Most of us remember our parents telling us when we were

children that when they were our age they had to walk two miles, every

day, in the snow, uphill, both ways, to go to school. In

ancient times we can imagine our ancestors telling their children that when

they were their age they were slaves to Pharaoh. Our rabbis liked that line so

much that they forever imprinted it on our minds by including it in the

haggadah: “In each and every generation a person should see himself as if he

personally went forth from Egypt.” It is not sufficient for us to read or tell

the story — we are to feel as if we were experiencing the liberation from

slavery into freedom.

Those among our people who survived the Holocaust do not

need to be reminded of their liberation. Each and every day the Holocaust

survivor remembers the hunger, the humiliation and the degradation of his or

her experience. Recurring nightmares and certain experiences can trigger and

bring back in an instant the memories and horrors of the past. These people

appreciate more fully each and every blessing of food, health, warmth and

comfort.

The difficulty is in transmitting that appreciation to the

next generation — and so we recite each year: “In each and every generation a

person should see himself as if he personally went forth from Egypt.”

Similarly, the most oft-repeated verse in the Torah, no fewer than 36 times,

tells us, “To treat the stranger with kindness, because you remember how your

were treated when you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” Sociologists would

tell us that those who were abused as children will likely grow up to be

abusers. The Torah, however, does not cut us any slack. It is precisely because

we remember our persecution and oppression that Jewish people are to assist the

widow, the orphan, the stranger, the poor and all the other vulnerable members

of society. Not only may we not abuse others, we are obligated to be most

helpful to those who are most likely to be mistreated by others.

Rather than using our ignoble historical past as an excuse

to receive sympathy we are held to a higher standard because of the oppression

we remember at the hands of Pharaoh and the taskmasters. Despite the fact that

most of us were born in America, this wonderful land of abundance, we are

bidden to annually remind ourselves of the gnut (our scornful past) and humble

beginnings as a people. Though we are physically in Los Angeles and in

comfortable homes, we identify as a member of an ancient people subjected to

countless persecutions. We have survived to relive the story and thereby make

sure it never happens again — to us or to anybody else. Our awareness of our

own material blessings is tempered by our acknowledgement that the world is

still unredeemed. We are not permitted to be too comfortable. The eastern

corner of our home is to be unfinished, reminiscent of the destruction of the

ancient temple. Our blessing after the meal during the weekdays begins with

Psalm 137: “By the rivers of Babylon there we sat and wept for Zion,” reminding

us of our exile from Jerusalem 2,500 years ago. At a wedding when we celebrate

a supremely joyful moment, we break a glass. Our material blessings are tithed

to tzedakah — to hasten the final redemption for all.

What a strange challenge. We are to live in two worlds. We

work hard to provide for our families all the blessings of this rich culture —

but we are to be reminded: “This is the bread of affliction our ancestors ate

in the land of bondage. This year we are slaves … next year may we be free;

this year we are here, next year may we be in the land of Israel.”

Twice each year (the last moment of Yom Kippur and at the

end of our Pesach seder) we recite the words: “Next year in Jerusalem.”

Even those in Jerusalem recite these words. We are never

quite in the Jerusalem that was intended by those words. Those words imply the

time of redemption for all mankind.

I spoke to my son today. He lives in Jerusalem. He tells me

of a bus that was bombed, the eight who were killed and the 60 who were

injured. This world is the earthly Jerusalem. He then went to the Wall to pray,

with those who long for the Yerushalayim Habanuyah — the rebuilt and redeemed

Jerusalem, the true City of Peace to which we all intend our prayers.

We are not permitted to lose hope or lose our sense of

balance. We do not dwell excessively on the bitter herbs or bitterness of life.

We combine the bitter herbs with the charoset — the bitter with the sweet.

Israel’s national anthem is “HaTikvah” (The Hope).

Our momentary abundance does not blind us to our collective

poverty. And our sadness at the realization of the hunger, illness and pain in

this world does not blind us to our mission. “Next year in Jerusalem” is a

prayer and a directive. We are to guide our actions and inspire our hearts and

minds to work toward a rebuilt Jerusalem. Our prayers are directed to our

inmost heart to move our hands to bring about the final redemption.

This year we work to bring about the Jerusalem that we will

enter next year.

May Elijah drink from his cup at our seder this year and

foretell the coming of that great and awesome time, the time of peace for all

humanity. Â

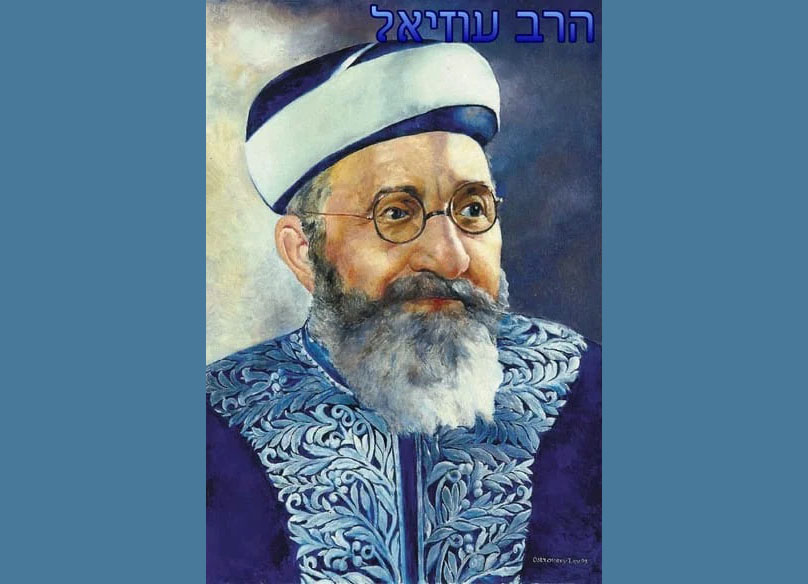

Gershon Johnson is rabbi at Temple Beth Haverim in Agoura Hills.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.