and supported without a JCC is merely one of the many questions community leaders will face in the months ahead.

In 2020, the questions Bameh madlikin stands for have changed. But it should be some consolation that the answers are no different. We know what our values are. Let the story be that we remembered them and stuck to them when the chips were down.

And it wouldn’t be Bameh madlikin if it weren’t still a bit whimsical. As the quarantine continues, I have begun taking it as a survival challenge. Opening the cupboard to find canned vegetables, a bottle of hot sauce and a dusty tube of polenta — Bameh madlikin? Singing the songs of Kabbalat Shabbat as loudly as I can, to myself, in an empty, silent house — while facing east? Madlikin.

Back to the siddur. Toward the end of the passage, we read on Friday night is a word of caution. Playing loose with any of the following three mitzvot may cause a woman to die in childbirth, the Mishnah warns: the commandments of Niddah (the menstrual cycle), tithing the dough and lighting Shabbat candles. The stakes of Bameh madlikin are no less than life or death. Unheeded, it has the capacity to turn the miracle of humanity into utter loss — and by implication, the other way around.

That’s an uplifting message, not a dire one. It is permission to improvise with fish oil and radish oil and maybe even boiled tallow. It is an instruction to be resourceful and a guide for how to be resourceful as the losses in our community mount, as we feel farther and farther apart, and as the absence of communal Jewish practices begets new, individual routines. Finally, it is a promise that if we stay the course on the things that are truly non-negotiable, if we hold fast to what we really cannot light with or live without, we eventually will read (or race through) Bameh madlikin in shul together again. We will have a reason to.

Louis Keene is a writer living in Los Angeles. He’s on Twitter at @thislouis.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.