My grandfather Herschel Nahum was born into an Orthodox family in Montreal in the midst of the Great Depression, and moved to Los Angeles as a teenager in the 1940s. As a storyteller, he’s nothing if not consistent. Three, maybe four classic childhood tales lie at the heart of his repertoire, as much a part of our visits to the grandparents’ house as his lectures on smooth golf swings and gefilte fish from a jar.

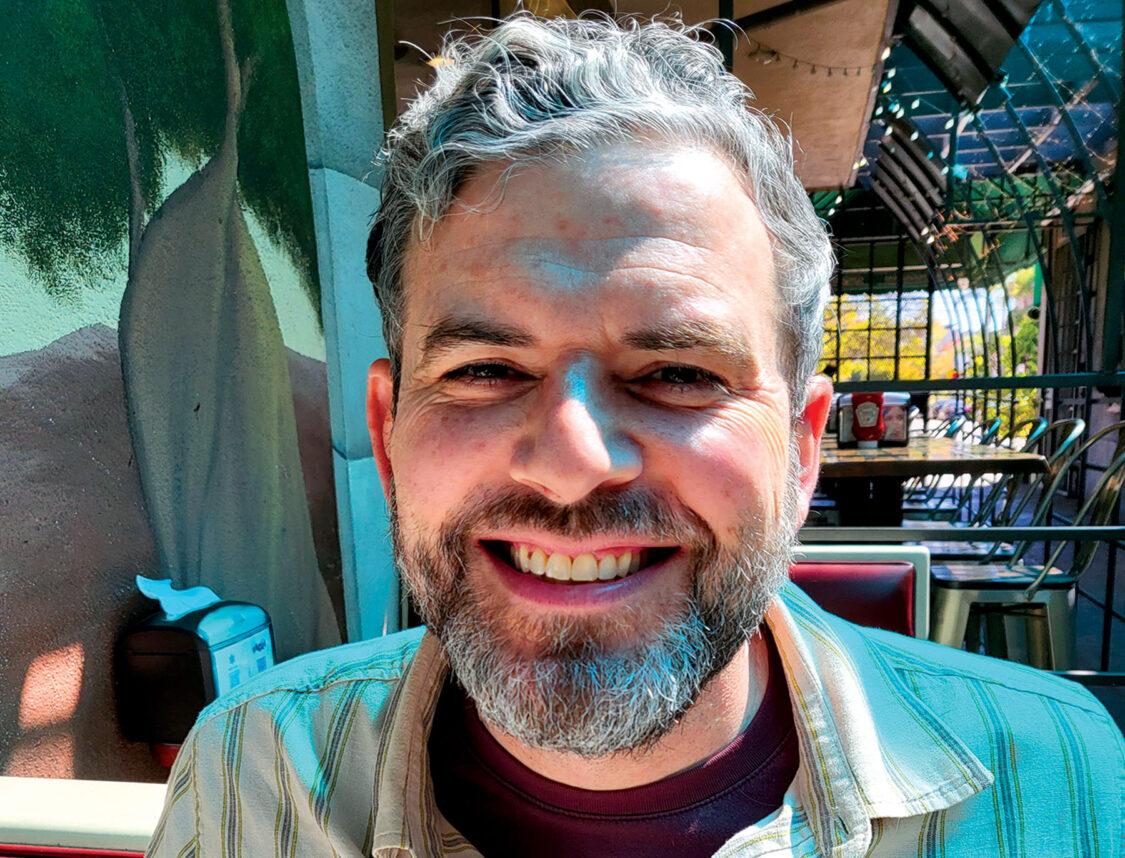

Nahum (right) and his younger brother (left)

Nahum (right) and his younger brother (left)

There was the one about Sandy Koufax: You know, Sam, I saw him pitch in ’63. The crowd was wrapped all around the ballpark before the game, waiting to see him on the mound. But he was off that night, so they pulled him after the fourth inning. And you know what? When he left the game, so did everybody else!

Or the one about the kosher butcher chasing chickens for picky babushkas: I vant dat one!

Which naturally led to the story about free food being shoveled into the nearest available purse: Your bubbe would take the bus all the way downtown just for the free apples in the hotel lobby!

Or the one about … well, you get the picture. They were familiar, comfortable and beloved, and you could laugh before the punch line because you always knew exactly when they were coming. And so when he told me the following story — one so out of character as to be unwelcome were it not for the delightful ending — I was shaken from my complacency as a listener and forced to pay attention. Years later, I couldn’t be happier that I did.

He was a teenager in 1945, newly arrived in Los Angeles with his mother, stepfather and younger brother crammed into a little apartment in Hollywood. Like every 13-year-old from time immemorial, he needed money, the kind of walking-around money that transforms a slouch-shouldered youngster into a man about town. This led young Herschel into a street-front newspaper stand on Franklin Avenue where, like so many other Jewish boys of the era, he hustled selling papers and magazines, 5-cent cigars and packs of cigarettes, and all the other pocket-fillers of the 1940s working man. His boss, Bennie, like plenty of other Jewish men of the day, ran a book out of the shop, taking bets on any and every sporting event under the sun but really specializing in setting up some good off-track action on the ponies churning dust and mud at Santa Anita Park in Arcadia.

Bennie had a set system. He’d take his action over the course of the day and then, a little before the gates were scheduled to open, he’d slip off to the adjoining barbershop (where some of his most loyal patrons could be found poring over newspapers in English, French, Hebrew and Yiddish, puffing away on their omnipresent cigars) and settle into a pay phone booth to call in the bets to his partner at the track. Once he’d closed his book, figuratively and literally, on the afternoon’s work, he’d head home for supper and leave young Herschel to mind the register until sundown.

No one argued that Bennie was a good bookie, and his regulars were content enough to keep coming back, telling their friends all about his nice little operation until it attracted the wrong kind of attention from the blue-clad beat-walkers he’d been hoping to avoid. Sure, Bennie had been arrested before, but a quick greasing of the right palms in the otherwise irreproachable Los Angeles Police Department had always gotten him back on the street in a flash.

This time was different. This time, the cops were coming for Bennie in plainclothes, without any warning from his friends downtown who liked to play the ponies from time to time (sure, who doesn’t?), and who were keen on sticking it to that smart-ass bookie on Franklin Avenue.

They came in, flashing badges and looking all business, and Bennie turned white as a sheet. But being a man of opportunity, if not of great integrity, he slipped out the back just as they stepped into the front of the shop. This left Herschel, a generous 5 feet 4 on a good day, standing smack in the center of the crime scene with two burly detectives towering over him, with his heart thumping madly in his chest. All right, don’t waste our time. Show us the book and we’ll get out of here, otherwise we’re tearing everything apart.

And Bennie’s young employee, struck dumb with fear at his first brush with the law, watched as they did just that. Those two cops went through every cigar box and magazine in the joint, scattering wrappers and grunting through their cigarettes as the whole neighborhood walked by, too nervous to stop but too curious to pass up such a tempting shot at street-corner voyeurism.

After what seemed like an eternity, they found it: a ledger of bets and balances and payouts as obvious as an accountant’s binder, tucked slyly under the cash register drawer, as deliciously indicting as a piece of evidence could be.

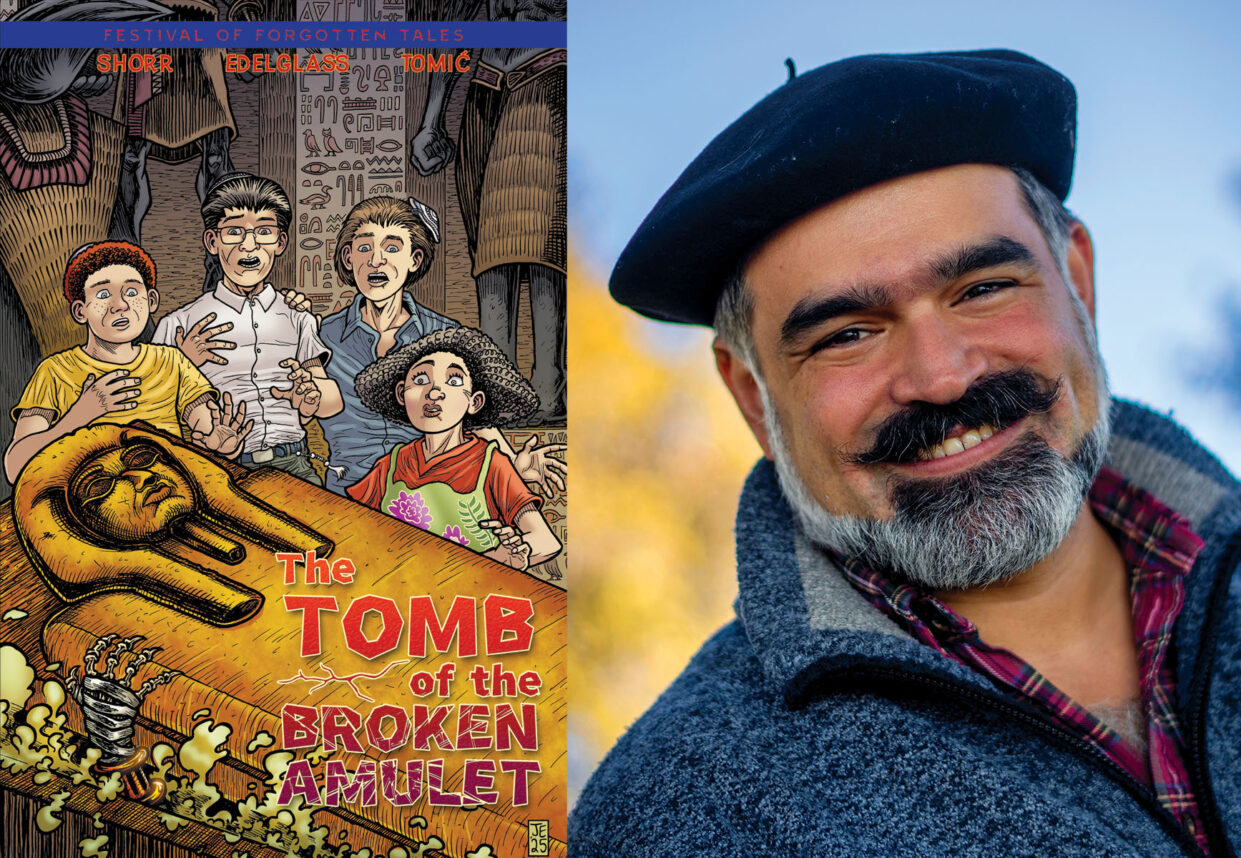

Herschel Nahum

Herschel Nahum

Except, of course, it wasn’t in English.

C’mere kid, we know this is it. Right? Read this to us: the horses’ names and bettors’ names and race times. It’s all here, ain’t it? And Herschel Nahum, pride of Congregation Shomrim Laboker, looked up at the detectives with the widest, most innocent pair of eyes in Hollywood and solemnly declared: Detectives, I don’t read Hebrew.

Sam Jefferies is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C., an occasional visitor to L.A., and a sports and pastrami enthusiast.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.