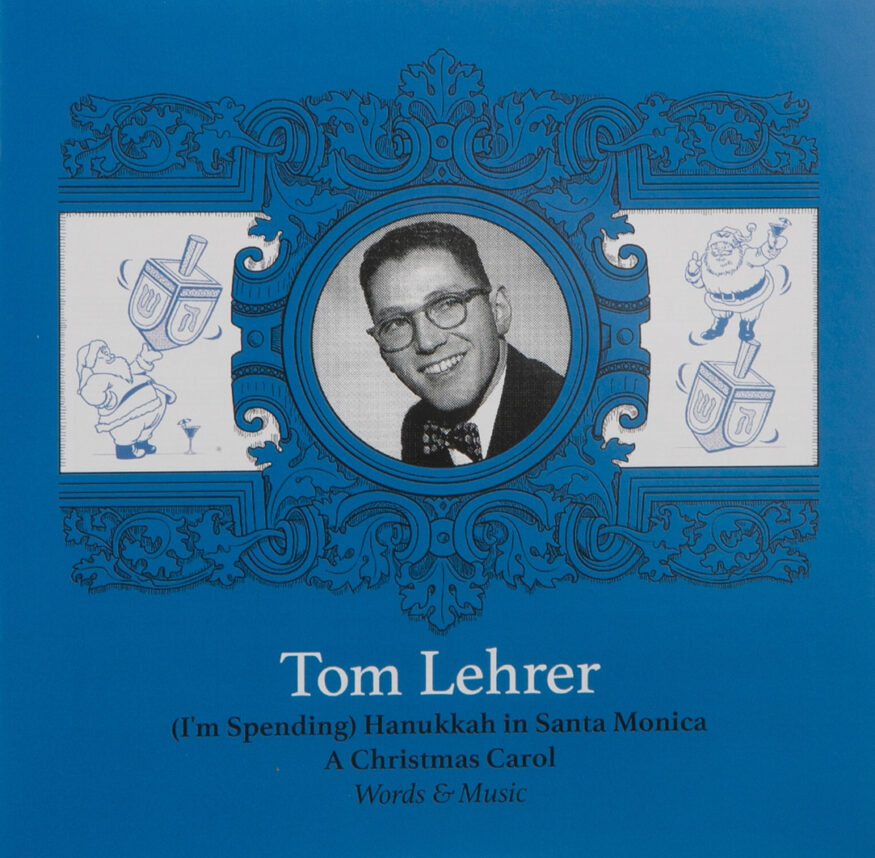

A still from Gary Baseman’s work on the animated Disney movie “Teacher’s Pet.”

There’s an old saying that goes something like this: We spend the first half of our lives running away from home and the rest trying to get back. Consider Homer, way back in ancient Greece, who defined our notion of a life’s odyssey as a journey that begins and ends at home.

The same could be said of Gary Baseman, a Los Angeles artist whose career retrospective opens this weekend at the Skirball Cultural Center. Baseman organized the show thematically, inspired by the rooms of his childhood home — Living Room (Welcome), Dining Room (Celebration), Hallway (Journey), Kitchen (Feast), Bedroom (The Human Condition). All of the artworks are installed alongside actual furniture and artifacts from the house where he grew up, along with some objects from his relatives’ homes. Personal history is an ongoing inspiration for Baseman: He’s currently working on a new series titled “Journey to My Mythical Homeland.”

Baseman is a highly eclectic artist whose very personal iconography recalls such diverse traditions as Rudolph Dirks’ Sunday comic strips “The Katzenjammer Kids”; the underground artist R. Crumb and Raw comics; the haunting psychic landscapes of Picabia and Dali; and the multimedia and multiplatform work of such post-Warholian Pop artists as Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and Takashi Murakami. Baseman does it all — paintings, prints, advertising, commercial illustration, TV series, animated film, toys, wallets, stickers, installations and performances — the sum total of which Baseman calls his “pervasive practice.”

His distinctive style has been consistent since childhood; it features anthropomorphized animals and invented creatures, as well as women and children, all of which are depicted in toy- or doll-like form or transformed into mythical creatures. Many of the images are shown traveling through crowded, dream-like landscapes. At the same time, the creatures and narratives of Baseman’s paintings and various series coincide metaphorically with the artist’s maturation as an artist and with the events of his personal life.

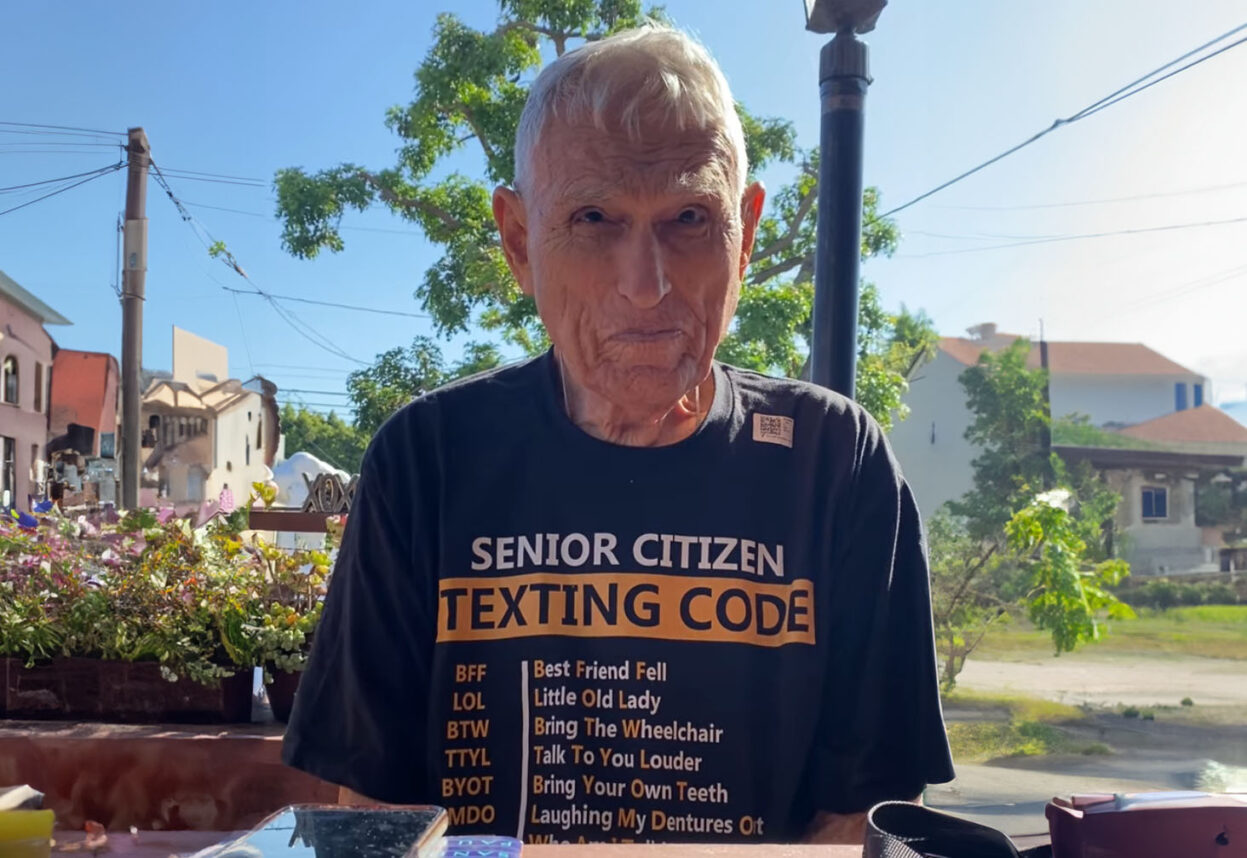

Baseman with pet cat Blackie.

Baseman’s work has been exhibited in museums and galleries all over the world, however Los Angeles is his home, and at the Skirball he really wants to bring his audience into his world, to inspire each visitor to feel at home with all his artistic creations.

When I visited him recently at his Los Angeles studio and current home, Baseman welcomed me with Old World manners into his repository of obsessions and collections — a deluge of toys, photos and advertising artifacts from the 1930s and ’40s worthy of the Collyer brothers as well as a treasure trove of his art in various stages of completion. We talked for two-and-a-half hours, and the conversation easily could have lasted many hours more.

Baseman’s parents met in a displaced persons camp after World War II; both are originally from towns in what was then Poland (now Ukraine) outside of Rovno (Rivne). His father, Ben, escaped from his town, Berezne, into the nearby forests, and fought with a Russian partisan unit; Baseman’s mother, Naomi, survived because her city, Kostopol, fell under Soviet domination.

The artist was born in 1960 in Los Angeles; he’s a full decade younger than his siblings and the only native U.S. citizen in the family (his brother Morris was born in Austria, brother Sam and sister Netta in Canada). Baseman was, he said, his parents’ “American Dream” baby — the one who could grow up to become president. Although his parents and most of their friends were Holocaust survivors, they didn’t want to burden him with their past. Yet as he was told on childhood trips to Israel — one at age 4 with his mother, the other at 12 with his father — the reason his parents had survived so much, the reason they worked so hard and even the reason Israel was founded, was all for him.

He was the hope of the next generation. No pressure. All he had to do was excel and succeed.

His parents spoke English with thick accents and spoke Yiddish to one another and to other Holocaust survivors, a language as foreign yet as familiar to Baseman as the Spanish that surrounded him in the rest of his city. His father, an electrician, did not talk much, but when he did, it was of survival and sacrifice, and he inculcated Baseman with the mantra that if you work hard and are a good person, anything is possible. If there ever were a problem, he would say in his Yiddish-accented English, “The door is always open.” Those words became the title of the Skirball exhibition.

Baseman’s mother worked at the bakery counter of Canter’s Deli on Fairfax for more than 40 years, at a time when Canter’s was very much the epicenter of Fairfax’s Jewish district. The family lived in one unit of a four-plex on Curson Avenue, a half block from the old Pan Pacific Auditorium, the Streamline Moderne architectural gem that closed in 1972 and burned down in 1989, but which Baseman cites as having influenced his early aesthetic. When Baseman was 5, the family moved to another apartment a few blocks away, on Detroit Street.

Given that his parents worked long hours, Baseman was a latchkey kid, left mostly to his own devices. He attended area public schools: Third Street Elementary, John Burroughs Middle School — his bar mitzvah was at the Orthodox Shaarei Tefila on Beverly Boulevard — and Fairfax High School. Although he has never had any formal art training, Baseman knew early on that he wanted to be an artist. At 11, he twice won the monthly Bob’s Big Boy art contest, and in 1978 he won the Area E art contest judged by Sergio Aragones of Mad magazine and Stan Lee of Marvel Comics. From Fairfax High, he won the Distinguished Art Service award for illustrating the school newspaper and the yearbook.

He went on to UCLA, graduating from there as a communications major, magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa. He says he was driven to be the “goodest” student, with perfect attendance, great grades — and the most moral, never breaking any rules, even to jaywalk or have a drink before his 21st birthday.

200 Tobys at “For the Love of Toby,” Billy Shire Fine Arts, Los Angeles, 2005. Photo by Gary Baseman

After graduation, Baseman felt the responsible thing to do was to pursue a commercial art career while continuing to make art, “on the side.” He did a short stint at an ad agency, but that did not really agree with him, so he began to pursue work as a commercial illustrator. An image he made for the cover of The New York Times Sunday Book Review put him on the map.

To make his American Dream come true, Baseman moved to New York in 1986. “The advertising and publishing and art world were all in New York,” he said. At the time, he believed, “Every major artist was in New York, and if you lived in L.A. you were a substandard regional artist. You had to go there.”

He became a successful commercial illustrator: “I did 12 to 20 assignments every month for 10 years,” Baseman said. “I didn’t take a lot of vacations; I was really there to work.” The New York Times assignment was followed by Time, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker and Entertainment Weekly. He also created commercial campaigns for Gatorade, Nike and Mercedes-Benz. Baseman won several illustration awards, including the prestigious Art Directors Club award. He was also realizing his own Ralph Lauren-esque transformation, marrying Mary Ellen Williges, a beautiful and stylish All-American girl, and settling in the suburbs.

At the same time, commercial work was increasingly being seen as art, while underground comics and graphic novels were going mainstream. Photographer Robert Mapplethorpe did commercial work, director Tim Burton was making live-action and animated feature films, cartoonist Art Spiegelman won a Pulitzer for “Maus,” and Spiegelman’s wife, Francoise Mouly, the former editor of Raw, became cartoon editor at The New Yorker. The outlaws were becoming the insiders. Illustrators such as William Joyce were doing Disney children shows, and Klasky Csupo’s “Rugrats” ruled Nickelodeon.

Baseman, whose art design is featured on the popular board game Cranium, saw the opportunity and began to pitch TV concepts. He made two pilots for Nickelodeon that never aired, however the experience gave him “the hunger to get a show on the air,” as well as the realization that for TV, “I need to be in L.A.” Which was just as well. Baseman found New York’s weather too severe and life there too harsh — there were some things he could not get over, such as “the smell of urine in the Broadway-Lafayette subway station.”

Los Angeles was more to his liking. He sold a show, “Teacher’s Pet,” which began airing on the Disney Channel in 2000 and became a great success, winning four Emmys, including an outstanding performer win for Nathan Lane. Baseman enjoyed the collaboration with other animation artists and with writers Bill and Cherie Steinkellner, as well as making the “Teacher’s Pet” movie in 2004. At the same time, Baseman was invited to show his art in a serious gallery, the Peter Mendenhall Gallery in Pasadena and to work with Kidrobot to create limited-edition designer toys. Baseman purchased a beautiful home for his wife and himself in Hancock Park.

The American Dream, indeed.

Yet Baseman’s work from this period, from 2000 to 2005, tells a different story. His creatures and landscapes of this period seem unresolved — childlike yet adult, infantile yet serious, at play and yet in danger. His images of females are idealized, asexual objects of veneration. It is an unreal world of arrested teenage development where everything appears OK — in turmoil but devoid of conflict, and where sex does not exist and desire is frightening and held in abeyance.

“I hid in my work,” Baseman said, explaining that there was “a sense of desire and longing and lust in my work, and I felt it was oozing out of me, in my pores, and in my characters … [such as] these ‘infinity girls,’ whose arms and legs entwine like the infinity sign but they are just out of reach. You can’t obtain them.” Baseman’s state of mind at that time is perhaps best revealed by his character “The Happy Idiot,” which, Baseman explains, is “the snowman who’s willing to sacrifice himself for the mermaid, melt himself down so she can live.”

In 2005, Baseman started painting forests and created a narrative about “running into the woods and this creature licking my wounds and bringing me back to life and then devouring me.” He didn’t make the connection at the time, but today he has come to recognize that the forest evokes the place into which his father escaped to survive the war.

Baseman had also created a series of piñata paintings beginning in 2002 in which the characters’ guts are laid bare, literally. These could be seen as showing how Baseman was being torn apart by his inner turmoil. Increasingly, his paintings told the story of a struggle between creatures of what he called “Creamy Goodness” and creatures of desire.

Sketchbook drawing by Gary Baseman, 2012 (Forest Sketch)

In 2005, Baseman introduced his now-signature character, Toby, who looks a bit like a Bizarro fez-wearing Mickey Mouse and whom Baseman claims is his alter ego. Toby began to appear in travel photos — at the Sistine Chapel, with Michelangelo, looking like he is holding up the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Baseman calls Toby “the keeper of the secrets.” Which begs the question, if Baseman was so “good,” what secrets did he have to hide?

Raised to be good and to always see good in the world, Baseman nevertheless had a clear view of hypocrisy, the unhappy lives of suburban America, the corruption of politicians and the deceit of evangelists. Even the Orthodox Jews his father held up as pious were often revealed in the media as having feet of clay. Baseman had come to realize that no one really cared that he had never skipped class in high school, and he found that whatever success he had achieved did not keep him from unhappiness; that suppressing his secret desires, longings and dreams or painting them did not make them go away.

Even harder for him to admit was that maybe these yearnings were good, not bad. Maybe the world wasn’t as his father raised him to view it. Baseman had a hard time admitting all this — or that he was unhappy in his marriage.

In a life where he succeeded at everything he worked at, Baseman couldn’t countenance a failed marriage. Even after separating from his wife in 2006, he couldn’t admit as much to his parents, who only learned of the impending divorce from his wife.

Baseman moved out of his Hancock Park home and into the ground-floor apartment of a Carthay Circle duplex. He continued to avoid confronting his reality by traveling and enjoying being newly single. He was, he now says, literally running away from himself. In his paintings from this era, about 2006 to 2009, his characters are shown traveling through a forest, sometimes carrying rifles. Into this environment appear the new characters, “Wild Girls,” who hold the promise of joy in the moment, without deeper commitment. They, in turn, are beset by little demons suggesting that pleasure is not without its danger.

In 2009, Baseman returned to Israel for the first time in 36 years to teach at the Bezalel Art Academy. While in Israel, Baseman also had a show of his work, which he called “The Sacrifice of Ooga” — ooga (sponge cake) being Baseman’s favorite Hebrew word as a child. His canvases were filled with his “Wild Girls,” who represented Baseman’s own sexual revolution, and other characters called “Chouchous,” who represented the still unattainable bliss and goodness that was complicated by all his demons. In contrast to these creatures representing Baseman’s id, he also created a dragon, his super-ego, a symbol for those parental demands that kept him even from jaywalking.

Baseman knew what had to happen: “I had to sacrifice that dragon, to kill it.” But he was surprised by what he did: “When I got there, I couldn’t slay it.” Baseman said, adding: “I tried in my art, but I’m still working on it [in my personal life].”

I suggested to Baseman that perhaps he could not slay the dragon and free himself of the inhibitions caused by his parents’ expectations because he discovered the dragon was not a creature apart from him — it was a part of him. To wit: In Israel, Baseman found he had come to the end of his running away. Baseman needed to make peace with his past and with himself. The journey, wherever it took him, was now as much inner- as it was outward-directed. It was time to return home.

Although Baseman had confronted the burden of his parents’ dreams, he nonetheless had to face their mortality. In 2010, his father, who’d always had a tremendous will to live, even recovering and thriving after diabetes-related leg amputations, died at the age of 93.

“When my father passed … I realized that I was the keeper of his story, and if I didn’t tell his story, it would be lost forever.” While visiting with some distant cousins in Israel, Baseman learned of the existence of a yizkor (memorial) book from his father’s town that his father had never told him, or any of Baseman’s siblings, about. Baseman wondered why. After his father’s death, he found the book hidden in a container in a closet filled with bills and other papers. The book contained several pages describing his father’s heroism as a partisan.

Video by Eric Swenson

Baseman realized how little he knew about where his parents had come from. “To know those stories, I needed to go there and pay my respects.”

So, last year, Baseman received a Fulbright fellowship to teach at the Art Academy in Riga, Latvia. From there, through social media, he connected with two artist friends who lived in Lviv, Ukraine — Jana Brike and Aigars Bikse — who arranged for him to come to Lviv to speak to art students from all over Ukraine. They also offered to drive with him from Riga to Lviv, and then on to his parents’ towns, outside Rivne.

“It was very emotional … To travel through Warsaw and Lodz, going through Krakow and Auschwitz and going though Lviv and heading through Rovno, and even doing interviews on Ukraine National TV and Lviv local TV, telling my story and also visiting my parents’ towns,” he said.

Today, he said, his parents’ hometowns are very suburban, and there are few traces of the former Jewish life there. Baseman was able to find where his mother’s home once stood, and he walked along the path where her relatives were taken to be murdered and left in a mass grave. In his father’s town, he found the abandoned cemetery where his great-grandfather was buried, but the gravestones had all been taken for use in another building. There was a memorial at the mass grave of his paternal grandparents, and he paid his respects there.

As a personal art project, Baseman had his friends from Lviv print photos of his grandfather and frame them. They nailed them to trees in the cemetery where his grave should be. Baseman put on a costume he had made, of a giant magi with a cone-like head with one giant all-seeing eye, and wearing an apron with the Hebrew word for truth, emet, printed across his chest (emet is also the word that activates the golem). Baseman’s friends photographed him wearing the costume, not only in the cemeteries but also in his parents’ towns. “To let people know there and everywhere that you can’t hide the truth,” he said, and to remind them “that [there are] souls there.”

Which brings us back to the exhibition, organized by Skirball curators Doris Berger, Erin Clancey and Erin Curtis.

During his emotional trip to Eastern Europe, Baseman thought: “I’m going crazy, and this is what my parents were protecting me from. I opened up Pandora’s Box.” However, when he got home, he decided, “If anyone’s going to make sense of it, I’m going to.” So he told the Skirball: “I know what I want to do … I want to bring my home into the place … because every room represents a theme in my work.”

Last October, as Baseman was preparing for the show, going though all his archives and material, his mother died. She was in her early 90s. And Baseman said he misses her greatly, especially her cooking — particularly the homemade gefilte fish she served on holidays.

“Both my mom and dad were able to die in their home, at peace, with their family around,” he said. “With all they went through, and to show their kids that there’s nothing to be afraid from death. … Except, well, that I’m next, which did kind of freak me out.”

Baseman recognizes the irony that “I’m creating a show called ‘The Door Is Always Open’ and this is the first time that my parents’ actual door is not going to be open, because it’s gone.” As for the rest of us, however, we will all be able to visit Baseman’s home at the Skirball and see that, although he may still feel himself to be a work in progress, Baseman is finally at home in the world.

“Gary Baseman: The Door Is Always Open” continues at the Skirball Cultural Center through Aug. 18. For more information, visit www.skirball.org/exhibitions/gary-baseman.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.