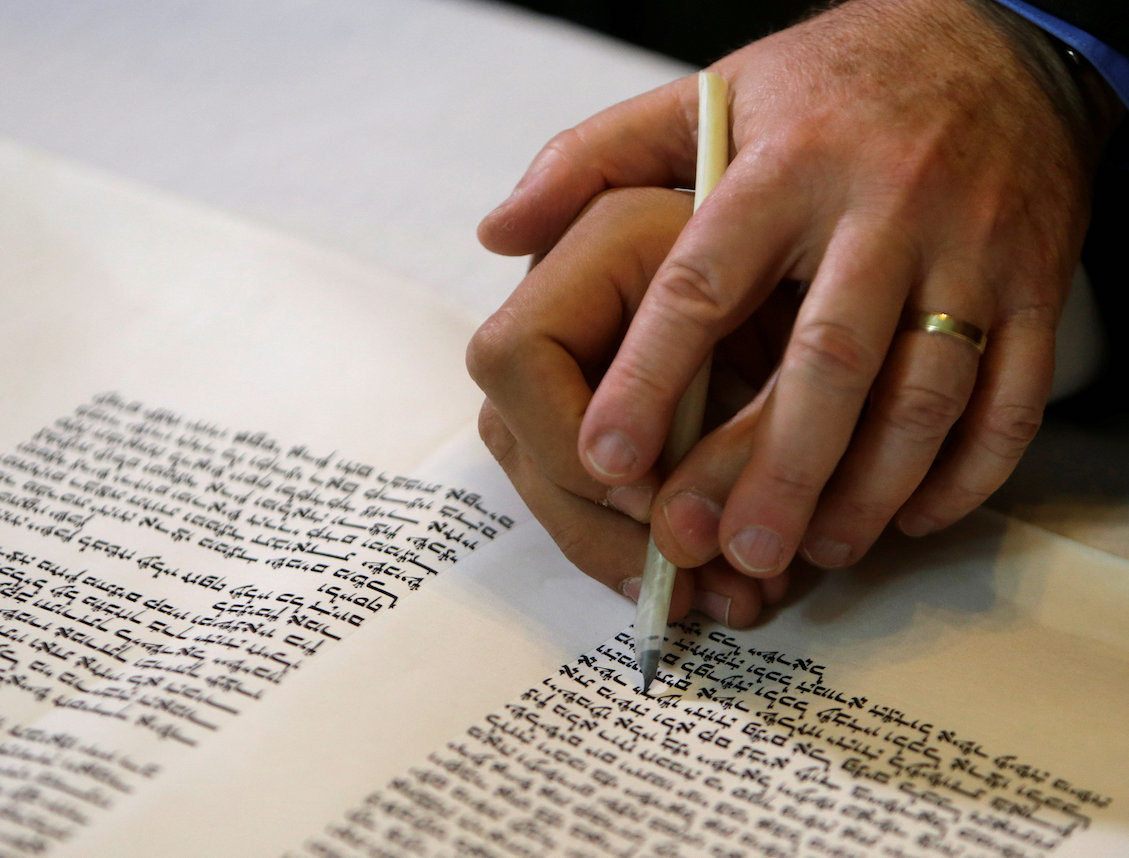

Reuters/David W Cerny

Reuters/David W Cerny To raise or to lower? That is a crucial question for a person to consider regarding how one’s spiritual life impacts other people and the world itself.

Do I wield my Judaism, my Torah, my very being in a way that raises others up? Or pushes them down? And even when I am down, knocked to the floor by others, do I muster the character to help others soar? Or do I use my power, influence or rage in order to stomp?

Within a religious community for which the notion of aliyah is so ubiquitous and resonant — whether with respect to being called to the Torah, or moving to Israel, or even what one hopes for one’s soul after death — attuning our daily encounters toward contributing to others’ ascent needs to be a more prominent part of a Jew’s life.

We learn this message from Korach and his anti-heroism in this week’s parsha. Many have pointed out that the content of his complaint against Moshe has merit; after all, Moshe and Aharon seem to set themselves above the rest of the congregation. It appears that all Korach is trying to do is to democratize the spiritual and political life of ancient Israel, and have all be equal before God — not a terrible goal. And yet, how he goes about it reveals more venal motivations.

Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner, the 19th-century Chasidic master, makes this point in his Mei HaShiloach. He quotes a midrash that imagines a circular geometry governing God’s relationship with all people; each of us is along the circumference, equidistant from God at the center. That, according to the Izhbitser Rebbe, is what Korach is claiming he envisions for Israel. And yet, when Korach and his fellow Levite clan members are themselves offered greater authority and access, they do not demur. Rather, they embrace the hierarchy. This suggests that Korach’s true intent was not to democratize or flatten hierarchy, but rather invert it. They didn’t just want themselves to rise. They wanted others to fall. They wanted to be at the peak, at the expense of others’ descent.

This is hinted at within the vocabulary of the opening lines of the drama. Korach accuses Moshe of lording over the congregation of Israel. The Hebrew is “titnas’eu,” from the root n-s-a, meaning to rise. Some translations have Korach complaining against Moshe’s “exalting himself” over the other Israelites. Is Korach recognizing something true about Moshe? Or is he perseverating upon rank and status because that is the only relational language he understands?

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel pointed out that we are most able to identify, and be troubled by, the very flaws in others that we, perhaps unconsciously, struggle with ourselves. Korach notices Moshe’s communal stature and height because Korach wants to be high and of status. Korach critiques Moshe, though deep down he envies Moshe and determines the only way for him to rise is for Moshe to fall.

How tragic. And how common, in more than one sense of the word.

This stance is in contradistinction to Moshe’s own modeling. Just two weeks ago, within Parashat Beha’alotecha, Moshe is brought quite low by the people’s clamoring accusations and insults — even from his own siblings. Nevertheless, he uses his audience with God not to raise himself at others’ expense, but rather to argue on behalf of his constituents and then pray that Miriam be healed, that she be raised up.

Can we reach that level? Ought we not at least aspire to it? Perhaps this aspiration should be a daily meditation. An early version of the siddur, comprised by Rav Amram Gaon in the ninth century, includes something along those lines. “May it be your will, Adonai our God, that you grant us a good heart and a generous spirit, humility and modesty, and good companions.” The Hebrew I have translated as “humility and modesty” is ruach n’mukhah and ruach sh’falah, perhaps better rendered as a “short” and “low” spirit.

I don’t think Rav Amram was praying that Jews go through their days debased and humiliated, heads slung low. Rather, the prayer was that we resist the urge to constantly climb higher, particularly on the backs of others’ decline. Perhaps that is why “humility and modesty” are so closely associated with “good companions.” When we use our voice, words and spirit to bring others higher, rather than lower, we will grow in friendship, we will grow in the stature that matters most, and we will grow the community in which we live.

Our times are fraught. On issues domestic, geopolitical, religious, status-based, Israel-focused and beyond, people are taking sides and staking claims more vociferously than I can remember. Perhaps the era calls for particularly strong stances in defense of the just. But strength need not be exhibited only via stridency. Truth and goodness have their own power, without the aid of battering rams. We ought to articulate our convictions with both confidence and humility. In eschewing Korach and emulating Moshe, may our very beings be an aliyah and lead most pointedly to the rise of righteousness and the ascent of the others in our midst.

Rabbi Adam Kligfeld is senior rabbi of Temple Beth Am (tbala.org), a Conservative congregation in West Los Angeles.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.