Technically, Claudio Estrada Jr. became a Jew on March 9, 2015, but “spiritually inside,” he said, “I was a Jew a long time ago.”

Between rounds of Jewish geography, Estrada shared his journey into Jewish life with the Jewish Journal in a Google hangout interview from his office at the PUC Community Charter Middle School in Lake View Terrace, Calif., where — at the relatively young age of 30 — he is the principal for sixth through eighth grades.

In the background behind him, a massive wall calendar charted the year ahead for the school. The walls were marked with the school’s approved colors — red, blue, orange and white — and bore framed dictionary pages with larger messages written on them, one reading “You got this” and another “Let there be light.” A poster featuring an Oscar statue read, “We all dream in gold.” A program from “The Lion King” was a prominent cultural artifact — Estrada has seen the theatrical production nine times in three languages. A signed Seattle Seahawks jersey — Derrick Coleman, No. 40 — is also framed; and inspirational books and digital photo frames mark some personal touches. And most of this is not even for Estrada, who is trying to make his office “as inviting as possible.”

“The principal’s office used to mean, ‘You’re in trouble,’ but we just have a lot of conversations here. We are doing something different here,” he said, referring to the social emotional education approach that his school uses in the classroom.

“We haven’t had any fights,” he said, noting that the most common violation is cyber-bullying or being verbally disrespectful. “We do a good job laying down the law; back-to-school assemblies let them know what not to do this coming year.”

He said, noting how little time he spends in that office, “I’m like Moses, I like being with the people. … He is the one who has the vision, sees the bigger picture, can get everyone together and move forward.”

It’s not the first or last time in the conversation that he expresses a kinship with one of the most famous Jewish leaders of all time, and as he revealed the steps on his journey, it’s easy to see why: This self-described “first-generation Jewish Mexican-American” has been blazing his own path — and inspiring others to lead — since way before his conversion was finalized.

Estrada’s family immigrated to the United States from Mexico in the 1950s; he describes his home as “somewhat Catholic,” but at school he was surrounded by Jewish families, and absorbed Jewish holiday customs and culture. At college, he found himself “needing something higher than myself to feel proud of,” and began exploring Judaism.

College itself was a diversion from the family path; he was the only one of four siblings who had a chance to go to UCSD and study abroad. His family’s reaction —“Why are you going away? Why aren’t you staying here? Isn’t it/aren’t we good enough? Why break the mold?” — provided a flavor of the response that news of his conversion would provoke.

After college, Estrada joined Teach for America; in 2012, he connected with the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation’s (CLSFF) REALITY program, an Israel trip for fledgling educators, whom he described as “brothers and sisters wrestling in the same work.”

“It was the perfect backdrop for a unique experience of self-discovery through the lens of tikkun olam.”

Philanthropist and CLSFF founder Lynn Schusterman connected him to ROI leaders in Mexico; about a year later, he joined a group of young professional Latin American Jews — “Jews that I thought never existed,” he said — in Mexico City, to talk about their Jewish communities’ social issues and to build homes for two local families in a remote part of the city.

Next on Estrada’s Jewish journey was a program run by Rabbi Shira Stutman from the Sixth & I Synagogue in Washington, D.C. After that, he found the American Jewish University’s Miller Intro to Judaism Program.

“Since my first class, it was magic,” he said of meeting Rabbi Adam Greenwald, the director of the Miller Program. “I immediately connected with him. He’s also young and is able to relate, and make narratives more captivating. His style and pearls of wisdom are so profound and rich in Jewish values; he is a gem.”

While many individuals studying for conversion do so with a Jewish partner or friend, Estrada says his own five-year process of exploration and ultimately, conversion, was “my own choice and decision, and it’s been a blessing ever since.”

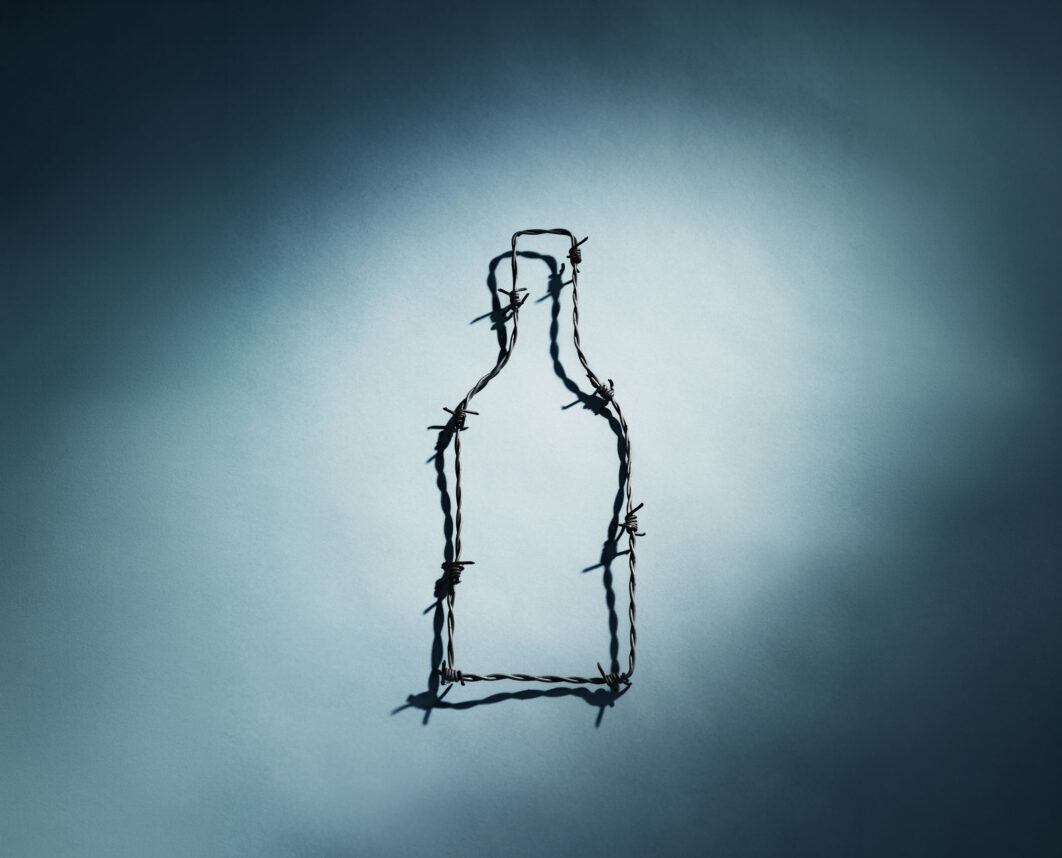

He was particularly drawn to Judaism’s belief in one God, and, as an educator, felt connected to Holocaust works such as “The Diary of Anne Frank” and Elie Wiesel’s “Night.”

“Judaism is very poetic and, depending on the day, any portion of the Torah can have a different meaning depending where you are in your life. In Catholicism, there’s this arbitrary idea of planning for something after life. But what I admire about being Jewish is that we’re focused on being active in the present, sharing positive energy, leaving our world much better than where we found it.”

One family, the Alperts — whom he met when he was 18 and working as a part-time schoolyard assistant — has become what he still calls his “Jewish family.”

His own family reacted to news of his Jewish identity with some denial, but for Estrada, his mother’s opinion mattered most. Finally, she said, “If that’s what makes you happy, then do it, enjoy it and make it your own,” Estrada recalled. “That was a huge step forward.”

His mother has since studied with her son and attended seders with him. Estrada got her a mezuzah, and next to her Christmas tree she has a menorah. His siblings have also accepted Estrada’s faith with curiosity.

When he lost his father — “a traumatic life experience,” he said — in July 2010, Estrada felt supported by the Jewish community and found the Jewish prayers to be deep and profound. His family did Catholic Mass in his father’s memory; Estrada lit a yahrzeit candle. (The conversation with the Journal happened the day after his father’s sixth yahrzeit.)

Estrada now brings his Jewish passions to work with him. Since 2014, Greenwald has come to Estrada’s school to offer students a chance to ask questions about Chanukah; he also brought a Holocaust survivor to Estrada’s school for a conversation with students.

While Shabbat observance and kashrut continue to challenge him, he feels there’s “something cosmic” about prayer. Since he doesn’t understand much of the Hebrew, he connects through the music, and is grateful for the annual opportunity to engage in personal reflection in advance of the High Holy Days.

“I enjoy the series of traditions that allows me to better explore myself, align my moral compass with God, ask for forgiveness and forgive others, and start fresh with a new lens and outlook to life,” he said.

This year, he’ll be celebrating in Vietnam, at the wedding of his Jewish best friend from college. He already knows they’re having a Shabbat program for out-of-towners, and his friend’s mother will help him connect to local High Holy Days services.

“It’s a time to be visually and spiritually connected with something bigger than yourself,” he said in contemplating the centrality of the coming holidays, “a time to publically say, ‘I’m a Jew,’ in my personal and professional life.”