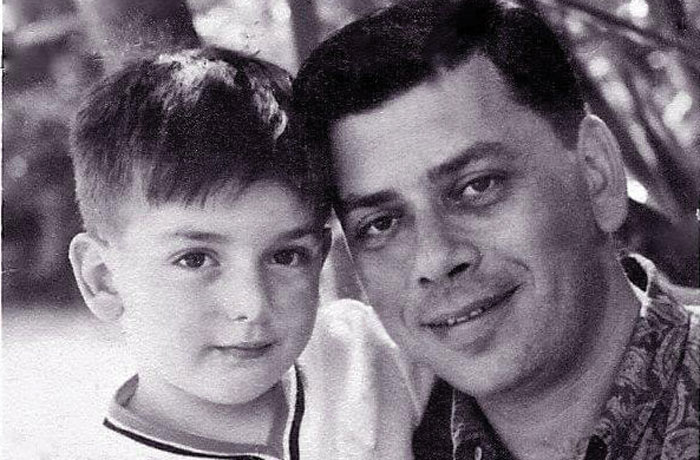

Robert and Jeffrey Sherman

Photo Credit Jeffrey Sherman

Robert and Jeffrey Sherman

Photo Credit Jeffrey Sherman I love Jewish American stories, and last month, a light dimmed on one of the brightest Jewish Americans to ever contribute to this country, and inarguably, the world.

Richard Sherman, who, with his late brother, Robert (1925-2012), wrote some of the most beloved music for motion pictures the world has ever known, died in Beverly Hills at age 95.

I will wager that you know many of the Sherman Brothers’ songs. And I will also wager that you love many of the Sherman Brothers’ songs. Award-winning composer John Williams has rightly described their work as “what we recognize as the American sound.”

That’s because they wrote over 200 classic songs, in particular, for the Walt Disney Company (and several theme parks), including the scores for “Mary Poppins,” “The Sword in the Stone,” “The Jungle Book,” “Winnie the Pooh,” “The Aristocats” and many more.

After Disney died in 1966, “Dick” and “Bob,” as they were known, also wrote the songs for classics such as “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” and Hanna/Barbera’s 1973 adaptation of “Charlotte’s Web.” The duo created more film song scores than any other songwriting team in the history of film.

We, Jews, are an undeniably intellectual people. And while we may relish in sharing news about the latest Jewish Nobel Prize winner, or the latest contribution by a visionary entrepreneur or inventor, we are, at our core, a people of heart. And nothing enters the heart deeper than a truly resonant piece of music. This helps explain why many Jews may not be able to name the most famous Jewish Nobel laureates, but know nearly all the words to “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” from the 1964 classic “Mary Poppins” by heart.

Like many, I believe that the Sherman Brothers were geniuses, whether as lyricists or composers. Their work possessed a rare combination of magic and method; a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it sunshine (Richard) tempered with a slower complexity (Robert) that delighted the child in the grownup and the grownup in the child.

In contemplating this magical, yet methodical genius, consider the somber, yet whimsical playfulness of “Feed the Birds” from “Mary Poppins”: “Though her words are simple and few/Listen, listen/She’s calling to you/Feed the birds, tuppence a bag/Tuppence, tuppence, tuppence a bag.”

“Feed the Birds” was Walt Disney’s favorite song of the hundreds that The Sherman Brothers wrote and produced for him. In fact, Richard’s son, Gregg, told me that at the end of a long work week, on late Friday afternoons, Disney would ask “The Boys” to enter his office on the lot. And, in near Humphrey Bogart-Dooley Wilson fashion, Disney would simply declare, “Play it.” Robert and Richard knew Disney wanted to hear “Feed the Birds.”

Other Sherman Brothers’ songs are even more global. In some ways, “It’s a Small World,” their beloved song written for Disney’s exhibit at the 1964 World’s Fair, can be heard as an anthem for Jewish peoplehood — the kind of peoplehood that inspires a tattooed Argentinian Jew to notice a Star of David necklace and hug a tattooed American Jew as they discover one another at the summit of a Himalayan mountain. “People think it’s a novelty; it’s a prayer for peace,” Richard once remarked about the song.

The Sherman Brothers’ music was particularly meaningful to me after my family and I escaped Iran in the late 1980s. “Mary Poppins” and my favorite film with a Sherman Brothers’ score, “Charlotte’s Web,” were among my first introductions to America and the great American songbook, as heard through motion pictures. In hindsight, Richard and Robert’s music offered me a softer landing as I struggled to find my place in the painfully unknown new reality of my early years in this country.

The Sherman Brothers’ music was particularly meaningful to me after my family and I escaped Iran in the late 1980s. “Mary Poppins” and my favorite film with a Sherman Brothers’ score, “Charlotte’s Web,” were among my first introductions to America and the great American songbook, as heard through motion pictures.

I will never forget the elated wonder that engulfed me in the 1990s when my second- grade teacher at Horace Mann School in Beverly Hills asked each one of us to sit on the musty, carpeted floors and rolled a hefty television on top of a cart to the middle of the classroom. Incidentally, over five decades earlier, Richard and Robert had attended El Rodeo, another wonderful Beverly Hills public school (that’s where Robert met Samuel Goldwyn, Jr. and the two became best friends).

I had recently escaped the fanaticism of post-revolutionary Iran, surviving trauma that included rabidly antisemitic female teachers and administrators; for me, “Mary Poppins” was healing. In fact, it was the answer to the one question I had been too traumatized to ask back in Iran: “Can a female authority figure set boundaries while remaining kind and enabling children to feel safe?”

When I shared this story with Jeffrey, Robert’s son (and Richard’s oldest nephew), he said, “I’m glad that Dad and Dick’s music brought you comfort. That was my dad’s greatest wish.” Based in Los Angeles, Jeffrey and Gregg are both talented writers, producers, directors and composers.

“Charlotte’s Web” is another form of magic altogether. The E.B. White children’s book is beloved in its own right, but who could have imagined that a pig, a spider, a rat and a slew of other animals could inspire some of the most beautiful prose and melodies in recent movie memory? No, between “Mother Earth and Father Time” and “There Must Be Something More,” it’s hard to believe that such sublime music centered on the life and times of a fictional pig in Maine.

“My grandfather, songwriter Al Sherman, agreed with your choice for favorite score, ‘Charlotte’s Web,’ as did my late uncle Bob,” Gregg told me. Al was a Tin Pan Alley songwriter who, during the Great Depression, wrote songs for stars such as Rudy Valee and Eddie Cantor. “My dad and uncle each had an amazing gift and one phenomenal mentor,” said Gregg. “Their dad taught them to write simple, singable, sincere songs that were wholly original. And the brothers were, in my opinion, divinely inspired to create memorable melodies and catchy lyrics that had the ability to click with the audience.”

Fans of “Mary Poppins” will also be delighted to know that Al loved flying kites. Some of the Sherman Brothers’ most well-known songs were inspired by heart-warming reality. “‘Mother Earth and Father Time’ were written for and about my grandparents,” Gregg explained.

It’s no secret that the brothers had a tumultuous relationship, and that’s why it was even more special that cousins Jeffrey and Gregg directed and produced the 2009 Disney+ documentary, “The Boys: The Sherman Brothers Story.”

If you love music, I recommend watching the documentary, and using the rewind button to marvel at the real-life story behind “A Spoonful of Sugar” from “Mary Poppins.” When I asked Jeffrey whether he had a favorite Sherman brothers’ song, he said, “I love ‘Spoonful of Sugar,’ since I inspired it, and “River Song” from “Tom Sawyer” — Dad wrote it for me.” Gregg’s favorite songs were too numerous to list and “they seem to rotate,” but they include “River Song” and “If’n I Was God” from “Tom Sawyer.”

Richard and Robert’s music was at times so whimsical that it’s hard to believe that Robert had been witness to the worst atrocity in human history. At age 17, during World War II, Robert begged his parents to let him enlist, and subsequently served in France, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and Germany. He was shot in the knee by a machine gun.

But the most extraordinary aspect of his service was that Robert Sherman, the man who gave us such songs as “Let’s Go Fly a Kite” and ”There’s A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow,” was among the first American soldiers to enter and liberate the Dachau concentration camp. According to Jeffrey, his father was the only Jew in his squad. “That experience and all those he had from D-Day on,” said Jeffrey, “made him feel hope for humanity was in human kindness and tolerance.”

Robert Sherman, the man who gave us such songs as “Let’s Go Fly a Kite” and ”There’s A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow,” was among the first American soldiers to enter and liberate the Dachau concentration camp.

Regarding Dachau, Robert once said, “It was enough nightmares for the rest of my life.” Upon returning home, he began painting to “get rid of the thoughts of Dachau. Beautiful things helped clean my soul of the horror. But the horror lasted a long time.”

I asked Jeffrey whether his father ever spoke of Jewish identity, and if Judaism was practiced in their home. “Yes,” he said. “Mom was more religious growing up than Dad. I shared that with her. Dad honestly stopped believing there could be a God after he witnessed what he did liberating Dachau. He loved the Jewish traditions and culture though.”

Regarding Richard and his ties to Judaism, Gregg said, “While my dad was not particularly religious, he was profoundly spiritual. He believed doing what you love and loving what you do was his little secret to living long and well. And Dad had a spectacular life.”

After moving to London in 2002, Robert donated two of his paintings to the Western Marble Arch Synagogue, in memory of his late wife, Joyce, who passed away a year earlier. Each painting depicts an elderly Jewish man.

I also could not resist asking Gregg and Jeffrey whether “The Boys” ever experienced antisemitism in Hollywood. “They did not,” said Jeffrey. “In fact, for all the nasty things said about Walt Disney on this topic, they would angrily defend Mr. Disney.”

Photo Credit Gregg Sherman

But Gregg believed his father and uncle did experience the world’s oldest hatred: “Unfortunately, antisemitism was consistently a factor in many of their business dealings throughout their career,” he said. But Gregg also agreed with Jeffrey: “A rare exception was Walt Disney, who is often falsely labeled as being antisemitic, but was not. My dad and uncle were the only staff songwriters in the 100+ year company history and I can assure you, as he told me many times — Walt loved all people. His only criteria for his employees were creativity and positivity.”

While there was nothing funny about the personal tension between the brothers, I like to imagine an almost Talmudic air to how they disagreed over their creative output. In the Disney+ documentary, Jeff Kurtti, co-editor of “Walt’s Time: From Before to Beyond,” a 1998 autobiography written by Robert and Richard said, “The crucible of creativity for these guys is conflict.”

Like most conflicting relationships between Jews, new and better ideas emerged. “My cousin, Jeff, speculated in our documentary that their friction helped bring over a thousand songs to life,” said Gregg. “And while their differences certainly played a part, along with their stereoptic views of the world fueling their songs’ memorable qualities, I would say their similarities also played a huge role in their success: they both absolutely knew when they’d struck musical gold. They pushed each other to remain at their creative peak and the true miracle of the Sherman Brothers was how they continued working together for over five decades.”

Jeffrey also captured the power of this creative tension by observing, “If you agree on everything, there’s no need to collaborate.”

For a new generation of songwriters and composers today, the brothers showed that two creative minds may have a hard time tolerating one another, but still collaborate together to produce extraordinary works of art. And, above all, that creative endeavor requires a near-obsession with ideas.

The Sherman brothers were idea men. Before there were any lyrics or music, the idea came to them. For their brilliance, they were awarded multiple awards, including two Academy Awards (from a total of nine nominations), three Grammy Awards, five Golden Globe Awards and 23 gold and platinum albums. The brothers also have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. “Keep singing their songs and sharing their hope and prayers,” Jeffrey told me.

“I have always been impressed with both their talent and their graciousness on and off stage,” Gary S. Greene, Founder-Conductor of the Los Angeles Lawyers Philharmonic, said. “The Sherman brothers were the most delightful people.” Greene’s friendship with the brothers dates back to the early 1960s, when Richard and Robert became honorary members of the Jr. Philharmonic Orchestra, founded by Greene’s late uncle, Maestro Ernst Katz (Greene was concertmaster of the orchestra for nearly four decades).

Greene recalled one particularly memorable moment: “At one concert around 1964, Richard and Robert told the audience, ‘You are about to hear a song that no one has heard before, but it will become very popular.’ Richard sat at the piano and Bob sang the lyrics. Together, they performed ‘It’s A Small World.’ At the time, I was excited to be present at this special debut and honored to be one of the first to hear a song that soon became a world phenomenon.”

On several occasions, Richard appeared with and conducted the LA Lawyers Philharmonic. In 2018, they held a special performance for Richard’s ninetieth birthday. On June 22, the LA Lawyers Philharmonic is dedicating a special concert at Disney Hall to the memory of Richard Sherman.

“Every night before I put my kids to sleep, they ask me to play ‘It’s A Small World’ as I twirl them in a swivel chair,” Debra Kaiser, Gary’s daughter, told me. “It’s now our family tradition.” As a child, Kaiser played violin in the Jr. Phil as Richard conducted “Mary Poppins” and “It’s A Small World.” The families were so close that Richard even attended Kaiser’s bat mitzvah and her wedding.

In 2013, Disney brought the making of “Mary Poppins” to life with “Saving Mr. Banks,” starring Tom Hanks and Emma Thompson (B. J. Novak played Robert and Jason Schwartzman played Richard.) One of the most endearing stories related to “Mary Poppins” is found in Jeffrey and Gregg’s documentary: In the early 1960s, Walt Disney asked the brothers, “You know what a nanny is?”

Robert responded, “Yeah, a goat.”

“No, no, it’s a British nursemaid,” Disney corrected him. And the rest was the stuff of movie magic.

It’s tempting to imagine the souls of Robert and Richard, fully reconciled, embracing one another and playing heavenly pianos today. Gregg left me with a deeply poignant thought when he said, “The truth about my dad and uncle, Richard M. and Robert B. Sherman is: Deep down, they loved each other – even if they didn’t like each other that much.”

For more information on the June 22 concert honoring Richard Sherman at Walt Disney Concert Hall, visit lalawyersphil.org

Tabby Refael is an award-winning writer, speaker and weekly columnist for The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Follow her on X and Instagram @TabbyRefael

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.