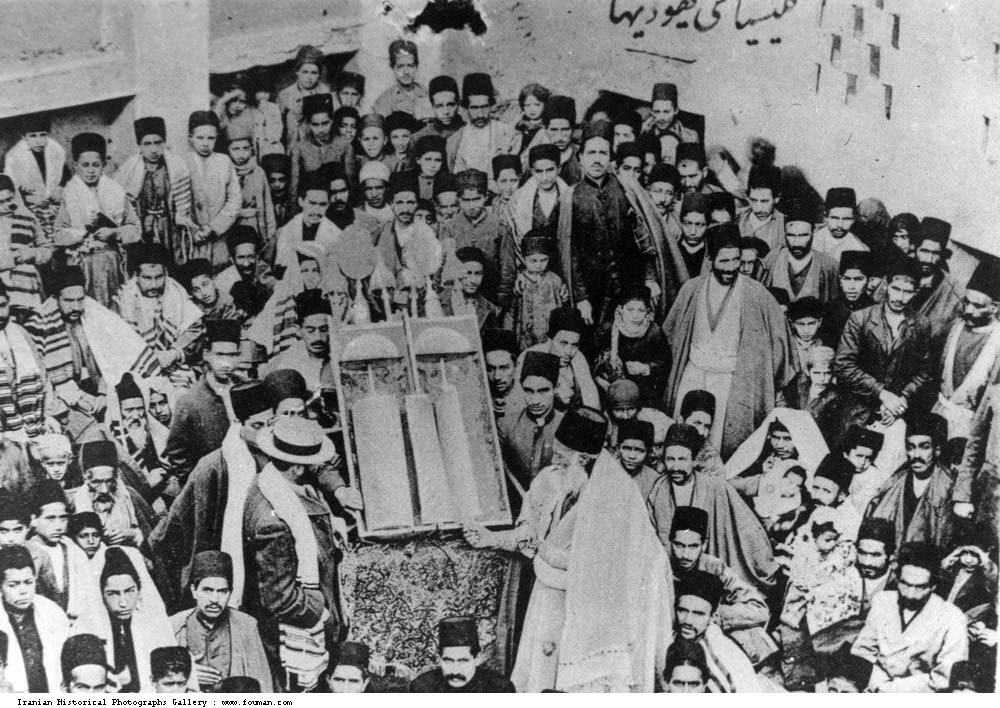

I’ve had the rare honor of reporting on my community of Iranian Jews living in America, Israel, Europe and even in Iran for nearly 20 years. I have interviewed thousands of them, covering their stories of survival, overcoming anti-Semitism in Iran, escape from Iran after the revolution and new found successes in America. Some of their stories I have had published within articles but many I have not due to limited space or requests for the stories not to be shared with the world. From time to time I am either approached by or receive e-mails from American Ashkenazi Jews living in Los Angeles or New York who have read these stories and wonder what their relevance is today. Many times they ask “why are you still writing about what happened to Jews in Iran during the revolution of 1979? After all many of you Iranian Jews living in America are quite successful and wealthy”. Or some make comments like; “you write about events from decades ago in Iran, why can’t you let go of the past of what happened to you as Jews living in Iran and move on?” My response to all of these comments and questions are simple… one can never forget an injustice done to them– especially the Jews of Iran who had been living in that country for nearly 2,700 years before being forced out. I typically share one heart-wrenching story from a 93-year-old Iranian Jewish retired businessman who I interviewed 15 years ago prior to his death to explain the heartache we as Iran’s Jews faced. His story is perhaps one of the best examples of why many in Iranian Jews living in America or elsewhere in the world still feel deep pain and sense of injustice brought upon them by Iran’s current radical Islamic regime.

The story is about a 93-year-old Iranian Jewish retired businessman, who I will name Samuel P., to protect his identity even though he has long passed away. His story starts back when he was born to Jewish parents at the turn of the 20th century in the Iranian northern coastal city of Rasht. Located on the shores of the Caspian Sea, the city was a hub of commerce due to its close proximity to Russia and to what is now Azerbaijan. His father was a blonde-hair blue eyes Jewish carpenter who had fled the Russian pogroms and resettled in Rasht. His mother was a daughter of a Jewish fishmonger in the city’s Jewish ghetto. Their family barely survived and was forced to live in the city’s poverty-stricken Jewish ghetto. At that time, Jews because of their inferior status in Iran, were forced to live in horrid dirty run-down ghettos. As a child he was beaten and or spit on regularly by Muslim children and even kicked by Muslim adults because of his Jewish faith. They called him “najes” which is a Farsi word for ritually impure and he experienced horrific anti-Semitism from the city’s Muslims on a daily basis which made him fear for his life.

As if Samuel’s life could not get harder, by age 13 his father died and he was forced to leave school in order to find work in order to feed himself, his mother and his two siblings. His mother found work cooking meals for Jewish families who were having weddings or larger festivities and this permitted her to often bring home extra food left over. At first he could find no work among the city’s limited Jewish businesses because they barely made enough to feed them own families, let alone pay a young boy to work for them. Yet he did manage to eventually work as a courier of sorts for a local affluent Muslim trader who imported Russian goods and sold them across Iran. He said the trader felt sorry for him because he wore torn clothing and old leather shoes with holes in their soles. Yet the businessman gave him equivalent to one dollar a week pay for doing odd jobs such as dropping off messages or boxes of goods around town for him. Samuel said he worked hard for the Muslim businessman from sunrise to sundown every day of the week, except Friday which is the Muslim Sabbath day. Many nights he was too tired to even eat and went straight to sleep, giving his mother whatever earnings he had received.

The exhaustive daily struggle for survival continued for Samuel and his family until he was nearly 20 years old. One day his luck changed when he was cleaning windows inside his boss’s office and a letter arrived in French language for his boss. Not knowing any French, his boss grumbled about finding anyone in the city who had any fluency in French and could help him correspond with the French company who had sent the letter. Without hesitation or any difficulty, Samuel asked for the letter and quickly translated it for his boss. A look for utter shock came over the trader’s face that his young man who had been working as his day laborer, doing odd jobs had fluency in French. “He asked me how I spoke and read French so well and I replied that I had gone to a French Jewish school at one time prior to my father dying that was set-up to educate Iranian Jewish children in the city”, Samuel said during his interview with me. The letter was from a French chemical company who had set up offices in Baku and wanted to sell their chemicals to the Muslim businessman who was based in Iran. Instantly, his boss began doing business with the French company with the help of Samuel’s language skills and his Muslim boss surprisingly rewarded him with higher pay. The additional money was of great help to Samuel and his family who would be able to avoid hunger and many of the hardships of poverty the Jews of Rasht experienced during that time period.

After several years of savings his own money, learning the chemicals business and forging connections with chemical manufacturers outside of Iran, Samuel ventured out on his own and started a business importing industrial chemicals into Iran. The struggle to make this business a success was difficult as Jews were not typically involved in this industrial level of commerce in the country, however Samuel’s hard work eventually paid off. With U.S. and foreign forces occupying Iran by the start of World War II, those companies based in Iran who had or manufactured industrial goods in the country made money selling their goods to the allied armies in the country. Samuel’s industrial chemicals were a hot commodity and eventually his entire inventory was purchased by the American and Russian armies with a year. He used the profits for the sale of the goods to begin manufacturing some of the chemicals he had once imported from Europe. By the end of the war, he was fairly well off and moved to Tehran to expand his chemicals business.

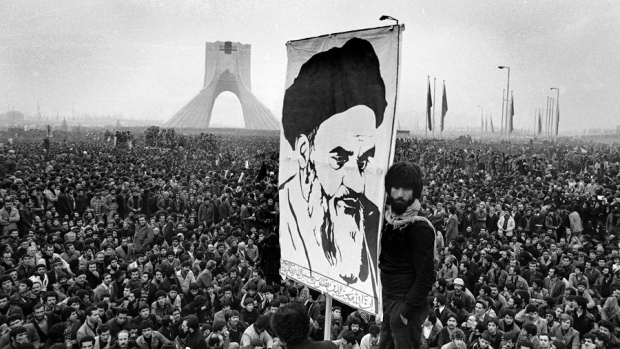

By the late 1970s, Samuel had amassed a huge fortune and become of the leading industrialists in Iran dealing with the chemicals business. His company had several hundred employees and sold chemicals not only throughout Iran but in much of the Middle East and even parts of the former Soviet Union. He had married, had children and even grandchildren. The years of hard work, suffering anti-Semitism and struggles of making a business a success after building it from scratch had paid off for him. Just as he was thinking of enjoying an easier life in his retirement years, the rug was literally yanked from underneath him when the regime of the Shah collapsed and the ayatollahs took power in Iran. Overnight, the status of Jews and other religious minorities was changed throughout Iran to third class citizens and they were subject to threats, arrests, tortures, executions and other dangers. Being an affluent Jew made Samuel a prime target for the new radical Islamic regime of the ayatollahs that immediately confiscated his successful business, his personal as well as business bank accounts and his business properties. He was imprisoned and beaten daily in the notorious Evin prison in Tehran on false charges of spying for Israel. His captors who were the new radical Islamic thugs wanted him to sign over the deed to his home and give them access to his supposed financial accounts overseas in exchange for his freedom. He refused to give into his captors and the beatings continued for nearly three months with his teeth smashed and his legs broken.

Samuel would have probably died in that jail cell or even been executed had his wife and a former employee not intervened on his behalf. As luck would have it, Samuel’s former employee, Ali-Reza, who was a driver and personal assistant, was informed of Samuel’s fate by a relative who was also a guard at Evin prison. Samuel’s wife Sarah gave some of her jewelry to Ali-Reza who handed it to his relative and asked the relative to free Samuel in the middle of the night. The bribe worked and Samuel was miraculously smuggled out of the prison in the back of a van after pretending to be dead in his jail cell. That very night, Samuel, his wife and his children fled Tehran and made their way to the Pakistani border. They eventually paid opium smugglers to smuggle them out of Iran in a journey that was life-threatening and something of a feature film in itself! After months in Pakistan, Samuel was able to make it to Austria and eventually to Los Angeles by 1984.

This self-made Iranian Jewish man, had escaped Iran with his family but was forced to leave behind his entire fortune that he had worked so hard to earn with blood, sweat and tears. Now in his early 60s with very little money, no friends, no resources and living in a foreign land, Samuel had to restart his life again from scratch and also feed his family. While he spoke a limited amount of English, his French was perfect and he surprisingly found work as a court appointed translator of French language in the L.A. court system. Later one he also worked as a travel agent for a French travel agency based in L.A. His wife worked as a cook for a local catering company and his college-aged children went to school and also worked part-time in retail. Life was difficult for Samuel as well as for his family since there were many struggles to make ends meet. Yet somehow he and his family managed to survive and avoid hunger or extreme poverty. By the time I met Samuel, he was too old to work but proud of his life and his successful children. He was remained positive yet his words reflected the reality that he was broken hearted and deeply depressed that the ayatollahs had destroyed his life and everything he had worked so hard to create for himself.

Samuel’s story is a difficult one but not unlike the stories of thousands of Iranian Jews and Iranian non-Jews alike who were forced to leave behind their prosperity and easy lives in Iran to escape the evil of the ayatollahs’ regime. Hearing these endless stories of pain, suffering and a true struggle for survival from members of my Iranian Jewish community, compels me to continue speaking out against the Iranian regime today. How does anyone expect us Iranian Jews to remain silent after the hell we endured at the hands of this regime for the last 40 years? How can we remain silent in the face of such anti-Semitism from this regime? How can we remain silent after this radical Islamic regime turned our lives upside down and destroyed our livelihoods? How can we remain silent while this regime continues to call for the nuclear genocide of the Jewish people in Israel and promotes Holocaust denial? How can we remain silent after seeing our grandparents who faced tremendous anti-Semitism in Iran at the start of their lives and then had their lives destroyed again by a radical Islamic regime’s hate for the Jews? How can we remain silent after the radical regime of these evil Iranian ayatollahs essentially uprooted our 2,700-year-old Jewish community in Iran? The deep wounds of the Iranian Jewish community living in America, Israel and outside of Iran following the 1979 will never heal until the current radical Islamic regime in Iran is overthrown and all Iranians can have a chance to live in freedom, tolerance and co-existence with one another.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.