studiocasper/Getty Images

studiocasper/Getty Images If you are used to thinking about Israel as a country divided between left and right, or between religious and non-religious, or between Jews and Arabs, or between pro-Bibi and anti-Bibi – think again. The more significant division of Israel is somewhat different.

The two main camps in Israel today are the everything-will-be-okay camp and the we-are-headed-for-a-cliff camp. Party leaders, heads of non-profit organizations, researchers and activists are all currently engaged in an alert, lively debate concerning these two possibilities. Of course, there are parallels between these two camps and other possible divisions of the country. Most right-wing voters are in the will-be-ok camp, at least for now, at least until things turns out otherwise.

When we asked ultra-Orthodox voters (as part of a survey) what is going to happen to Israel’s economy when a third of Israel’s citizens are ultra-Orthodox (in a few decades), the answer we got more than others was “It will be fine.” Secular respondents were alarmed by this demographic projection and answered the same question accordingly. They think it won’t be okay. Some of them even told us that if such a scenario materializes, they’d rather not be here (of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean they would actually move).

The main debate takes place within the camp that is the less satisfied with the outcome of the election. It is a majority of Israelis, some of whom did not bother to vote, or voted irresponsibly for parties who did not cross the electoral threshold. It is a debate between those who say that nothing has happened yet, nor is it certain that anything truly dramatic is going to happen (as I write this column, Netanyahu is still facing many hurdles as he strives to form his coalition). The members of the planned new coalition talk a lot about their ambitious plans, but for the time being the coalition has not yet been established, and the plans are merely plans. Some of them might be realized, many others won’t.

So the will-be-ok camp isn’t quite happy with the outcome of the election and is not devoid of worries, but by and large, it is optimistic. Israel had managed to overcome obstacles more dramatic than the appointment of Itamar Ben-Gvir as Homeland Security minister, or the alteration of this or that law.

This is one camp. Call it the camp of patience, call it the camp of reserving judgment, call it the camp of wait-and-see. Opposing them, a much more vocal camp is showing signs of panic. In this camp, there is a serious and deep discussion on what to do next, and whether there is still any point in fighting for the old objectives: mutual responsibility, civil institutions, shared public sphere, common vision. Many voices within the we-are-headed-for-a-cliff camp believe that the time has come for a sectoral battle. Each group for itself, each community for itself. In the we-are-headed-for-a-cliff camp there is a lot of loud rhetoric. Raving politicians are rushing to the microphone to give us their version of how bad things will be. Some of them must compensate for their role in bringing about a bitter loss in the election. Others are positioning themselves for the next round, whenever it comes. Still others are truly worried. And they have reasons to be worried. These are reasonable people, responsible Israelis, who are seriously looking for new models for regulating the relations between groups in a country that seems to be in some kind of crisis.

Public opinion polls teach them that the Israeli debate is not just about ideology, it is about facts. Members of the Haredi community explain, without irony, that the students who graduate from their educational system are in good shape and can be useful in a modern economy. But research by the Bank of Israel shows that the ultra-Orthodox education system put its students at great disadvantage and does not prepare them for life in a modern country. This is a dispute about the actual reality, from which there is no way out. Each camp has their own set of facts — and each camp argues that the facts of the other side are wrong, biased, unfounded, non-serious.

From the facts, there’s a natural move to policy: if Haredi students are just fine, there’s no need to worry about the future of the work force, and about the growing Haredi population. If Haredi students are not fine, then the future of Israel’s economy is clouded by a demographic reality that can’t be ignored.

This is one camp. Call it the camp of patience, call it the camp of reserving judgment, call it the camp of wait-and-see. Opposing them, a much more vocal camp is showing signs of panic.

It’ll be fine – one camp says. When the time comes, they will do their part. In fact, there’s hardly even a problem, this is just hyperbole of election losers. It’ll be a disaster, the other camp says. Being optimistic is not a plan. Promising that it’d be ok is not a remedy. Israel must act and must act now. Two mindsets, two camps. They look at each other and think: these guys in the other camp are not just wrong, they’ve lost their minds.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Again, a government is formed with many small ministries whose main reason to exist is political. Here’s what I wrote about this phenomenon:

Not that there is no cause for alarm: the Israeli government that is being formed acts in a way that can only be described as “promiscuous.” But the truth is that ministries have been used in similar fashion for many years. The “Ministry of Regional Cooperation” was established by Ehud Barak to sideline Shimon Peres in the late ’90s. The “Ministry of National Infrastructures” was formed by Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996 to solve a problem he had with Ariel Sharon. And all this happened before the era of unnecessary offices such as the Ministry of Intelligence, the Ministry of Strategic Affairs, the Ministry of Higher Education, and other politically motivated inventions.

A week’s numbers

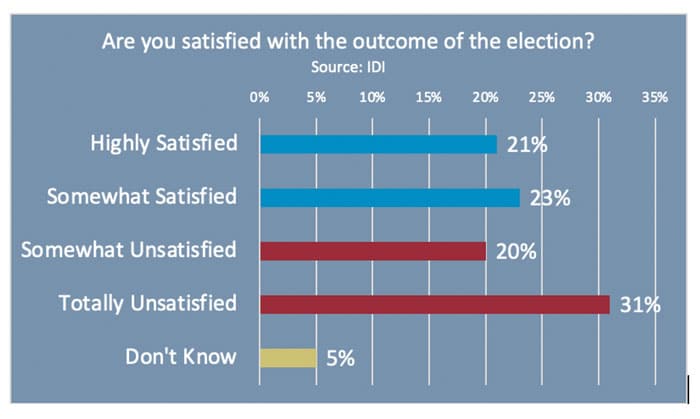

You’d expect a majority to be satisfied with the outcome of a recent election, and yet, here it is:

A reader’s response:

Yuri Nussbaum asks: “Why does it take so long to form a new government?” Short answer: the newcomers have great appetite, and they try to bite more than they can chew.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.