For all the anti-Semitism-based controversy roiling the Women’s March, we in Los Angeles who took part last year should have no crisis of conscience about doing so again on Jan. 19. Women’s March Los Angeles is separate from the national group. Many participating Jews incorporate observing Shabbat around the march (booking rooms downtown, davening early).

But what is happening with the national march committee? Ominous conversations about anti-Semitism have gone public. Jewish women, including members of Bend the Arc and the National Council of Jewish Women continue to have urgent meetings with the national leadership team to address issues of anti-Semitism and racism, trying to call one another in (not call one another out). Linda Sarsour, a Women’s March board member, found it necessary to issue an apology, stating, “We should have been faster and clearer in helping people understand our values and our commitment to fighting anti-Semitism. We regret that. Every member of our movement matters to us — including our incredible Jewish and LGBTQ members. We are deeply sorry for the harm we have caused, but we see you, we love you, and we are fighting with you.”

The Unity Statement for the national march includes, “We must create a society in which all women — including Black women, Indigenous women, poor women, immigrant women, disabled women, Jewish women, Muslim women, Latinx women, Asian and Pacific Islander women, lesbian, bi, queer and trans women — are free …” Yet some are saying that this is not enough. What happened and how should we respond? No one ought to expect that members of a broad coalition agree about every issue. What lines should not be crossed?

One key point: My governing assumption here is that Jews necessarily have an interest in intersectional politics, because we live at intersections: We are Jews and women, Jews and queer, Jews and people of color and, yes, Jews and working class. Just as each woman is a woman. Intersectionality represents the principle that none of us is free unless each of us is free. We who annually celebrate our delivery from slavery and the command to love the stranger are bound by that.

We must never forget that those movements intersect in the bodies of Jews of color for whom we are obliged to stand.

Two key issues around the march have been crystalized in conflicts with personalities, that of Sarsour and National Co-Chair Tamika Mallory. Sarsour is adamantly opposed to Israeli government policies and supports the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel. She also has raised thousands of dollars to aid American-Jewish communities whose cemeteries have been desecrated, and built strong personal friendships with Jewish women.

Regarding Sarsour, either one agrees with her that it is possible to support the BDS movement while not being anti-Semitic, or one does not. (I believe that it is possible.) If one believes that anti-Zionism necessarily equals anti-Semitism, then either it is acceptable to participate in a march with a leading organizer who holds an unconscious bias against oneself, as long as that the organizer commits to dialogue with Jewish people — or it is not. (I believe that it is.)

The conversations with Mallory that have emerged raise crucial issues about racism and anti-Semitism; about where movements on behalf of people of color, black people specifically, and Jews ought to intersect. Above all, we must never forget that those movements intersect in the bodies of Jews of color for whom we are obliged to stand.

The problem is that Mallory, a Christian, has a longstanding relationship with the Nation of Islam (NOI), whose leader Louis Farrakhan stands firm in his ideologically driven hatred of Jews, lesbians, gays and gender non-conforming people. This puts Farrakhan at odds with most of the march’s Principles of Unity. Yet Mallory won’t disavow her working relationship with Farrakhan or the NOI, which practices an adulterated Islam, unacceptable to mainstream Muslim thinkers.

Adam Serwer, a biracial, black Jewish man has written an indispensable article for The Atlantic on this question. As “unworthy” of Mallory’s loyalty as he finds Farrakhan to be, Serwer points out that, for serious organizers within black communities, the NOI is impossible to dismiss. “But many black people come into contact with the Nation of Islam as a force in impoverished black communities — not simply as a champion of the black poor or working class, but of the black underclass: black people, especially men, who have been written off or abandoned by white society. They’ve seen the Fruit of Islam patrol rough neighborhoods and run off drug dealers, or they have a family member who went to prison and came out reformed, preaching a kind of pride, self-sufficiency, and entrepreneurship that, with a few adjustments, wouldn’t sound out of place coming from a conservative Republican. The self-respect, inner strength, and self-reliance reflected in the polished image of the men in suits and bow ties can be a powerful sight.”

Farrakhan also has indicated that he regards Jews to be a demonic force, the masterminds behind the social transformation of sexuality and gender in our world. This means that we should not mistake Farrakhan’s ravings for “anti-Semitism of the left.” Farrakhan is a deeply conservative demagogue who advocates male supremacy and retains a touching faith in unregulated capitalism despite what it never did for his people. (Think of him as a black Jordan Peterson, and it all snaps into place.)

The generation that created Black Lives Matter, a movement led by queer, black women articulating an intersectional politics that speaks to race, class, sexuality and gender, will render Farrakhan irrelevant soon enough — if that generation takes up the work of connecting with prisoners, addicts and other marginalized people. This applies to religious progressives of all traditions — including Jews.

Interestingly, Farrakhan’s fantasy of powerful Jews pulling invisible strings echoes a trope that drives today’s white nationalist movement. As Erik K. Ward writes in his insightful article “Skin in the Game,” “Antisemitism forms the theoretical core of White nationalism.” When white nationalists chant “Jews will not replace us,” they mean that, just as Farrakhan believes that LGBTQ people are being secretly manipulated by a Jewish cabal, so, too, are people of color and immigrants who, the racists believe, could never organize to defend their interests on their own and are being driven by Jews into “replacing” white people within job markets and neighborhoods from which they’ve been previously excluded.

So Jews have a stake in intersectional politics. Who benefits if the Women’s March, a key site of the anti-Trumpism, pro-democracy resistance, is fractured? What would be the point of turning away from urgent conversations among people who wish to build a world in which we are all free to practice our traditions, earn a living and breath clean air?

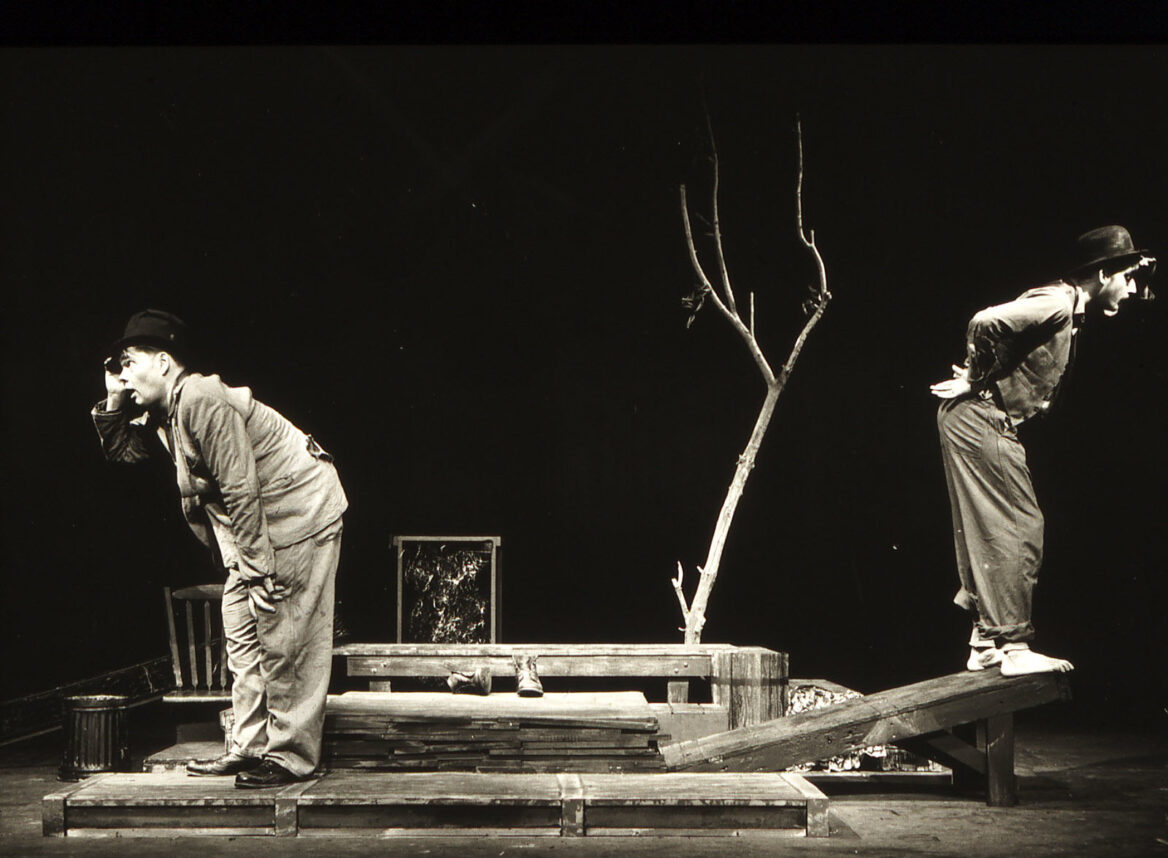

As my friend and teacher, Rabbi Rachel Adler says, “I’ve had lectures from many Jewish men about boycotting the Women’s March. They seem oblivious that Jewish women share the gender oppressions the Women’s March protests, even the privileged segment of Jewish women who are heterosexual and white. None of the men who demand that we boycott the march have pledged to help us eradicate sexual harassment and assault, pay inequities or glass ceilings in Jewish camps, schools, synagogues and communal institutions — or volunteered to examine their own disrespectful gender practices: interrupting women while they speak, appropriating women’s words and ideas, [making] intrusive comments on appearance and clothing or unwanted touching. I will go to the Women’s March as the Jewish woman I am with my kippah on my head. Possibly I’ll get ignored or disrespected or tossed out. But I’ve a lifetime of practice dealing with all that with Jewish men.”

Rabbi Robin Podolsky teaches at Cal State Long Beach, writes for Shondaland, and blogs at jewishjournal.com/erevrav.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.