Ernie Fuld

Ernie Fuld PREVIOUSLY: Ernie finally gets his just desserts

Ernie was laid to rest on a warm Sunday morning in the spring of 2017.

There were six pallbearers to carry the simple pine box that was lowered into the ground at the Home of Peace Jewish cemetery in Oakland, Calif., as a handful of people gathered to commemorate the baker’s bittersweet life.

Marika was there, holding on to a close friend for emotional support. Morde and Marianne stood with their two daughters, along with Shoshana, Ernie’s card-playing pals and people who once worked in his bakery.

Sharon did not come.

The rabbi said a few words, but how do you sum up such an adventurous, combustible life? He then asked if anyone had anything to add, and the gathering, for a moment, went quiet. Marika was inconsolable, unable to speak.

Then Kelly Ehrenfeld, Morde’s daughter by a first marriage, stepped forward to haltingly read something she had written on her cell phone en route to the funeral.

Simply stated, it expressed a granddaughter’s love for a lost patriarch she never really understood, and her words might have even found their way to Ernie’s heart.

“My grandpa Ernie was definitely an interesting man,” she said. “He wasn’t loving in the traditional way. He wasn’t always easy to talk to and loved to give people a hard time.”

Because of the war, what he had endured.

“My grandpa spent so much of his life here focused on the terrible events he has suffered and survived,” Kelly said. “But he experienced much much more in this life than just the war. He married (several times), had children, and grandchildren, traveled all over the world, built a thriving business, and made a successful life for himself here.”

But there could be no eulogy about Ernie without Helen’s inclusion.

“Pretty much the only time I saw him get emotional was when we were in this exact same place for my grandmothers funeral 7 yrs ago,” Kelly said. “He spoke about how they had known each other for 60-plus years.

“Even though their marriage ended soon after it started, he said they remained good friends, something my grandma would say often also. He went on to talk about their life after the war, how they lived in refugee camps in Cyprus, then their escape to Israel.

“He started to tear up as he recalled their lives so long ago.”

She paused to collect herself. And then mentioned Ernie’s lost mother and brother.

“My hope is that he can rest In peace and love with his family that he lost so very long ago. Instead of spending eternity recounting stories of the war, my hope is that he can recount the adventures, the happiness, and the love he experienced in this life that his family missed out on.”

Of course, the funeral was fittingly bittersweet.

A former girlfriend who hadn’t talked to Ernie in years had read about his death in the newspaper, and felt compelled to come.

“Ernie was an asshole,” she told a listener.

Then she spoke about the help he had given her in life, words that seemed to be an absolution of his crimes.

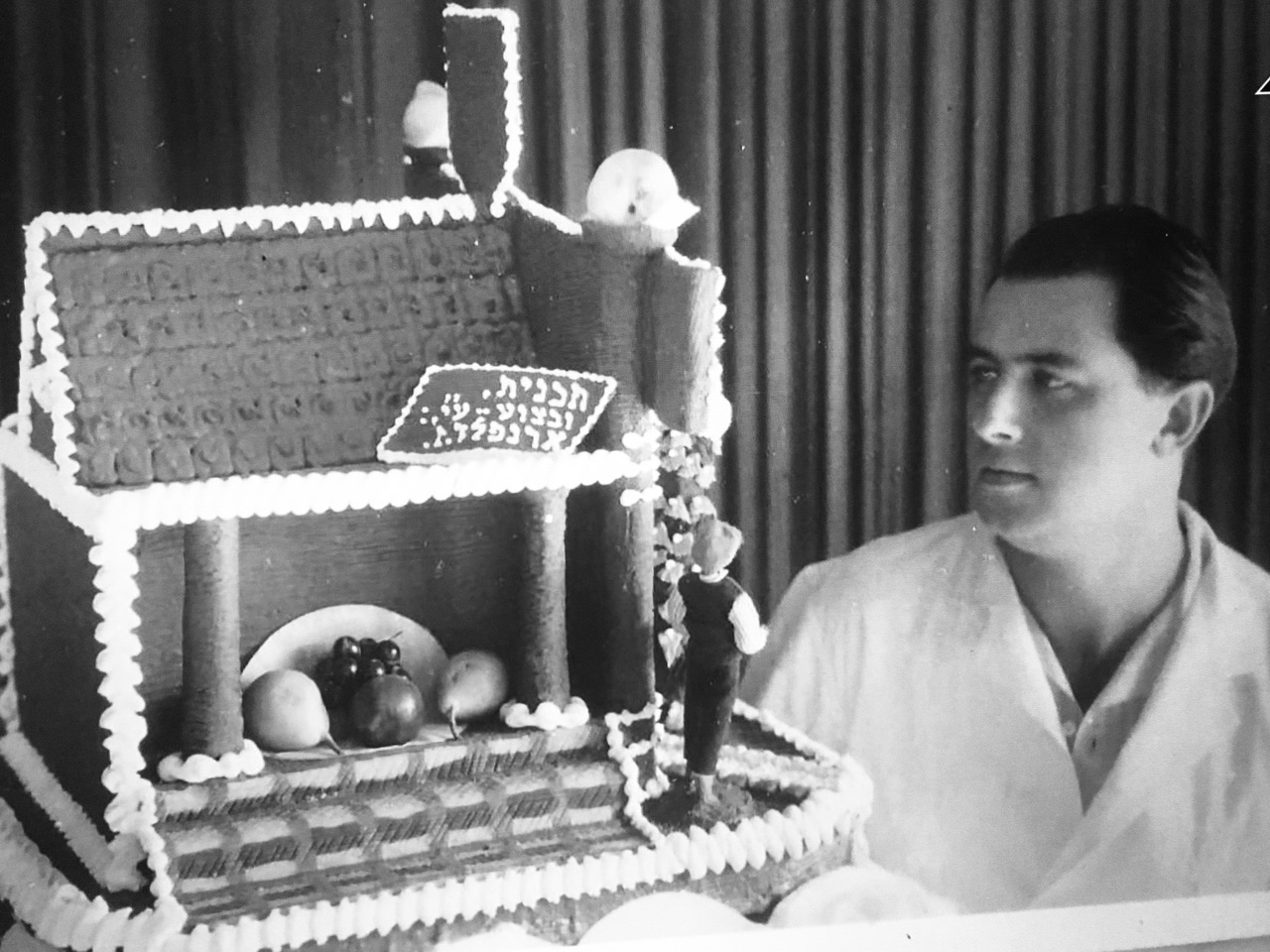

In life, Ernie’s talent was baking, but there was something more.

He was also a survivor. Scraping. Struggling. Sometimes hurtful. Taking no prisoners.

He outlasted the Nazis. The British camp. His own crazy emotional impulses.

With all that he endured, the beginning of the end came on his birthday, on February 21.

There was a bad snowstorm that day and Ernie and Marika drove down the mountain and east into Reno for Ernie’s regular medical checkup. They planned on stopping by a casino before having dinner and maybe spend the night before returning home.

Marianne warned him not to go, but it was like trying to change one of Ernie’s time-worn recipes at the last minute.

Impossible.

The snow was blowing sideways and Ernie’s car rammed into the back of a slow-moving snowplow, an almost immovable object. His crumpled car went underneath the big truck. Marika wasn’t injured, only Ernie

But Ernie did not die that day.

He survived again, at age 92, not yet ready to go.

He wanted more time to do a jig on the graves of his Nazi captors.

For weeks, he lay in the intensive care unit of a Reno hospital, confined to a neck brace, unable to speak.

Morde visited as often as he could, each time kissing his tempestuous father on the forehead.

Marianne came, too.

There were things she wanted to say.

“I told him ‘We love you. The grandkids love you. Your son, needless to say, jumps each time you call. he loves you, too.”

She encouraged Morde to tell his father that he loved him. “I think Ernie knew he was dying,” Marianne said. “It was time to say these things. He was a very, very very tough man. I understand.”

Morde admits that he’s too much like his father, that he often just says what needs to be said and nothing more.

“I wish I had more time with him,” he said. “But all he did was work.”

In the beginning, when he was a boy, Morde recalls, there were trips to Disneyland and the ski slopes. But then the bakery intervened.

Morde understands his father’s drive, why he demanded perfection in his kitchen.

“In baking, if you make one mistake, there’s a domino effect and everything could be ruined. For most of his life, my father believed that he had to do it all — the baking, the marketing, the buying and the selling,” he said.

“Nobody wanted to help him. I felt sorry for him. In the end, no one could stand him. But I don’t blame him. If he’s an asshole, then I’m an asshole, too.”

He paused.

“I miss him. We never did anything together, so how can I miss him? But I miss him.”

Kelly, who spoke at Ernie’s funeral, says her grandfather still comes up in conversations with her husband, even years after his death.

Once, at their wedding, they served ceviche and Ernie approached them and asked, “What was that shrimp salad you made? It was great!”

The next year, they drove up to Incline Village and made it for him specially.

She laughs about Ernie, still.

At her wedding, Kelly recalled, Ernie handed her husband a white plastic spoon. He thought it was some symbolic gesture, and later asked Ernie.

“What was that for?”

“To eat the cake!’ Ernie said.

Days before the 2017 funeral, Kelly found out she was pregnant. She has since delivered twins, a boy and a girl, now 2.

They never met their great-great grandfather.

But they will, through Kelly’s stories.

After Ernie finally passed away in early March, the family waited a few weeks for a spring burial. They could have went to another newer cemetery in San Francisco’s East Bay, but Morde wanted his father to rest in the same place as his beloved Helen.

On a hill overlooking the bay, Helen and her second husband, Maurice, are buried side by side. She’d always warned Ernie to buy himself a plot early, so he, too, could have a view and he wouldn’t burden his children with such matters after he was gone.

But he never did.

Before she died, she took Morde to the place and appealed to him.

“Look at the view!”

Being his father’s son, Morde’s response was deadpan.

“So, what, are all you guys gonna sit here and play cards together?”

So that’s where Ernie remains, down there in the shallows, without relatives nearby, beneath the high hill where the love of his life is buried next to another man, who gave her what he could not.

So close, and yet so very far.

Bittersweet, both in life and in death.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.