After the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, many Jews felt a profound sense of shock and sorrow. Michael Stanislawski, a professor of Jewish History at Columbia, put it this way: “A Jew had killed the prime minister of Israel! How could this have happened? How could the religious and political divides within Israel have descended to this low?” Stanislawski tried to get a better understanding of the Rabin assassination by studying previous instances of violence within the Jewish community; but there were very few cases to consider. For the first 1,750 years of exile, there were no instances of ideological violence. However, that changed in 1848 with the murder of Rabbi Abraham Kohn.

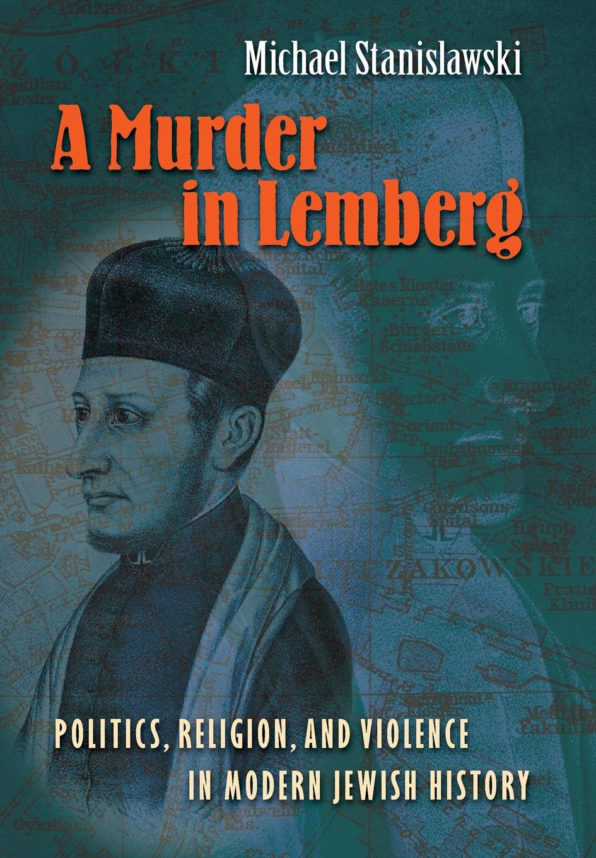

Stanislawski researched this now forgotten event, and published “A Murder in Lemberg: Politics, Religion, and Violence in Modern Jewish History.” It tells the story of Rabbi Abraham Kohn, who was appointed as a rabbi in Lemberg (now Lviv in Ukraine) in 1843. Although he had been ordained by the staunchly Orthodox Rabbi Samuel Landau of Prague, Kohn was a moderate reformer. He ultimately instituted reforms that would not raise any eyebrows today, such as a German language sermon and prayer for the government, abolishing the selling of aliyot, and having a professional cantor for the services. In 1846, a new progressive temple was dedicated, which would then serve as the seat of his rabbinate. Kohn’s sermon that day, which praised Emperor Ferdinand I of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, caught the attention of the authorities, and he was elevated to become the official Chief Rabbi of Lemberg.

Kohn’s new prominence stirred the anger of Orthodox extremists, who saw him as a religious threat. Pamphlets were circulated slandering Kohn as someone who eats non-kosher food and violates Shabbat. Aside from religious conflicts, several of Kohn’s opponents had ulterior motives for opposing him. Rabbi Kohn was lobbying for an end to taxes on kosher meat and candles that the government had levied on the Jewish community. Although these taxes were discriminatory, many powerful Jewish leaders profited from these taxes; they were tax farmers who paid the government a flat fee for the right to levy these taxes on others. Kohn was a financial threat to them as well.

During Pesach in 1848, a mob descended upon the Jewish communal offices demanding that Rabbi Kohn be relieved of his post; there was so much mayhem that the leader of the mob was arrested. At that point, Rabbi Kohn’s wife Magdalena begged him to consider moving away from Lemberg. Kohn’s response was: “I am after all among Jews; what will they do to me in the end?” His naivete is understandable; at that time, Jewish ideological violence was unthinkable.

But the threats to Kohn continued to escalate. At the beginning of September, placards were placed in synagogues declaring Kohn to be a poshea Yisrael, a willful sinner, who needed to be removed from his position. Kohn responded to this intensifying campaign with a call to end violence. His final sermon was preached on the topic of “thou shalt not kill.”

On September 6 1848 Kohn was murdered. A thirty-year-old goldsmith by the name of Abraham Ber Pilpel visited the Kohns’ apartment, sneaked into the kitchen under the guise of lighting his cigar, and poured arsenic into the soup. When the soup was served to the family, Magdalena noticed something was wrong, but the rabbi dismissed the strange taste as too much pepper in the soup, and proceeded to finish his bowl. The entire family became ill right away. Magdalena, suspecting that they might have been poisoned, immediately called for a doctor. However, it was too late, and Kohn and his baby daughter Teresa died.

A subsequent investigation fingered Pilpel as the murderer, but indicated he had colluded with two prominent Orthodox leaders, Jakob Herz Bernstein and Hirsch Orenstein, who were arrested as well. Bernstein and Orenstein had been leaders in the campaign against Kohn, and were also wealthy tax farmers. Sadly the investigation went nowhere, and no one was convicted of the crime. (Even more heartbreaking is that Hirsch Orenstein would become the Chief Rabbi of Lemberg in 1878).

Stanislawski’s review of the files and newly found evidence leads him to the conclusion that Pilpel almost certainly committed the murder, and probably at the instigation of the others. For the first time in 1,800 years, a Jew had murdered another Jew for ideological reasons.

For the first time in 1,800 years, a Jew had murdered another Jew for ideological reasons.

The rebellion of Korach in our Torah reading is a political battle, with Korach attempting to replace Moshe and Aharon as the leaders of the Jewish people. But the Talmud sees this story as relevant to everyday events, and the rebellion of Korach as simply an unhealthy dispute. The Talmud says that “anyone who perpetuates a dispute violates a prohibition, as it is stated: ‘And you should not be like Korah and his assembly.’” This, according to the 14th-century Italian Rabbi Isaiah ben Elijah di Trani, requires us to be forbearing and understanding in personal disputes. Without a bit of forgiveness, every dispute will end up being as toxic as Korach’s.

Even more fascinating is a passage in the Mishnah which says:

“Every dispute that is for the sake of Heaven, will in the end endure; but one that is not for the sake of Heaven, will not endure. Which is the controversy that is for the sake of Heaven? Such was the controversy of Hillel and Shammai. And which is the controversy that is not for the sake of Heaven? Such was the controversy of Korah and all his congregation.”

This Mishnah is puzzling: what does it mean when it says that the dispute will endure or not endure? Rabbi Yehuda Herzl Henkin notes that we certainly remember Korach’s dispute every year when we read this Parsha; it has endured in the memory of the Jewish people. And as far as Shammai and Hillel, no one continues to argue for Shammai’s views! So what is the Mishnah saying?

Rabbi Henkin explains that the word “endures” refers to whether the two sides will continue to talk to each other and debate the issues. When Moshe reaches out to Korach’s associates Datan and Aviram to come and speak with him, they emphatically respond, “We will not come!” When Shammai and Hillel debated, they continued to talk, and debate, and then debate again with each other; some of the debates took two and half years. All the while, Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai married and socialized with each other. If you are debating for the sake of heaven, you can still love the person you disagree with. This is what the Mishnah means by saying “the dispute will endure”: both parties will still talk, instead of unfriending each other because of the disagreement.

If you are debating for the sake of heaven, you can still love the person you disagree with.

This is a profound insight, and in the growing academic discipline of Conflict Resolution, empathy for the other side is critical to creating a lasting end to conflict. And in marriage therapy, empathy is the anchor that can carry a couple through the most difficult marital conflicts. What gets lost in heated debates is our God-given ability to have compassion for each other.

The relative lack of political violence in the Jewish community during the years of exile is an anomaly. There had been many violent power struggles during the First and Second Temple periods. But it was in exile that violence became taboo because every Jew felt the sting and hurt of discrimination; that made it easy to empathize with other Jews, no matter how different they were, and ideological violence seemed impossible. But in 1848, this taboo was breached; and with the Rabin assassination, it was breached again.

But it was in exile that violence became taboo because every Jew felt the sting and hurt of discrimination; that made it easy to empathize with other Jews, no matter how different they were, and ideological violence seemed impossible.

It is painful to read the Parsha of Korach on a week when the dark clouds of violence are on the horizon once again, and several politicians in Israel now need ‘round-the-clock security due to death threats. Exile has taught us that unity is the only choice for the community; and the Talmud has taught that empathy is the only choice for the future. We must remember these lessons before it’s too late.

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz is the Senior Rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in New York.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

Korach: Hatred or Unity

Chaim Steinmetz

After the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, many Jews felt a profound sense of shock and sorrow. Michael Stanislawski, a professor of Jewish History at Columbia, put it this way: “A Jew had killed the prime minister of Israel! How could this have happened? How could the religious and political divides within Israel have descended to this low?” Stanislawski tried to get a better understanding of the Rabin assassination by studying previous instances of violence within the Jewish community; but there were very few cases to consider. For the first 1,750 years of exile, there were no instances of ideological violence. However, that changed in 1848 with the murder of Rabbi Abraham Kohn.

Stanislawski researched this now forgotten event, and published “A Murder in Lemberg: Politics, Religion, and Violence in Modern Jewish History.” It tells the story of Rabbi Abraham Kohn, who was appointed as a rabbi in Lemberg (now Lviv in Ukraine) in 1843. Although he had been ordained by the staunchly Orthodox Rabbi Samuel Landau of Prague, Kohn was a moderate reformer. He ultimately instituted reforms that would not raise any eyebrows today, such as a German language sermon and prayer for the government, abolishing the selling of aliyot, and having a professional cantor for the services. In 1846, a new progressive temple was dedicated, which would then serve as the seat of his rabbinate. Kohn’s sermon that day, which praised Emperor Ferdinand I of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, caught the attention of the authorities, and he was elevated to become the official Chief Rabbi of Lemberg.

Kohn’s new prominence stirred the anger of Orthodox extremists, who saw him as a religious threat. Pamphlets were circulated slandering Kohn as someone who eats non-kosher food and violates Shabbat. Aside from religious conflicts, several of Kohn’s opponents had ulterior motives for opposing him. Rabbi Kohn was lobbying for an end to taxes on kosher meat and candles that the government had levied on the Jewish community. Although these taxes were discriminatory, many powerful Jewish leaders profited from these taxes; they were tax farmers who paid the government a flat fee for the right to levy these taxes on others. Kohn was a financial threat to them as well.

During Pesach in 1848, a mob descended upon the Jewish communal offices demanding that Rabbi Kohn be relieved of his post; there was so much mayhem that the leader of the mob was arrested. At that point, Rabbi Kohn’s wife Magdalena begged him to consider moving away from Lemberg. Kohn’s response was: “I am after all among Jews; what will they do to me in the end?” His naivete is understandable; at that time, Jewish ideological violence was unthinkable.

But the threats to Kohn continued to escalate. At the beginning of September, placards were placed in synagogues declaring Kohn to be a poshea Yisrael, a willful sinner, who needed to be removed from his position. Kohn responded to this intensifying campaign with a call to end violence. His final sermon was preached on the topic of “thou shalt not kill.”

On September 6 1848 Kohn was murdered. A thirty-year-old goldsmith by the name of Abraham Ber Pilpel visited the Kohns’ apartment, sneaked into the kitchen under the guise of lighting his cigar, and poured arsenic into the soup. When the soup was served to the family, Magdalena noticed something was wrong, but the rabbi dismissed the strange taste as too much pepper in the soup, and proceeded to finish his bowl. The entire family became ill right away. Magdalena, suspecting that they might have been poisoned, immediately called for a doctor. However, it was too late, and Kohn and his baby daughter Teresa died.

A subsequent investigation fingered Pilpel as the murderer, but indicated he had colluded with two prominent Orthodox leaders, Jakob Herz Bernstein and Hirsch Orenstein, who were arrested as well. Bernstein and Orenstein had been leaders in the campaign against Kohn, and were also wealthy tax farmers. Sadly the investigation went nowhere, and no one was convicted of the crime. (Even more heartbreaking is that Hirsch Orenstein would become the Chief Rabbi of Lemberg in 1878).

Stanislawski’s review of the files and newly found evidence leads him to the conclusion that Pilpel almost certainly committed the murder, and probably at the instigation of the others. For the first time in 1,800 years, a Jew had murdered another Jew for ideological reasons.

The rebellion of Korach in our Torah reading is a political battle, with Korach attempting to replace Moshe and Aharon as the leaders of the Jewish people. But the Talmud sees this story as relevant to everyday events, and the rebellion of Korach as simply an unhealthy dispute. The Talmud says that “anyone who perpetuates a dispute violates a prohibition, as it is stated: ‘And you should not be like Korah and his assembly.’” This, according to the 14th-century Italian Rabbi Isaiah ben Elijah di Trani, requires us to be forbearing and understanding in personal disputes. Without a bit of forgiveness, every dispute will end up being as toxic as Korach’s.

Even more fascinating is a passage in the Mishnah which says:

“Every dispute that is for the sake of Heaven, will in the end endure; but one that is not for the sake of Heaven, will not endure. Which is the controversy that is for the sake of Heaven? Such was the controversy of Hillel and Shammai. And which is the controversy that is not for the sake of Heaven? Such was the controversy of Korah and all his congregation.”

This Mishnah is puzzling: what does it mean when it says that the dispute will endure or not endure? Rabbi Yehuda Herzl Henkin notes that we certainly remember Korach’s dispute every year when we read this Parsha; it has endured in the memory of the Jewish people. And as far as Shammai and Hillel, no one continues to argue for Shammai’s views! So what is the Mishnah saying?

Rabbi Henkin explains that the word “endures” refers to whether the two sides will continue to talk to each other and debate the issues. When Moshe reaches out to Korach’s associates Datan and Aviram to come and speak with him, they emphatically respond, “We will not come!” When Shammai and Hillel debated, they continued to talk, and debate, and then debate again with each other; some of the debates took two and half years. All the while, Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai married and socialized with each other. If you are debating for the sake of heaven, you can still love the person you disagree with. This is what the Mishnah means by saying “the dispute will endure”: both parties will still talk, instead of unfriending each other because of the disagreement.

This is a profound insight, and in the growing academic discipline of Conflict Resolution, empathy for the other side is critical to creating a lasting end to conflict. And in marriage therapy, empathy is the anchor that can carry a couple through the most difficult marital conflicts. What gets lost in heated debates is our God-given ability to have compassion for each other.

The relative lack of political violence in the Jewish community during the years of exile is an anomaly. There had been many violent power struggles during the First and Second Temple periods. But it was in exile that violence became taboo because every Jew felt the sting and hurt of discrimination; that made it easy to empathize with other Jews, no matter how different they were, and ideological violence seemed impossible. But in 1848, this taboo was breached; and with the Rabin assassination, it was breached again.

It is painful to read the Parsha of Korach on a week when the dark clouds of violence are on the horizon once again, and several politicians in Israel now need ‘round-the-clock security due to death threats. Exile has taught us that unity is the only choice for the community; and the Talmud has taught that empathy is the only choice for the future. We must remember these lessons before it’s too late.

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz is the Senior Rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in New York.

Did you enjoy this article?

You'll love our roundtable.

Editor's Picks

Israel and the Internet Wars – A Professional Social Media Review

The Invisible Student: A Tale of Homelessness at UCLA and USC

What Ever Happened to the LA Times?

Who Are the Jews On Joe Biden’s Cabinet?

You’re Not a Bad Jewish Mom If Your Kid Wants Santa Claus to Come to Your House

No Labels: The Group Fighting for the Political Center

Latest Articles

Israel Strikes Deep Inside Iran

NSFW – A Poem for Parsha Metzora

Israel War Room Launches in Spanish

Modern Book Bans Echo Past Atrocities and Further Silence Marginalized Voices

The Power of the Passover Seder to Unite Jews

Dr. Nicole Saphier Reflects on Motherhood and Jewish Advocacy

Culture

Make Felt Seder Plate Elements

Oct. 7 Events to Be Depicted in New Stage Show

Shani Seidman: Manischewitz, Passover Memories and Matzo Brei

Was Spinoza a Victim of Cancel Culture?

Israel’s David Moment

How Iran’s attack on the Jewish state could help unify a fractured Middle East

Beit Issie Shapiro Gala, David Labkovski Exhibit, de Toledo College Signing Day, JFSLA Shabbat

Notable people and events in the Jewish LA community.

Is Aaron’s Haroses the New Hummus?

Aaron Weiner, Founder of Aaron’s Haroses, wants to make haroses – aka charoset – a year-round treat.

A Bisl Torah – Ask These Questions

The shackles of ancient Egypt feel ever present. The nightmare isn’t over.

Four Sons Saved by Elijah

Hollywood

Spielberg Says Antisemitism Is “No Longer Lurking, But Standing Proud” Like 1930s Germany

Young Actress Juju Brener on Her “Hocus Pocus 2” Role

Behind the Scenes of “Jeopardy!” with Mayim Bialik

Podcasts

Shani Seidman: Manischewitz, Passover Memories and Matzo Brei

Joan Nathan: “My Life in Recipes” and Pecan Lemon Torte

More news and opinions than at a

Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.