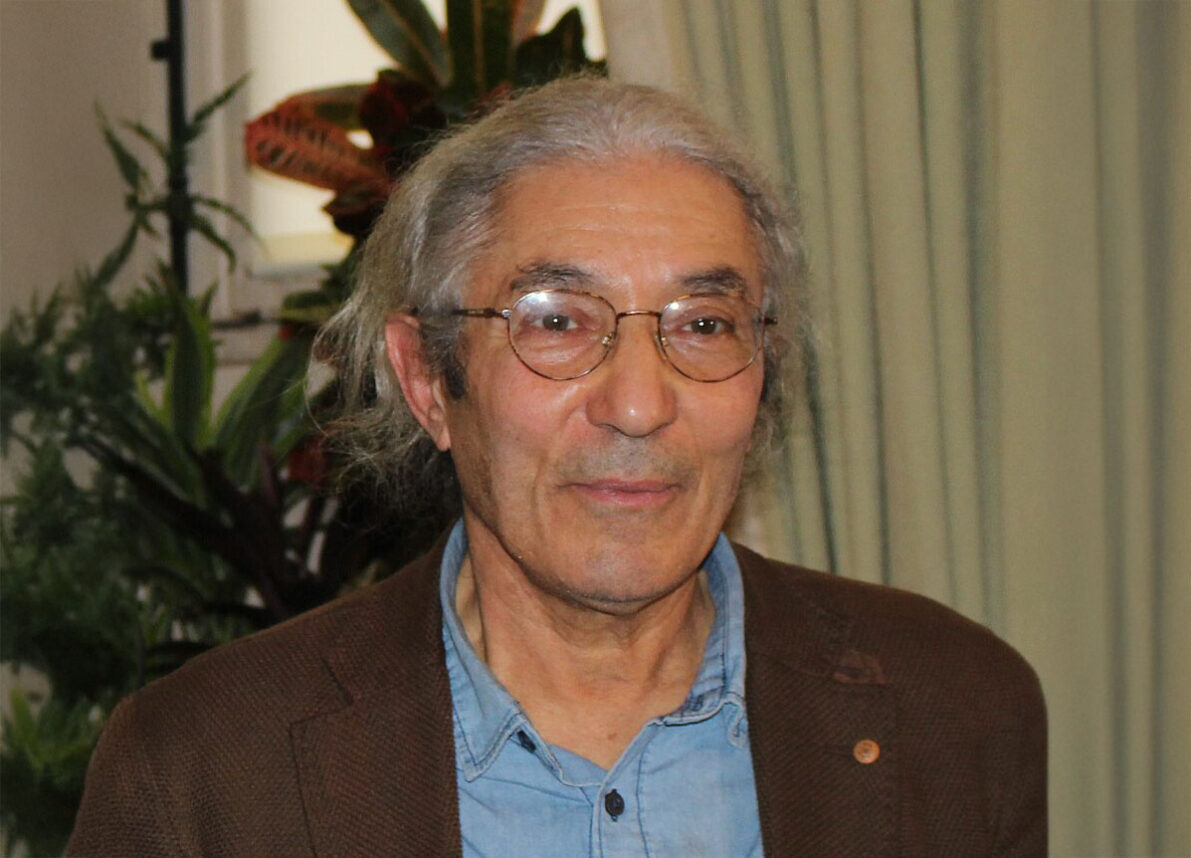

Two decades ago, after hearing the then-Col. Ehud Barak deliver a eulogy for a fallen comrade, popular Israeli poet Haim Guri predicted: “One day, this man will be prime minister.” On May 17, Israel’s voters proved him right. Barak was elected by a landslide, his 56 percent to 44 percent for the right-wing incumbent, Binyamin Netanyahu — the younger brother of the man Barak eulogized in 1976, Yonatan Netanyahu, who was killed rescuing a planeload of hijacked passengers at Entebbe airport.

Barak’s countrymen have been prophesying great things for him since he launched his military career nearly 40 years ago. When he passed out of his first officers’ course with distinction, Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin said: “If this boy doesn’t make chief of staff, there’s something wrong with the system.” Moshe Dayan, the skeptical, eye-patched hero of the 1967 Six-Day War, added: “He’s too good to be true.”

When Barak hung up his uniform in 1995 after four years in the army’s top job, Rabin brought him into his Cabinet and tapped him as heir apparent. He served briefly as minister of the interior, then foreign minister (after Rabin’s assassination in November that year). Following Netanyahu’s defeat of Rabin’s successor, Shimon Peres, in 1996, Barak was elected leader of the Labor Party.

In this spring’s election, he fought like a general. His campaign was focused. He selected his targets — the Russian immigrant voters, as well as the disenchanted blue-collar Sephardim, who had voted Netanyahu in 1996, then found themselves on the dole — and stuck to them.

“He was at the heart of every decision,” testified one of his American spin doctors, Robert Shrum. “Once he makes up his mind,” said an old friend, Ron Ben-Yishai, “he goes at it like a missile.”

Like Rabin and Dayan, the 57-year-old Barak will always be seen as a soldier turned politician. But he brings a broader, more trained intellect to the premiership. After the 1967 war, he earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and physics at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University and a master’s in systems analysis at Stanford. He is an accomplished classical pianist. Acquaintances say that he can talk as knowledgeably about the novels of Dostoyevsky and Proust as about those of the modern Israeli masters Amos Oz and A.B. Yeshoshua. He jogs, likes a good cigar and an occasional drink. The eulogy he delivered for Yonatan Netanyahu is taught in Israeli high schools for the richness of its Hebrew language. His wife, Navah, teaches English. They have three grown-up daughters.

Barak was born of pioneering, kibbutz stock in Mishmar Hasharon, where his parents still live. In the army, he commanded the top special operations unit. As Israel’s most decorate soldier — a record his television campaign spots highlighted remorselessly — he won the Distinguished Service Medal and four citations.

In May 1972, he led a squad, disguised as white-overalled maintenance men, that stormed a hijacked Belgian airliner at Tel Aviv Airport. A month later, he and his commandos snatched five Syrian intelligence officers, on a tour of inspection in southern Lebanon, as a bargaining counter for Israeli prisoners of war. The following spring, dressed as a buxom woman tourist with a brunet wig, Barak led a hit team that landed in Lebanon from the sea and killed three Palestinian leaders in their Beirut apartments.

After graduating from special forces, he went on to command an armored division and the intelligence corps. Subordinates dubbed him “Napoleon,” a reference not just to his stocky build but to his supreme self-confidence and intolerance of those who failed to measure up to his standards.

Amos Gilboa, Barak’s deputy at military intelligence, said: “He is very demanding. Freedom to do things without his permission is a privilege for those he trusts. You have to get it right. If he sees that people handle things loosely or against his directives, he will come down on them without mercy.”

Ron Ben-Yishai, a military commentator who served with Barak as a young officer and studied with him at university, added: “He’s very determined, very ambitious. He’s a man of his word. He thinks very fast and tends to rely on himself. But he reacts slowly. He’s a calculator, a tough guy. It is very difficult to pressure him.”

As a civilian politician, he has learned to seek advice. “He listens,” said Ben-Yishai. “He respects different opinions. He’s open-minded. He grasps things very quickly. The downside is that he gets bored very easily, then he neglects things he ought not to neglect.”

On the campaign trail, he learned to glad-hand the voters, if not quite to kiss their babies. “He was never an emotional person,” Ben-Yishai said, “but once he saw that it was important to hug people if he wanted to win, he became one.”

Similarly, the strictly secular Barak has started quoting Jewish texts, something his friends say he never did before. He is courting religious parties in an attempt to build a government of national reconciliation. “He quotes the Bible, and quotes it fluently, because he thinks he needs it,” said Ben-Yishai. “It’s an instrument, but he’s not a liar. He wasn’t anti-religious before. He’s always respected the Jewish tradition.”

Like Dayan and Rabin, Ehud Barak is a Labor hawk destined to make peace. He starts with a huge fund of goodwill, at home and abroad. Israeli analysts are warning him not to squander it. “The real test of his leadership,” Sima Karmon wrote in the mass-circulation Yediot Aharonot in the heady dawn of May 18, “starts this morning.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.