Discussing how best to create an exhibition chronicling the experiences of African Americans during World War II, the staff at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans knew their archives wouldn’t be sufficient. They needed personal stories and, whenever possible, items to accompany those stories.

“I think a lot of African Americans did not see themselves in our exhibit or in the museum, and this certainly was an attempt to change that in a large way,” Kimberly Guise, assistant director for curatorial services for the museum, told the Journal. “A lot of the work was gathering materials, gathering stories and artifacts.”

That call was answered, and the exhibition “Fighting for the Right to Fight: African American Experiences in World War II” was mounted at the museum in 2015. After completing its run in New Orleans, it was reconfigured as a traveling exhibition that has been staged at museums across the country and is now in Los Angeles at the Museum of Tolerance (MOT) through May 6. It’s the first showing in California.

The synergies between the exhibition’s messages and the Museum of Tolerance’s mission are numerous, MOT Director Liebe Geft told the Journal. “As Simon Wiesenthal said, ‘Freedom is not a gift from heaven. You have to fight for it every day,’ ” Geft said. “We don’t take our democratic freedoms for granted and we’re very mindful in this museum — both in the Holocaust exhibit and in the Tolerance Center — how long fought and hard won are the battles of civil rights, and how constant and vigilant we must be in our protection of human rights.”

“We don’t take our democratic freedoms for granted and we’re very mindful in this museum — both in the Holocaust exhibit and in the Tolerance Center — how long fought and hard won are the battles of civil rights, and how constant and vigilant we must be in our protection of human rights.” — Liebe Geft

Civil rights were put to an extreme test when America went to war. Despite the prevalence of racism, discrimination and practices of segregation that existed in the 1940s, the country needed men for the war effort. President Franklin Roosevelt created an executive order banning racial discrimination in hiring practices in industries that held government contracts related to national defense. As a result, African Americans were permitted to join the armed forces and more than 1.4 million of them signed up to serve a country that proved to be not particularly grateful for their contributions.

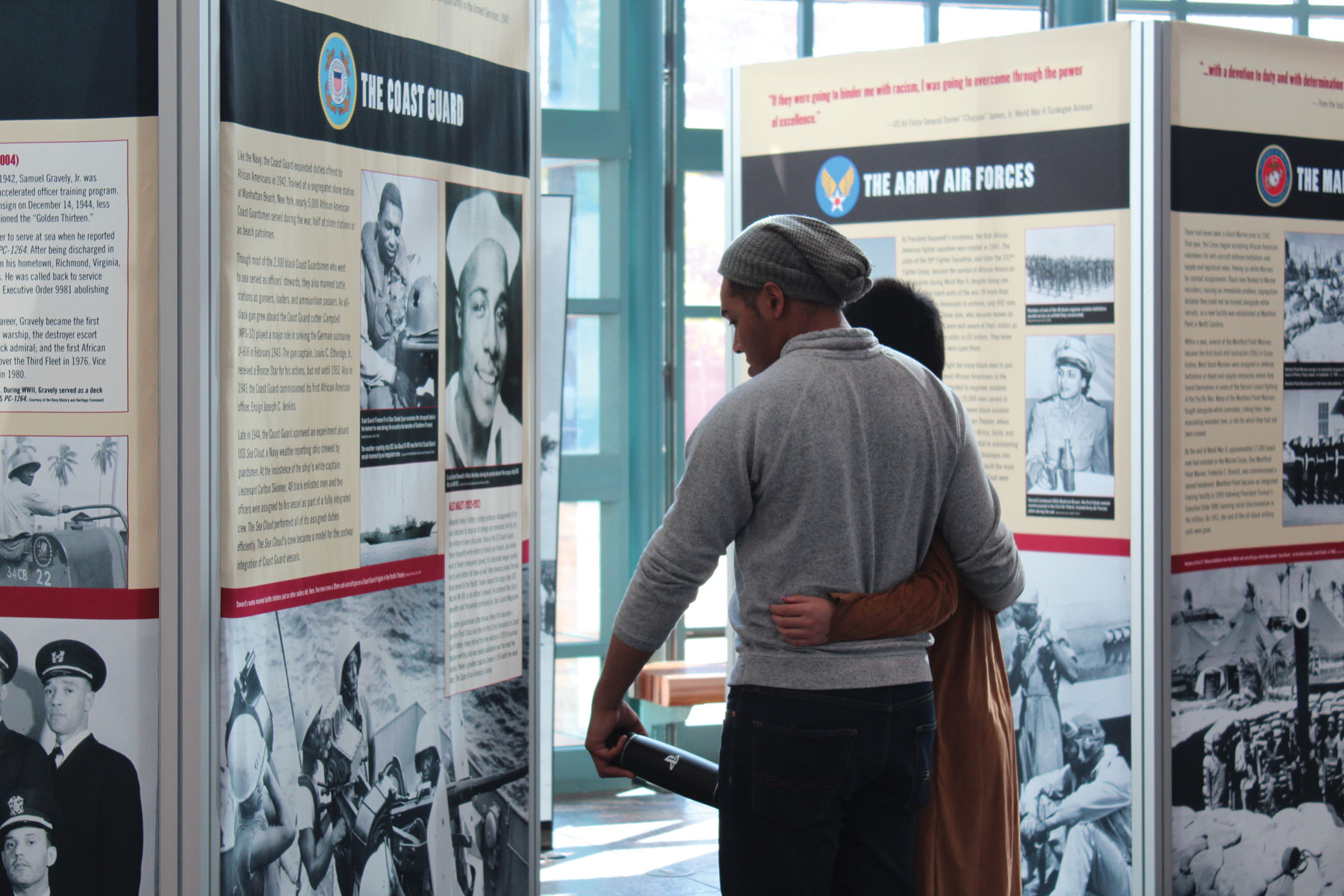

Through informational panels and oral accounts, “Fighting for the Right to Fight” details the landscape that African Americans faced before the war, in all branches of the military during the war and the struggles they encountered on the homefront after it ended. The nation needed manpower to fight the war, but black soldiers were admitted begrudgingly, often refused advancement and subjected to many of the same discriminatory practices in the military that they faced in civilian life. In 1948, President Harry Truman issued an executive order that fully integrated the armed forces, but wounds — both physical and psychological — were slow to heal.

“There was a lot of hurt and bitterness over the treatment they received,” Guise said. “Imagine returning home after having served your country and not being allowed to walk into a store on Canal Street — the main street in New Orleans — to try on and buy a suit. That’s a story that I heard directly from a friend of mine who is a veteran. I think that hurt about that experience led many to not want to save their memorabilia.”

Los Angeles resident Allene Carter also has a story about an African American officer who served during World War II: her father in law, Staff Sgt. Edward Carter Jr. It’s a story she has been trying to tell for more than 20 years and it has a place in “Fighting for the Right to Fight.”

A career noncommissioned officer, Carter had fought as a volunteer in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War and enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1941. At the height of his military career, he served with Gen. George Patton’s Third Army in the “Mystery Division” of blacks, serving as one of Patton’s personal bodyguards. On March 23, 1945, near Speyer, Germany, Carter’s troop sustained heavy casualties and Carter was wounded five times, but he still managed to kill six enemy riflemen and capture two others, obtaining valuable information about enemy positions.

Carter received the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart but was passed over for the Medal of Honor. A damning report from 1943 falsely suggesting that he had ties to communism effectively ended his military career. Carter was honorably discharged in 1949 but was barred from reenlisting.

“He suffered from shrapnel in his body every day and he didn’t know why his country had betrayed him by not allowing him to serve any longer with no explanation,” said Allene Carter, who never knew her father-in-law. “He died at 47 not knowing, and I think he died of a broken heart.”

She wrote the book “Honoring Sergeant Carter: Redeeming a Black World War II Hero’s Legacy,” which allowed him to be reinterred with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1997, President Bill Clinton awarded Carter and six other African American World War II soldiers with the Medal of Honor, the highest possible military honor.

Since Allene Carter had traveled with the families of the other six recipients, she offered to help with outreach when the National World War II Museum approached her about creating “Fighting for the Right to Fight,” which was able to gather and display five of those seven medals at the original exhibition. “Today” show personality Al Roker produced a documentary segment and joined the families of the seven honorees. Two of the Medals of Honor — including Carter’s — have traveled with the exhibition and are on view at the Museum of Tolerance.

“Originally, the World War II Museum wanted me to travel with the exhibition,” Allene Carter said. “But I said, ‘No, I can’t make a career out of following this around.’ That can be pretty grueling.”

“Fighting for the Right to Fight” runs through May 6 at the Museum of Tolerance.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.