As the parent of a preschooler, I am becoming well-versed in the prompt, “Please use your words.” What I’ve learned is that for a very young child who is just learning to speak, it often seems much easier to express one’s self in response to injustice (perceived or real) using a swift action — hitting, biting, pushing, etc. — versus taking the time to formulate the necessary words to get the point across. For some of us, this taste for action and reaction lingers long past our development of sophisticated language.

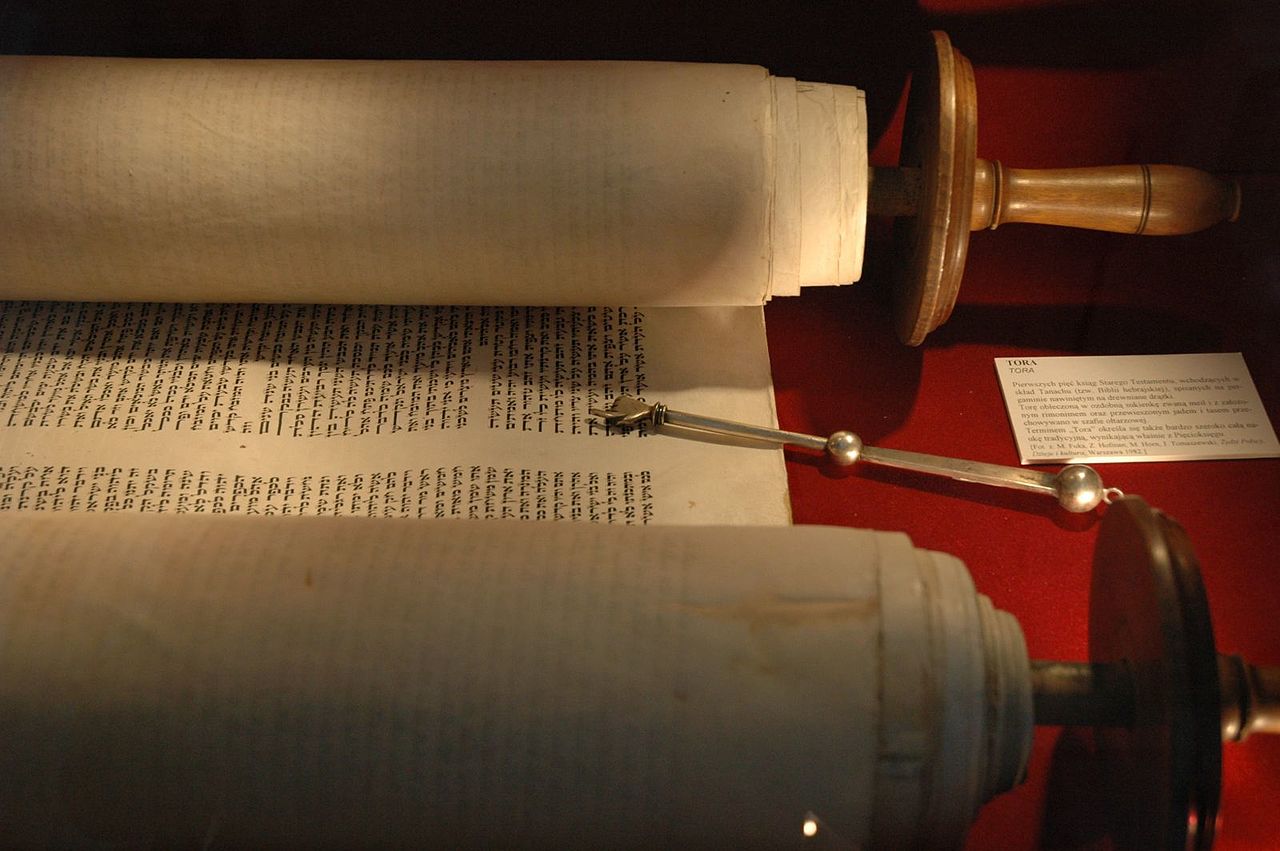

In this week’s parsha, Chukat, the Israelites are complaining of thirst. God commands Moses to assemble the Israelites and tells Moses to hold up his staff and “order the rock to yield its water” (Numbers 20:8). From this rock, God promises, water will flow and quench the thirst of the stiff-necked people.

God says, speak to the rock. And inexplicably, Moses doesn’t. Or he can’t. Or he won’t.

In any event, Moses disobeys. He smashes the rock twice with his staff.

Water comes forth. The Israelites drink.

And God tells Moses he will not enter the Promised Land because of it.

The first word to jump out at me in reading God’s initial command to Moses is the word “the” (or in Hebrew, the preposition ha preceding the word “sela”). Why does Torah say “the rock” instead of “a rock”? Have we met this rock before? Surely in the desert landscape there were many rocks. What makes this particular rock special? How did Moses know which rock was “the rock” with which he was meant to speak?

Perhaps the use of the definite article here is a foreshadowing. This is not just any rock. This rock represents Moses’ greatest struggles. This rock has followed him for years and years. Of course, Moses knew which rock to hit.

As a young man, Moses witnessed deep injustice. When he saw an Egyptian taskmaster strike an Israelite slave, he looked left and right, and mirrored the violent act, striking and killing the Egyptian taskmaster. No words, just action.

The next day, Moses witnessed a second injustice: two Hebrew slaves fighting. He approached them and asked, “Why do you strike your fellow?” The Israelite responded, “Who made you chief over us? Do you mean to kill me as you killed the Egyptian?” Moses was frightened. He realized that his secret was out and he fled. No words. Action.

Moses fled to Midian, and there, God approached him in a burning bush. God told Moses, “I will send you to Pharaoh, and you shall free My people, the Israelites, from Egypt.”

Moses replied, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh … Please, Adonai, I have never been a man of words.” Moses knew himself. He was not a person of words.

But God was insistent. God said, “Who gives man speech? Who makes him dumb or deaf, seeing or blind? Is it not I, Adonai? Now go, and I will be with you as you speak and will instruct you what to say.” God believed that he could change Moses. That he could make him a man of words.

I wonder if Moses reflected on this exchange as he stood by the beaten rock, water flowing freely from it, next to his brother, and before the people. Moses struck the rock, water flowed out, and God said, “Because you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people, therefore you shall not lead this congregation into the land that I have given them” (Numbers 20:12).

Did God get it right? Was this really about mistrust? Or a negation of sanctity? Or was this about something much more fundamental: Moses’ inability to change and God’s inability to change him.

What might Moses have said to the rock if he could/would have spoken?

In the end, God can tell Moses, “Use your words,” but the command is where it ends. The speech — the growth, the change, the evolution — they were up to Moses.

Ecclesiastes tells us, “A time for silence and a time for speaking.” But, in the end, this week’s parsha is not only about speech and silence. It is about Moses facing the rock. His rock. And rising above his own limitations. Or not. It is about realizing full potential, or missing the moment.

And so it is for us. We, too, have found ourselves, or find ourselves, or will find ourselves in the desert. Wandering. Facing the rock that follows us. For some of us, the rock is a proclivity to react or act instead of taking time to listen or speak. For others, it is impatience or apathy, defensiveness or rage.

We, too, have limitations. Limitations that repeat themselves. Like Moses, again and again, there are aspects of ourselves that hold us back, which we seek to change.

And we, too, will be called upon again and again to stand before our own rock. We will have our own opportunities to rise above our limitations. Or not. For us, the Promised Land is still so very much a possibility. We stand, too, staffs poised. The question for us is: Now what?

Rabbi Jocee Hudson is an associate rabbi at Temple Israel of Hollywood.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.