While shopping at Target one day, a man pushing a cart filled with household items sidled over to me and asked, “Do you know where I can find the closest keilim mikveh?”

There were probably 100 other shoppers at the time, but my “uniform” of below-the-knee skirt, below-the-elbow shirt, and colorful beret alerted the man that I, and perhaps I alone in this megastore, could direct him to a mikveh used for ritual immersion of new dishes and cookware, which I did happily.

My outfits mark me as identifiably Jewish, and Jews across the observance spectrum react in different ways. From urban malls to the great outdoors of Yosemite, frum Jews who see one another offer a subtle but definitive nod of recognition, a silent greeting that says, “Shalom Aleichem.” Or simply, “Yo, Hebrew sister.”

Non-Orthodox Jews also are eager to signal their status as Members of the Tribe (MOTs). They start “bageling,” striking up a little conversation and tossing in a Yiddish or Hebrew word like a conversational wink: “I bet you’re getting ready for Shabbos!” one said to me on a Friday afternoon as we shared an elevator ride, emphasizing the Yiddish pronunciation. I am touched by these encounters, by the effort to show kinship, the statement of pride that they, too, are Jews.

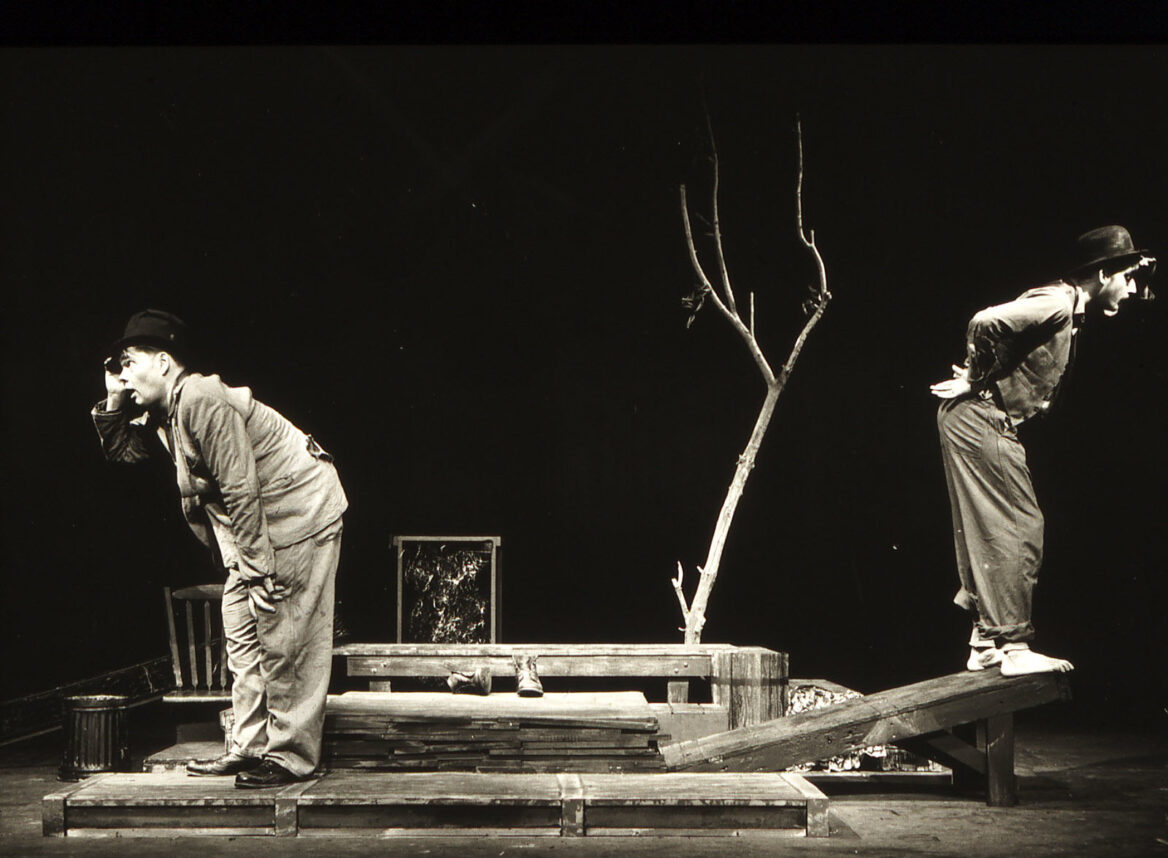

Sometimes, though, what begins on a light note can become unexpectedly intense. For example, once I gambled on a laughter yoga class, looking for laughs more than for a new way to hold my Uttanasana pose. I hung back during a few of the “exercises,” because it would have been too awkward for me to do them in such close range with men. After the class, two MOT sisters took me aside and peppered me with questions. How was I “allowed” to go to a mixed event like this, with men and women together? Did I go to a regular gym? Did I grow up this way? They were genuinely curious but I had to suppress a laugh at their phraseology, as if growing up “this way” was like growing up with some deformity, such as a club foot.

All Jews are meant to be figurative candles in the “light unto the nations” that God has given us as our mission.

I welcomed their questions, so they dug deeper, finally getting to the nub of the kosher biscuit. One of them challenged, “Isn’t it true that Jews like you look down on Jews like us because we don’t keep the laws like you do? We’re just as Jewish as you are.”

Oy, who knew that laughter yoga was such a fertile ground for intra-Jewish relations?

“Yes, of course you are.” I said. “We are meant to love our fellow Jews, not reject them, though we may reject and judge actions that go against the Torah.” I told them that I only began keeping Shabbos in my 20s, and advanced in observance very slowly. We are all growing Jews, I said, or at least, we should think of ourselves that way. They seemed to listen carefully and appreciatively.

All Jews are meant to be figurative candles in the “light unto the nations” that God has given us as our mission. While we are equally responsible, when we openly present ourselves as Jewish through our clothing, the responsibility is even greater. People know we’re Jewish. They are quick to notice if we are rude or otherwise behave in ways less kosher than our clothing. More than once, I’ve held my tongue when I wanted to make a critical remark to someone, held back from honking at an annoying driver. My actions are my own, but they reflect on the whole mishpachah.

It’s a mitzvah to show the world a pleasant expression (seyver panim yafot). Our open and friendly expressions invite the possibilities for these fleeting, yet somehow notable, connections with Jews who would otherwise be out of our orbit. It can be a simple nod of kinship, an opportunity to dispel myths and offer reassurance that what we have in common is greater than what divides us. And sometimes, it may simply be the opportunity to offer directions to the nearest dish mikveh.

Judy Gruen is the author of “The Skeptic and the Rabbi: Falling in Love With Faith.”v

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.