The #MeToo movement has jump-started crucial conversations about sexual harassment and sexual violence in the contemporary world — and in the Jewish community. Historical and literary perspectives help us make sense of the present moment. After all, Jewish girls and women — like any girls and women — have experienced sexual harassment and sexual violence through time, in all contexts that Jews called home, from Eastern Europe to North Africa.

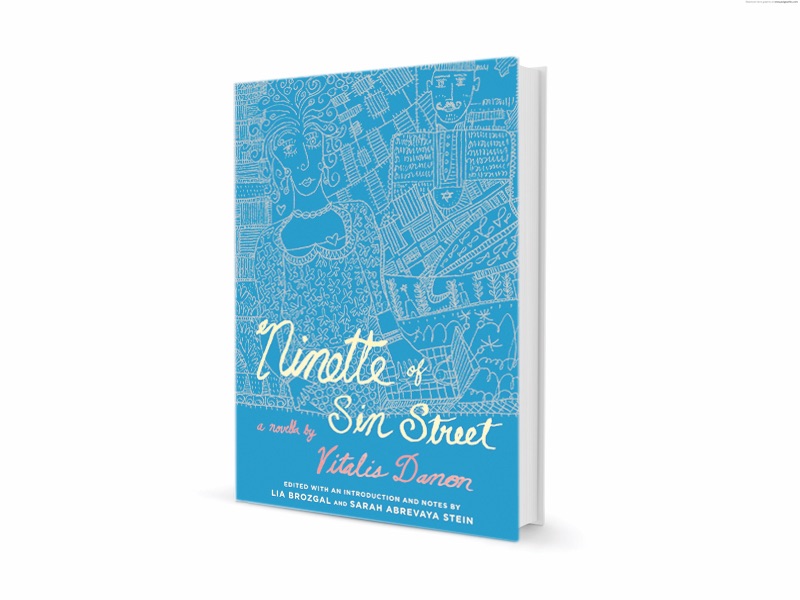

Rape is a lived experience for the protagonist in “Ninette of Sin Street,” a novella originally written in French and published in Sfax, Tunisia, in 1937 and recently republished in English. The story is told in a series of monologues by Ninette, who describes her life frankly — although not without difficulty and shame — to the principal of her son’s school. Ninette, we learn, is an unwed mother who was born into a life of abjection: She grew up in the “ladies’ quarter” (or red-light district) in Sfax, where she lived in poverty, cleaned rooms and did laundry for a few coins, dreaming of “a little apartment on the Avenue (with) fine bed linens,

and gowns, and draperies.” Feisty and witty, she pulled herself up by her

proverbial bootstraps after a rough childhood during which she was thrust out

of the house, scarcely an adolescent and an orphan.

The first disaster came at the hands of someone she knew well, a sweet-talking musician. When Ninette tries to reconstruct the story, it is jumbled in her mind, like a shakshuka, the egg dish that is a staple of Tunisian cuisine. She remembers being offered grilled meat and wine so sweet it seemed like miracle. She remembers finding herself in a hotel room, on a bed, her head so fuzzy she can’t find her way up and out. There is music playing, a man talking. When Ninette wakes, her head throbs, her body is sore and blood coats her thighs. The man who took advantage of Ninette? “I’ll answer the way the rabbi taught me to,” she says, “may his name and memory be forgotten.” But she names him, too, in this early moment of #MeToo: “He was my uncle. And I was thirteen years old.” The rabbi called this Ninette’s “first sin.”

Ninette’s abuse comes in a most intimate form: She is betrayed by her own.

The second fall comes, indirectly, at the hands of a rabbi from the island of Djerba, the spiritual center of Tunisian Jewry about 180 miles south of Ninette’s home. Ninette had turned to the rabbi in desperation, with no money, no job prospects and not even her honor intact. (In addition to her “first sin,” Ninette was obliged to turn tricks to make ends meet.) The rabbi found her what seemed like a perfect job: Ninette was to keep house for a wealthy Jewish matron and her son. It was honorable work for “distinguished people,” pillars of the community, according to the rabbi. But the mother is often gone from the house and the son is bored. More to the point, the son can’t keep his hands off Ninette;

everywhere she turns, there he is: pinching, grabbing, wheedling … until she can resist no longer. Soon, she will be pregnant with his child, and out on the

street again.

Ninette’s abuse comes in a most intimate form: She is betrayed by her own — first by her lecherous uncle, a second time by the rabbi who delivers her into a wolf’s lair and then refuses to stand by her when she emerges, bitten, and a third and final time by her employer’s son. Adding insult to injury, the rabbi and the wealthy matron use Ninette’s sordid past against her, assassinating her character for having sex out of wedlock.

Today, we might read “Ninette of Sin Street” as an early version of a “victim impact statement” or as a form of therapy for a Jewish woman who was also a survivor.

Resilient to the blows that have rained upon her, Ninette narrates her own story, using words that make sense to her, relying on images and euphemism to convey things that are shameful, embarrassing, “bitter memories” that she turns over “all day, all night.”

“Ninette of Sin Street” was written by a Jewish author named Vitalis Danon, who was among the first of a wave of writers to produce French-language literature in Tunisia, when the country was as a protectorate of France. Danon hailed from the Ottoman Empire but came to Sfax as an employee of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a Franco-Jewish philanthropic organization that created secular schools for Jewish boys and girls across the Middle East and North Africa.

We don’t know whether Ninette is Danon’s fictitious creation, a real woman who shared her tale of woe or a composite figure based on the many tales of poverty and abuse he heard from his students and their families. What’s striking is that Danon allowed a poor North African Jewish woman with a tainted past to tell her story and to name her persecutors.

Today, we might read “Ninette of Sin Street” as an early version of a “victim impact statement” or as a form of therapy for a Jewish woman who was also a survivor. As we embrace the bravery of today’s women who announce #MeToo — and if we strive to listen to their stories — let us listen to the world’s historic and literary Ninettes at the same time. n

Lia Brozgal is associate professor of French and Francophone Studies at UCLA, where she specializes in the literature and history of France and North Africa.

Sarah Abrevaya Stein is a professor of history and Maurice Amado Chair in Sephardic Studies at UCLA.