In a back room of his Echo Park studio, ceramicist and sculptor Peter Shire retrieves a box of mezuzot that he designed. He pulls out one. It consists of a stainless steel tube for the scroll, and on both ends are turquoise and yellow disks fitted with thin rods topped with little red and orange globes, like a crown. It’s a humorous and playful object, and a far cry from traditional Judaica.

“What we regard as serious, really, most of the time, is solemn and decorum and not real feeling,” Shire said. “There’s no harder work than play and, you know, being in the moment.”

He designed menorahs with the same eclectic approach, which Shire links to his Jewish background.

“Making a joke is a great way to get at the truth, maybe without getting people too upset,” he said.

A survey spanning four decades of Shire’s similarly whimsical teapots, tables, chairs, cabinets and other creations is on display at the MOCA Pacific Design Center in West Hollywood through July 2. “Peter Shire: Naked Is the Best Disguise” is his first design survey at a Los Angeles museum.

His works include everything from silverware, plates and cups to T-shirts, sculptures and paintings. The MOCA show also includes sketches and engineering plans that illuminate his design process.

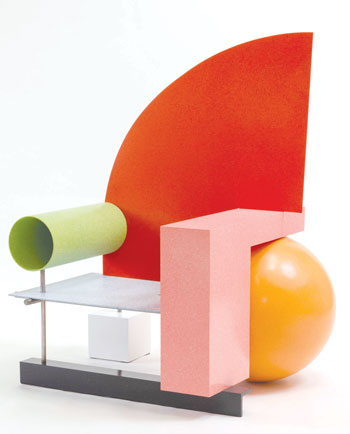

“Naked Is the Best Disguise” is a swirling mashup of color and geometry, with smoothly finished shapes jammed together into works that walk a tightrope between craft and fine art.

“It is a kind of all-encompassing aesthetic possibility for Peter,” said Anna Katz, curator of the MOCA show.

Even the metal cabinets and machines in his studio are slathered in vivid paint.

“There’s a practical reason” for painting his equipment, Shire said. “One is that a lot of them are used, and so they come in pretty beat up and grimy and gross looking. And the other reason is, that’s what I do. I paint objects. I mean, why should they be different than the work itself?”

Born in Echo Park in 1947, Shire even dresses like his sculptures, with striped black-and-white T-shirts and bright mismatched socks. He has a gray beard and a wide, impish grin.

Dig underneath his silliness and he’s trying to make a serious point: Everyday objects meant for daily use are just as worthy of artistic attention.

The teapots stray the furthest from their classic shape and encapsulate Shire’s interest in transforming functional objects into sculptural forms defined more by aesthetics than utility. More than 20 teapots are included in the show.

An advertisement for his work was included in a 1981 issue of the irreverent Venice-based WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing, which drew the attention of Italian designers. That led him to become the only American founding member of Memphis, a design collective based in Milan. Memphis challenged “good taste” and the principles of modern design, such as “form follows function.”

One example of such a defiant sculpture is “Bel Air Chair,” produced in 1981 with Memphis. More a jumble of shapes than a chair, it has a red back, an orange sphere as a foot for the chair and a green cylinder as an armrest. He made a second, deconstructed version in 2010 called “Belle Aire Chair,” and for the MOCA show he made a 2017 iteration called “Brentwood Chair.” In the lastest version, the orange sphere is placed in front of the seat, challenging the definition of a functional chair.

Though he began as a potter, Shire has experimented with metal, glass, painting and large-scale outdoor art. One of his best-known public sculptures in Los Angeles is a 28-foot-tall steel and copper construction that resembles a city skyline. It rests atop Angels Point, the highest spot in Elysian Park, which offers commanding views of downtown and Dodger Stadium.

At his studio in the heart of Echo Park, giant metal sculptures peek out from a parking lot. Large spindly frames hold red, yellow and blue circles and squares, like giant versions of a Joan Miro painting or an Alexander Calder mobile.

The studio was once an auto repair shop, and Shire cites a lifelong love of hot rod culture as an inspiration in his work. One metal sculpture in the studio resembles an engine’s pistons. He also was inspired by California surfing culture, the designs of Charles and Ray Eames, and the midcentury Googie architecture of car washes and gas stations, including Googies, a coffee shop designed by architect John Lautner and formerly located at the corner of Sunset and Crescent Heights boulevards near West Hollywood.

“My parents made fun of it. We’d go past it on the way to the beach. It was kitsch, done by arguably the greatest Southern California architect,” Shire said.

He describes his parents as the type of “effete modernists who had developed, through their heritage, the ideals of art and modernism.” But to Shire, L.A.’s car washes and coffee shops “were fantastic, because they were kitsch. And I will define kitsch my way, which is the substitution of real values for spurious values, i.e., plastic flowers.

“I subscribe to the idea that kitsch is an idea of substituting fake for real. And I think we’re making an attempt to bring that back the other way and bringing the fake back into the real, because we’re not getting rid of the fake, you know. Plastic flowers are here to stay.”

His love of color also comes from his childhood home in Echo Park.

“My father was very color oriented, and he colored our house very carefully with groups of contrasting and complementary colors,” he said. “Colors can make you feel good and they can make you feel depressed.”

Shire is best known for his mugs and handcrafted earthenware, splattered with brightly colored paint and produced since 1972 under the name Echo Park Pottery. Strangers regularly walk into Shire’s studio to gawk at the sculptures and ceramics.

“There’s been this tremendous resurgence of attention to Peter, particularly among young artists in L.A. in the past, say, 10 years,” Katz said. “There are constantly young artists visiting his studio.”

Ben Medansky, a young ceramicist in Los Angeles, moved to Echo Park from Chicago five years ago. He walked into Shire’s studio was offered a cup of coffee and became his

assistant for a summer.

“I’d been following his work my whole childhood and understanding what the Memphis design movement was. … I worked for him for maybe two or three months … but felt like I had learned so much. He was truly a mentor of mine and really inspired everything I do today,” Medansky said.

While rebelling against the strict rules of modernism, Medansky said, the Memphis design movement valued quality work.

“His idea was to always make things fun and cool and pretty. He wasn’t really interested in this new direction of art that really encourages bad aesthetics or bad art or ugly, grungy stuff,” Medansky said of Shire. “I really appreciated the high craftsmanship in all the work.”

Medansky, 29, says the Memphis postmodern design aesthetic underwent a resurgence a few years ago, and while “he might not realize it because he wasn’t on Tumblr or Pinterest,” Shire’s work found a new audience among young artists.

“He understands the camp and the kitschiness of the work that he’s creating,” Medansky said. “It’s very self-aware, and I think the entire Memphis group was self-aware of bad taste and knowing that bad taste can be taken seriously. He’s a big proponent of serious fun.”

“Peter Shire: Naked Is the Best Disguise” is on display at the MOCA Pacific Design Center in West Hollywood through July 2. For more information, visit moca.org.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.