Nicole, the American woman at the center of a crisis of faith in Israel’s highest religious authority, is now a Jew twice over.

Her mother is not Jewish, but the woman — who has appeared in the press and court documents only by that name — told The Times of Israel she grew up attending Chabad and considering herself a Jew, like her father.

She knew, though, that when she wanted to marry her Israeli-born fiancé, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, the body in charge of marriage, divorce and conversion there, would not consider her Jewish, so she converted to Judaism under the guidance of Rabbi Haskel Lookstein, a Manhattan rabbi who commands the respect of the Modern Orthodox movement.

Then, last month, Nicole was told by the Supreme Rabbinic Court of Israel that her May 2015 conversion by Lookstein was not valid, a decision that shocked the Jewish world. In order to marry, she underwent another conversion, this one abridged, in Israel.

The proxy battle for Nicole’s Jewish soul has been a damaging one for the Rabbinate, revealing that only three rabbis in California and 29 in the United States appear eligible to perform conversions that will be valid in Israel. What’s more, conversions even by those rabbis are not assured, depending on whether their names are on a secret list that may or may not exist.

There’s also a celebrity connection: Lookstein also converted Ivanka Trump, the daughter of Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and currently, perhaps, the country’s most famous Jew by Choice.

“[Nicole] was humiliated, but she’s able to get married,” said Rabbi Seth Farber, the head of ITIM, the Jerusalem-based religious freedom organization that represented Nicole before the Rabbinate. “She got where she needed to be.”

However, the slight to a leading Modern Orthodox rabbi by Israel’s highest rabbinical authority has shaken the Diaspora’s trust in the Rabbinate to rule on some of Judaism’s deepest questions, like who is a Jew, and who gets to decide who is a Jew.

Nicole’s struggle with the Rabbinate was extreme but not unprecedented. Many Orthodox Jews by choice, including some in Los Angeles, have similar tales of confusion and frayed nerves.

American immigrant Nicole and her Israeli fiancé, Zohar. Engaged in April 2016, their marriage was put on hold until the Israeli rabbinate accepted Nicole’s U.S. Orthodox conversion.

American immigrant Nicole and her Israeli fiancé, Zohar. Engaged in April 2016, their marriage was put on hold until the Israeli rabbinate accepted Nicole’s U.S. Orthodox conversion.

Esther lives in the Pico-Robertson area with her Israeli-born husband and three children. She wears long skirts, speaks fluent Hebrew and has mastered the use of a fedora as a head covering when she goes to synagogue.

But in 2005, she was a prospective convert looking for answers. She and her husband, whom she’d already legally married, had been sleeping for months in separate bedrooms of their West Hollywood apartment. A rotating shomer, or guard, drawn from among a group of friends who volunteered to sleep on their couch, made sure they adhered to the separation mandated by the strict process of Orthodox conversion.

At some point, it began to dawn on the couple that to get a marriage certificate in Israel — which is what they wanted — the rabbi supervising Esther’s conversion, Zvi Block of Beis Midrash Toras HaShem, might not cut it for the Rabbinate, whose standards they were having trouble discerning.

They’d heard of other rabbis who claimed they could vouch for her Jewish status, but weren’t sure who to trust.

“There was a lot of weird alternatives that we could have gone through,” Esther, who also asked that her real name not be used to protect her privacy, told the Journal. “But it just didn’t sound right, and it didn’t sound legit. We wanted to make sure the way that we did it is totally legit, because it’s going to affect our kids. I want my kids to be able to marry whoever they want to marry.”

After she immersed herself in the mikveh, or ritual bath, she considered herself a Jew and thus bound by the modesty code of shomer negiah not to touch any man who was not her husband by Jewish law — including the man to whom she was civilly married.

“All of a sudden, that momentum crashed to a halt,” she said of the spiritual journey that had been accelerating through the process of finding a congregation and adopting Jewish customs.

She and her husband had arrived at a frustrating sort of nuptial limbo: They wanted badly to marry under Jewish law in Israel, but couldn’t get a clear answer on whether their conversion would be accepted. But as it happened, a cousin of her husband’s friend worked in a regional branch of the Rabbinate and was able to help.

He faxed them a list of names in Hebrew and English. He told them the list was a secret, for their eyes only, and if anybody asked, it didn’t come from him.

“ ‘Nobody knows this, but this is a list of the rabbis the Rabbinate recognizes to do conversion in the United States,’ ” Esther said the bureaucrat told them.

Sitting at her dining room table with a blue folder in front of her that contains documents related to her conversion, Esther pulled out four pages she said the man faxed her with the names, addresses and telephone numbers of a list of U.S. rabbis.

Their suspicions were confirmed: Block, their L.A. rabbi, was not on the list.

A few months later, Esther and her husband were on a plane to Monsey, a hamlet in upstate New York with a large Chasidic population, where a local rabbinical court performed her conversion. Shortly after, the two were married in Israel.

Whether or not such a list even exists is a topic for debate. The Rabbinate has flip-flopped on its existence, a crucial point in an ongoing courtroom drama with ITIM: The nonprofit sued the rabbinate in an attempt to compel it to release a list of rabbis approved to perform conversions abroad.

Block, for one, said he’s gotten conflicting messages from Rabbinate officials on whether a list exists, and whether he’s on it if it does.

“ ‘Yes, you’re accepted; no, you’re not accepted. Do this, do that,’ ” he said on the phone with the Journal, imitating the rabbinic functionaries he’s spoken with over the years.

Block said he insists on strict observance among the converts he tutors. But he sees the Rabbinate as approving people based on “political considerations” rather than religious ones.

“To be perfectly honest, I think the Rabbinate is a tragedy,” Block said.

Nevertheless, he said, “I know enough people inside the infrastructure to get anybody I convert accepted. They don’t like me because I do that, but I’m committed to the people that I work with.”

ITIM’s lawsuit, which Farber said has “not reached the endpoint,” hopes to reveal who’s on the roster of rabbis outside Israel whom the Rabbinate finds acceptable, thereby removing the guesswork for converts.

The Rabbinate has responded to the suit by claiming no such list exists.

“Rabbis are not approved; rather, cases are approved,” the Rabbinate attorneys argued in Jerusalem District Court, The Times of Israel reported. “Personal status requests have been approved based on all the circumstances in the case, not necessarily based on the rabbi’s identity. And at present, there is no list of approved or recognized rabbis.”

In January, the court ordered the Rabbinate to release a list of rabbis whose conversions have been accepted in the previous six months. The list, published some three months ago, included only three rabbis in California — Avrohom Union, Shmuel Ohana and Avraham Teichman — all of them in Los Angeles.

The list also came with a waiver, Farber said: “ ‘Just because we approved them in the past doesn’t mean we’re going to approve them in the future.’ ”

Despite the revelation, the Rabbinate walked away effectively denying the existence of a second, master list.

But when Nicole’s case came before the Supreme Rabbinic Court on July 13, Farber said he was shocked to learn that their reason for rejecting her conversion was because Lookstein is not on a list of approved rabbis.

“We’ve been in court a year and a half and they claim there is no list,” he said, his voice rising over the phone from Israel. “Now you’re saying Lookstein is not on the list. … You must be joking!”

The decision to repudiate Nicole’s conversion raised condemnation from Diaspora leaders, such as Natan Sharansky, head of the Jewish Agency for Israel, who saw it as an insult to religious leaders outside the Jewish state.

The idea of certifying individual rabbis from an office in Jerusalem to perform conversions is a prickly one for some observers.

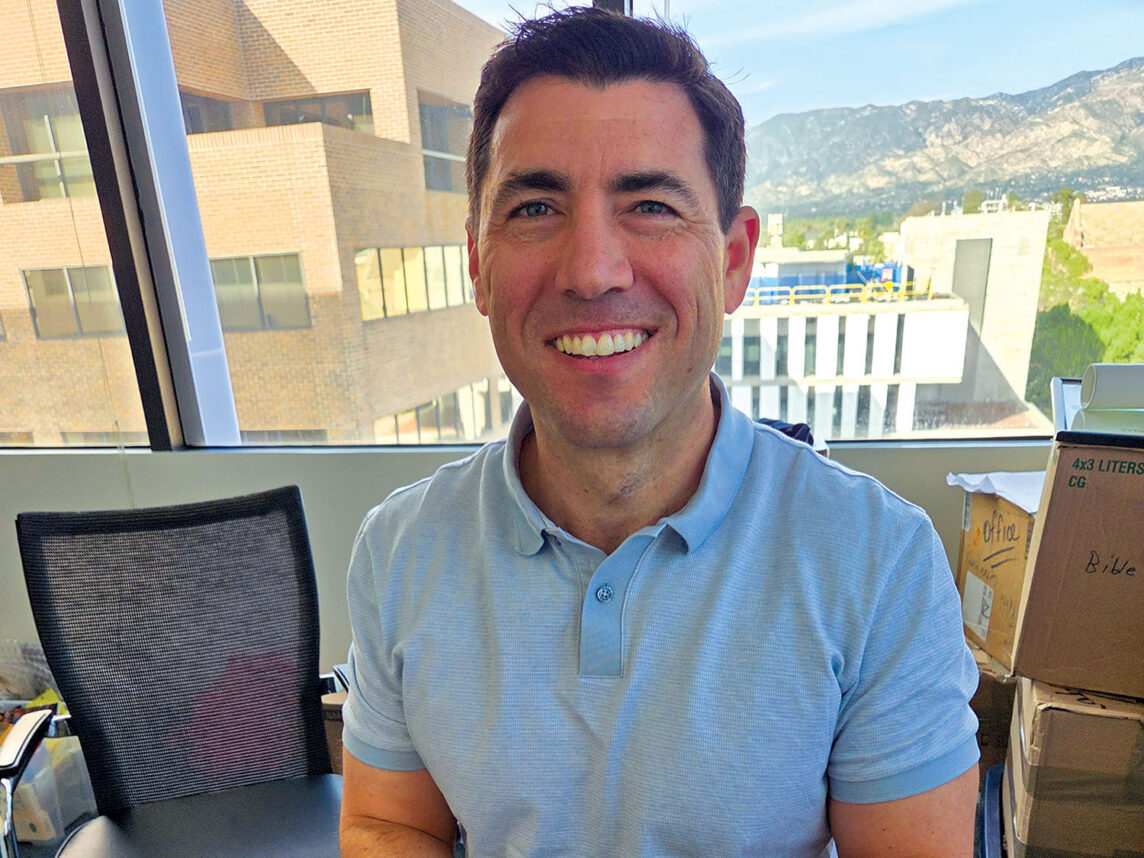

“Once you’re imposing a list upon the entire Jewish people and the entire State of Israel — there’s no halachic [Jewish law] basis for that, and it’s really an innovation, a very destructive innovation,” said Rabbi Shmuly Yanklowitz, a leader of the open Orthodox movement in Scottsdale, Ariz., who converted twice, once with a liberal rabbi and then again as an Orthodox Jew.

Yanklowitz said he has had his identity as a Jew challenged on several occasions, a singularly wounding experience. By allowing converts to be humiliated at the highest reaches of the Jewish law courts, he said, the Rabbinate alienates the Diaspora and creates a less inclusive Judaism.

“There’s a prohibition in the Torah to [not] oppress or shame converts, and I think that we’re violating that,” Yanklowitz said.

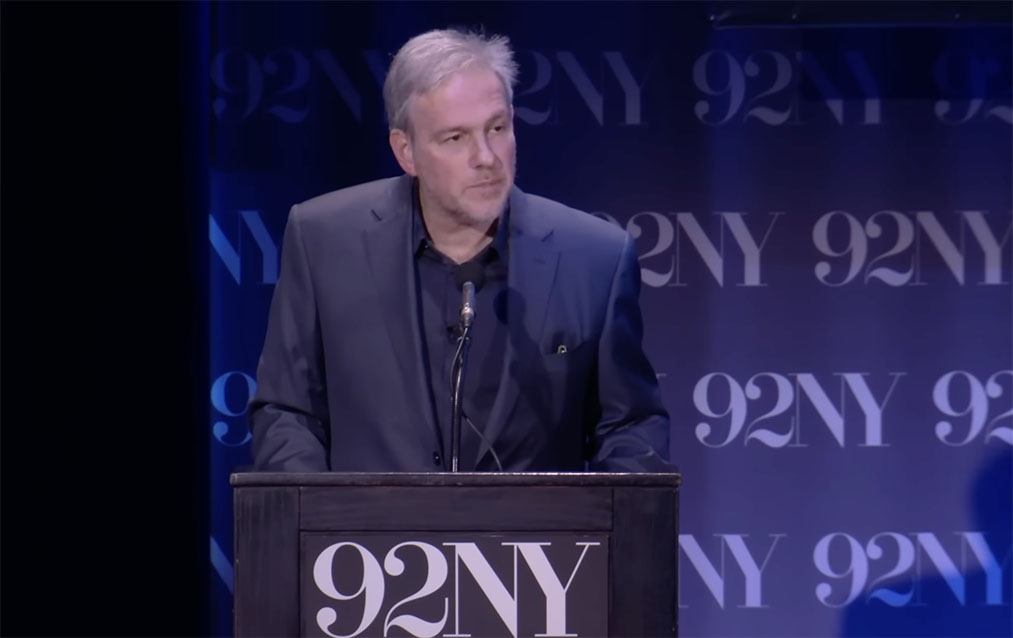

Farber suggested the Rabbinate could demystify the process by [collaboratively] identifying certain Orthodox institutions — the Orthodox Union (OU) or the Rabbinic Council of America (RCA), for instance — whose members would automatically be able to vouch for a person’s Jewishness before the Rabbinate’s marriage registrars.

The problem, he said, is that a system is only as good as the rabbinate that enforces it.

The Chief Rabbis’ office vouched for Lookstein to the Petah Tikva beit din, or Jewish law court, where Nicole initially sought to have her conversion approved, but the local court effectively ignored them.

When her case came before the high religious court, the two Chief Rabbis — one Ashkenazi and the other Sephardic — could have assigned themselves to the three-person bench reviewing the case, but they didn’t.

The Chief Rabbinate didn’t respond to an emailed request for comment on this story.

In practice, the Rabbinate entrusts the RCA with some authority on the conversion process in the United States. Rabbi Michoel Zylberman, director of the RCA’s Geirus Policies and Standards (GPS) program, is on the list published by ITIM.

So is Union, who runs the beit din of the Rabbinical Council of California (RCC), an RCA affiliate.

Asked if he was aware of such a list, Union said in an email that not only does he know of it, but has long been a member in good standing.

“The list is not new,” he wrote. “We have been on it since 1989, when our beit din was organized. What’s new is that Rabbi Farber is publishing it (not that there is anything wrong with that). In the past it was an internal list used by the batei din in Israel for guidance, since they obviously know very few of the rabbis outside of Israel.”

The RCC’s status applies to only the court it runs, which consists of Jewish law experts, and not to all of its member rabbis, he wrote.

“Rabbis who are members of the RCC cannot perform conversions or gittin [divorces] … Private Giyur [conversion] etc. is neither authorized nor accepted,” he wrote.

Shmuel Ohana is an RCA member but performs conversions on his own authority, through Beth Midrash Mishkan Israel, a Sephardic congregation in Valley Village. Ohana’s name is also on the list.

He told the Journal he has close ties with the Rabbinate, in particular with Itamar Tubul — the functionary who corresponds with local marriage registrars about which rabbis are of good standing, and who plays a part in the ITIM suit.

“My conversions for the last 10 or more years have been accepted in Israel with no questions,” Ohana said.

He believes the Rabbinate accepts his conversions because of the rigorous process he adheres to. He said he asks each convert to “sign a paper on the oath of the Torah and on their conscience that they are going to raise their children as Jewish children, keeping all the commandments of the Torah, kashrut, Shabbat, etc.”

Yet Block, the rabbi who performed Esther’s conversion, said there are names on ITIM’s list whom he believes are less strict in their conversions than he is.

“I guarantee you: Anyone that converts with me is keeping kosher and keeping Shabbat and practicing family purity to the best of my knowledge,” he said. “That’s what we require from them.”

He suggested the Rabbinate solve its present confusion by crafting a set of universal standards for Orthodox conversion.

“Here’s what you’ve got to do,” he said. “Send out those standards to every beit din operating in America. Everybody that agrees with them is on your list.”