Amir Levy/Getty Images

Amir Levy/Getty Images There is of course no comparison: Benjamin Netanyahu is not Vladimir Putin. Israel is not Russia. The purpose of this article is not to imply that anyone in Israel is doing something remotely similar to what Russia is doing in Ukraine. Its purpose is to examine the dynamics of decision-making, against an available example. It’s interesting to compare what happened to Putin when he decided to go to war, and what happens to Netanyahu following his decision to go to war over the structure of the legal system. Why interesting? Because there are things in which the similarity is evident.

Without going into the question of whether the proposed legal reform is necessary or not, when a decision was made to promote it, it was based on at least the following three assumptions: 1. There is a need for it (this is the coalition’s assumption). 2. The government has enough power to implement it (a coalition majority). 3. The cost will be lower than the benefit to the country and the coalition (because there is no point in a move that has little benefit and high cost).

These are the three assumptions that can also be attributed to Putin when he launched a war in Ukraine. He thought the war was necessary, even if we strongly disagree with it. He thought he had the power to win. He thought that the benefit would exceed the cost involved, and Putin knew that war would have some cost. Hence the similarity: Putin was wrong in at least two of his three assumptions. The Netanyahu government also seems, at least now, to have made a similar mistake.

Of course, it is not yet possible to make a definitive judgment. Can Russia conquer Ukraine? Only time will tell. The war is not over yet. But it already seems clear that Russia cannot do it as efficiently and quickly as Putin expected. It is hard to assume that Putin chose to go to war knowing in advance that he would be dragged into its second year of battle, when he is isolated, bruised and seemingly much weaker than he was a year ago.

Which of course also undermines Putin’s other working assumption: that the benefit is greater than the cost. At least now, there is no benefit at all, and the costs are real: Economic isolation, international hostility, fleeing citizens, erosion of deterrence. Russia is a wounded country. Putin is a leader in trouble. The world is openly talking about the end of his era, and even if talk is cheap and the reality is that Putin still rules Russia, such talk has meaning.

Is it already clear that the cost is greater than the benefit? Since the war is not yet over, it is difficult to say such a thing with complete confidence. We have to see what Russia will get in exchange for getting off the tree. But the possibility of high cost, little reward, is definitely there. So, even from Putin’s point of view (he believes that the war is just) at least two out of three assumptions may turn out to be wrong.

A recalculation may lead some of the ministers and Members of Knesset to the realization that even if the move is necessary, it is too risky, or too costly.

Now let’s turn to Israel (with a reminder, just in case, that there is no similarity). It is hard not to notice what is similar: a new government thought there was a good reason to make a dramatic move. The new government thought it had the power to go through with it. The new government thought that the benefit would exceed the cost. Was the government wrong? It is too early to say. But we can already say that it may have been wrong. It is possible that it embarked on this move under the assumption that it could go through with it – when in fact it can’t. Yes, the coalition has the necessary votes in the Knesset, but it was not prepared for the fierce persistence of the opposition to its move. It did not anticipate the determination of the opposition. Therefore, it could not make an accurate calculation of cost and benefit. A recalculation may lead some of the ministers and Members of Knesset to the realization that even if the move is necessary (their view), it is too risky, or too costly.

Of course, there is no certainty that such a conclusion would materialize. Psychological dynamics create a paradox that Prof. Gadi Heimann of Hebrew University describes beautifully in his book “Fear, Regret and Wishful Thinking.” It is the tendency of leaders to take risky gambles so as not to lose. That is, when they encounter a challenge that they did not expect, and which may lead them to a loss, they do the opposite of what’s logical. Instead of giving up, they double down. Heimann cites as an example the decision of Germany to launch submarine warfare during the First World War. For all the risk involved, he writes, this was “the only alternative that gave Germany any chance of victory.” In retrospect, it is obvious that this was not a wise decision, but in real time the leaders managed to convince themselves that the chance of success worth the risk.

Luckily, this does not happen with every crucial decision. But it often does. And if it happens in Israel this means that amid warnings of economic harm, fear of social rupture, boiling blood of supporters and opponents, the possibility of harmful countermeasures – the government is still going to insist on implementing its plan.

Netanyahu’s record proves that he is not a risk taker. Which brings me back to Heimann’s book. There were cautious German generals in WWI, but, as Heimann writes, “the high probability of suffering a loss turned the Germans from risk-averse to risk-loving.” For Israel today – that’s the worrying scenario.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

New poll numbers made me write the following analysis:

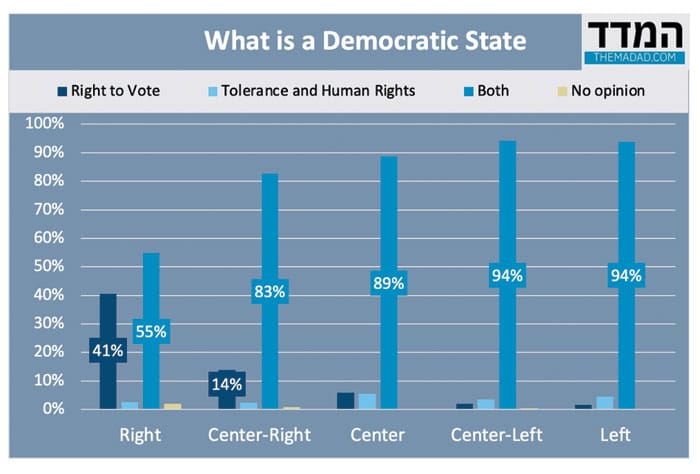

Why shout “democracy, democracy”? Not because someone in Israel wants to abolish democracy and for Israel to be an undemocratic state, but because there is a debate on the question of what democracy is … even on the right, a majority of respondents say they want a democratic country, in which there is a right to vote as well as tolerance and human rights. On the other hand, the right is the only group in Israel that has a fairly large subgroup, between one-third and one-half, who say that in their view a democratic country is “a country that has free elections and the right to vote” — and that’s it.

A week’s numbers

And here are the above-mentioned findings.

A reader’s response:

Elaine Herold asks: “Do they still talk in Israel about the issue of Women of the Wall?” Answer: not really, we currently have bigger fish to fry.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.