In the fourth game of the series to determine the 1944 baseball championship, a Jewish rookie left fielder hit a home run that helped seal a 7-1 victory. The hitter was Thelma (Tiby) Eisen, the team was the Milwaukee Chicks, and the play-offs were to determine the champion of the All American Girls Professional Baseball League. Eisen went seven for 28 during the series (a .250 batting average) and stole eight bases. The Chicks eventually won four out of seven games against the Kenosha Comets to secure the title on September 18, which happened to be the first day of Rosh Hashana.

Women have played baseball since the sport was invented in the mid-1800s—in all-women leagues and on teams with men, in amateur and professional leagues, with softballs and hardballs. Soon after the first women’s colleges were established in the 1860s, some of them—including Vassar, Smith, Wellesley and Mount Holyoke—fielded baseball teams. In the early 1900s, Jewish settlement houses, like the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA), encouraged girls to play baseball and sponsored teams. High schools, local businesses and even synagogues sponsored girls’ softball teams, which proliferated in the 1930s and 1940s.

An important milestone for women in baseball came in 1943, when Philip Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs, founded the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL). He figured that baseball fans might buy tickets to see women play the game while many of their favorite major league stars were in the military during World War II. The league lasted until 1954. Although the rules frequently changed, for most of the AAGPBL’s existence, they played hardball and pitched overhand. In its twelve years, over 600 players filled the league’s rosters. It was almost forgotten until 1992, when Penny Marshall’s film “A League of Their Own” became a smash hit.

Four AAGPBL players were Jews.

Eisen (1922–2014) was by far the best player of the four. She was born in Los Angeles, one of four children of David Eisen, an Austrian immigrant, and Dorothy (Shechter) Eisen, from New York City. She was already participating in semipro softball by age 14, playing for a team called the Katzenjammer Kids after its manager George Katzmann.

After graduating from Belmont High School in 1941, Eisen attended Santa Monica College part-time. An outstanding all-around athlete, at 18 she play fullback in a short-lived professional football league for women in California. When the Los Angeles City Council banned tackle football for women, her team moved to Guadalajara in Mexico. After attending a tryout in Peru, Indiana, she was assigned to the Chicks (which soon moved from Milwaukee to Grand Rapids) and later played outfield for the Fort Wayne (Indiana) Daisies and Peoria (Illinois) Redwings.

During her AABPBL career (1944–52), she had 3,706 at-bats, a .224 batting average and 674 stolen bases, second-best in League history. Her 591 runs scored ranks third all-time. In 1946 she led the league in triples, stole 128 bases, and was selected for the All-Star team. In the winter of 1949, she toured Central America, Venezuela, and Puerto Rico with the AAGPBL. In her last year in the league, she was a member of the pennant-winning Fort Wayne Daisies.

Eisen enjoyed the notoriety of being a pro athlete. “When we walked down the street people would ask for our autographs, ask us where we were from. They wanted know all about us,” she said. “It was big time in these small towns.”

However, initially Eisen’s family didn’t believe that “nice Jewish girls” should play baseball. But after she played in a charity game for a Jewish hospital, “my name and picture were in every Jewish paper,” she recalled, and her family was bursting with pride.

“You bet that I am proud of [being Jewish],” Eisen told Larry Ruttman for his 2009 book “American Jews and America’s Game,” “because I think that Jewish people have done so much for the world. They’ve been through enough.”

But, she acknowledged, “When I played ball I didn’t feel any special responsibility as a Jew to excel. Nobody ever asked me what my religion was, and I would go to church with girls of different religions.” She told Ruttman that she didn’t confront antisemitism while playing in the AAGPBL.

However, initially Eisen’s family didn’t believe that “nice Jewish girls” should play baseball.

After the AAGPBL disbanded, Eisen worked as an instrument calibrator for a firm that made medical devices and then worked for the telephone company. She also played softball for the Orange Lionettes, who won the Amateur Softball Association championship, and field hockey for the Shamrocks of the California Field Hockey League. She was also an outstanding golfer. Into her 80s, she gave youth baseball clinics through several nonprofit organizations in the Los Angeles area. In 1993, she helped establish the women’s exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, and in 2004 she was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.

Anita Foss (1921–2015) started playing baseball at a young age with her four brothers. She was captain of her (Providence, Rhode Island) high school softball team and a star on the Riverside Townies, the Rhode Island women’s champion softball team. After high school, she married, but her husband was killed in action in World War II.

To help heal her pain, in 1948 she attended an AAGPBL tryout in New Jersey and earned a place on the roster for the Springfield (Ill.) Sallies, which sent her to Florida for spring training. “That was the right kind of medicine to get away,” she recalled.

Foss was truly a wandering Jew. She played in only 28 AAGPBL games over two seasons (1948 and 1949), but wore the uniforms of four teams—the Springfield Sallies, Muskegon Lassies, Grand Rapids Chicks, and Rockford Peaches—pitching and playing second base. (The league frequently moved players around to guarantee a competitive balance).

Soon after leaving the league, Foss moved to Santa Monica and worked for Douglas Aircraft. The company asked her to train a man for a supervisory job. She complained that she knew how to do the job and deserved to get it. “The next thing you know, I was in charge,” she recalled, becoming the first female supervisor in her department, responsible for over 30 employees.

She played in local semipro baseball and softball leagues and was also an avid golfer and bowler. In 2005, she earned the Woman of the Year Award from Santa Monica YMCA for her contributions to the community.

Blanche Schachter (1923-2010), born in Brooklyn, started playing baseball on her synagogue team. She graduated from Hunter College with a degree in physical education and excelled in three sports: tennis, basketball and field hockey. Hunter didn’t have a softball team, but she played in various leagues in the New York City area. While working as a New York teacher, she also pitched, caught and played third base for the Greenwold Jewells of the American Softball League, one of the best teams in the country at a time when women’s softball was a popular sport.

In 1945, in a game against a women’s army corps team, Schachter, who was ambidextrous, played one inning at every position. In the ninth inning, she took the mound as a right-handed pitcher, struck out the first two batters on six straight strikes, then switched to throwing left handed and got the final batter out.

Schacter joined the AAGPBL’s Kenosha Comets in 1948 as a catcher. But she injured her knee and played only nine games in the league. She returned to New York to work as a gym teacher, but also played with the Arthur Murray Girls in the semi-professional American Girls Baseball Conference and played guard with the Queensboro Starlets in the Metropolitan Girls Basketball League. After retiring from the New York school system, she moved to western Massachusetts and worked as a high school tennis coach.

Bea Chester (1921-?) is the most mysterious of the four Jewish women in the AAGPBL. She was the daughter of Hilda Chester, perhaps the most famous fan in baseball history. Starting in the 1930s, Hilda regularly attended Brooklyn Dodgers games at Ebbets Field. Her extremely loud voice, accompanied by a cowbell, could be heard throughout the stadium. She would heckle the opposing teams’ players and managers and frequently lead fans in snake dances through the aisles. Taken by her loyalty, enthusiasm and popularity, The Dodgers gave her free tickets in grandstand seats, but she preferred to sit in the bleachers, where she’d hang a sign wherever she sat, proclaiming “Hilda is Here.”

Little is known about Hilda Chester’s private life. She was married and the couple produced a daughter, Beatrice. Soon Hilda’s husband and Bea’s father died, but there is no record of when or how he passed away.

Bea was raised at the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Articles in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in February 1932 and December 1933 mention that a student named Bea Chester played mandolin solos at events sponsored by the institution. She was a star athlete at Brooklyn’s Thomas Jefferson High School, excelling in many sports, The school’s 1939 yearbook cited her as the “Class Athlete,” describing her as “the ‘he-man’ of girls’ sports” who “bowls, plays ping pong … She possesses letters in tennis, volley ball, basketball, baseball, hockey, shuffleboard, deck tennis, badminton … she has won a trophy at Manhattan Beach for the hundred yard dash, the running broad jump, and in baseball and basketball throw.”

Bea Chester was one of the AAGPBL’s original players, but had a short-lived career. She appeared in 29 games as a back-up third baseman for the 1943 South Bend Blue Sox and the 1944 Rockford Peaches. She batted .190 and .214 in those two seasons. Her name appeared in box scores and stories about the games she played, but after she left the AAGPBL she became an invisible figure. It isn’t clear what she did or where she lived. She apparently had a son who was raised by her mother. In May 1948 New York Daily Mirror sports columnist Dan Parker reported that Hilda “is a grandma now and has decided to bring up young Stephen as a jockey instead of a Dodger shortstop.” There was no public notice of when or where she died.

Margaret (Wiggy) Wigiser is not included among the four Jews in the AAGPBL, but her life raises the age-old existential question: Who is a Jew? Born in Brooklyn in 1924, the daughter of an Orthodox Jewish father and a Catholic mother, Wigiser started playing baseball on a synagogue-sponsored team. She was an outstanding multi-sport athlete at Seward Park High School and at Hunter College. She joined the AAGPBL while she was in college, playing during three summers and returning to Hunter each fall. She played outfield for the Minnesota Millerettes and Rockford Peaches in 1944 and remained with the Peaches in 1945 and 1946. She played for a Chicago team for two years in the rival National Girls Baseball League, then returned to Hunter to earn her master’s degree. Wigiser worked for decades as a high school school teacher in New York City. The public schools annually present the Margaret Wigiser Award to the city’s outstanding female student athlete.

Margaret (Wiggy) Wigiser is not included among the four Jews in the AAGPBL, but her life raises the age-old existential question: Who is a Jew?

In 2016, a nonprofit group called Jewish Major Leaguers produced a set of baseball cards that included Wigiser, but she informed the group that she’s Catholic. The group quickly pulled her card from the remaining inventory.

Since the 1970s, the number of girls and women, including Jews, playing baseball and softball in Little League, high school, college, and burgeoning professional leagues, including some otherwise all-male teams, has increased dramatically. This is due in part to Congress passing Title IX in 1972, the inspiration from films like “Bad News Bears” (1976) and “A League of Their Own” 16 years later, and activists like Justine Siegal. In 2009, Siegal, who is Jewish, became the first female coach of a professional men’s baseball team, when she worked for the Brockton Rox in the independent Canadian American Association of Professional Baseball. In 2015, the Oakland Athletics hired her for a two-week coaching stint in their instructional league in Arizona, making her the first female coach employed by an MLB team. As founder of Baseball For All, she’s been a trailblazer in training girls from pre-teens to college age to play baseball, including a growing number on rosters of otherwise all-male college teams and on women’s college teams today.

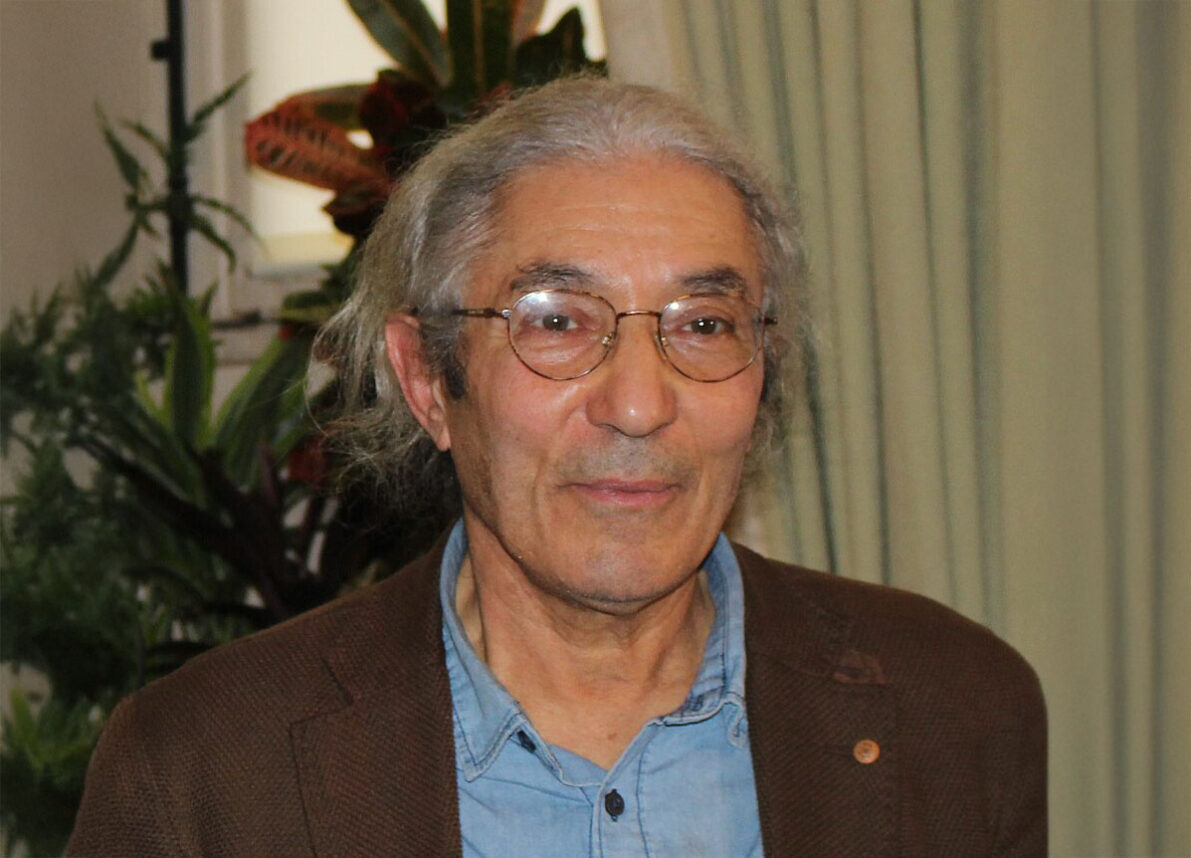

Peter Dreier is professor of politics at Occidental College. His most recent books are “Baseball Rebels: The Players, People, and Social Movements That Shook Up the Game and Changed America” and “Major League Rebels: Baseball Battles Over Workers’ Rights and American Empire.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.