Md Saiful Islam Khan/Getty Images

Md Saiful Islam Khan/Getty Images As part of Women’s Healthcare Month, on May 23, MAVEN presented a conversation on “Life, Love and the BRCA Mutation.” MAVEN is the immersive and experiential digital learning platform of American Jewish University (AJU).

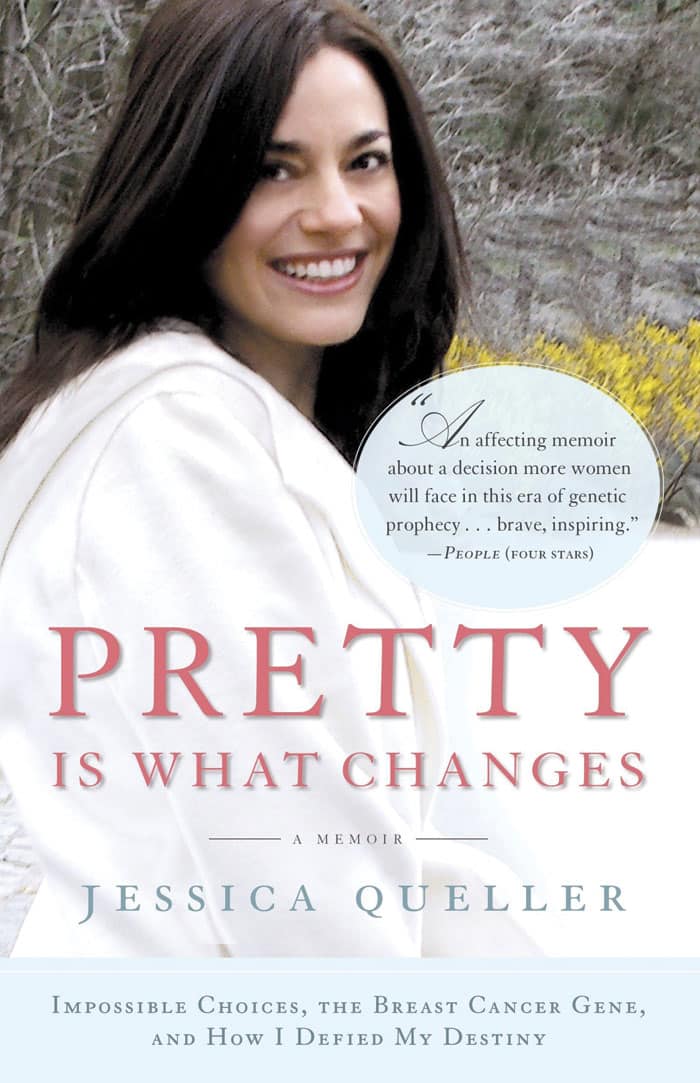

The webinar, hosted by AJU’s Catherine Schneider featured Jessica Queller, author of “Pretty Is What Changes.” The memoir chronicles her journey of inheriting a BRCA1 mutation from her mother and how it changed her life. Jenna Fields, chief regional officer of Sharsheret, also joined the conversation. A national Jewish nonprofit, Sharsheret supports women and families facing breast and ovarian cancer, as well as hereditary risk for cancer.

During the webinar, Queller reflected on her mother’s death and how writing the book was a coping mechanism, part of her healing process and a way to honor her mother. Queller shared the challenges she faced during that time. She also talked about her decision to be a single mother, how she re-met and found love with her husband and more.

During the webinar, Queller reflected on her mother’s death and how writing the book was a coping mechanism, part of her healing process and a way to honor her mother. Queller shared the challenges she faced during that time. She also talked about her decision to be a single mother, how she re-met and found love with her husband and more.

A television writer/producer, Queller has spoken about BRCA extensively on television and radio, has written Op-Ed pieces on the subject for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal and is a member of Basser Center for BRCA’s Advisory Board.

“I deeply identify with the [Jewish] community, my faith and my passion to help other women,” Queller said.

She lives in Los Angeles with her husband, Bill Prady, daughter Sophie Queller and stepson Asher.

“I took care of my health early, had a baby on my own, and then got married later,” Queller said. “It wasn’t the typical order, but it all worked out beautifully.”

One in 40 Ashkenazi Jews (men and women) carries a BRCA gene mutation. That’s nearly 10 times the rate of the general population. As Jewish families are significantly more susceptible to hereditary breast cancer and ovarian cancer, the webinar served as a friendly reminder to empower yourself for the sake of your health.

“This is such a Jewish issue on the health side and on the mental health side,” Fields said. “Any family history is worth looking into. All Ashkenazi Jews should be on high alert.”

Queller tested positive for the BRCA gene mutation in 2004, eleven months after her mother succumbed to cancer. Schneider remarked that Queller was likely the first person to publicly grapple with BRCA.

A friend suggested Queller was eligible for the BRCA test. At the time, the test for the BRCA mutation was 10 years old. Queller was 34.

Queller decided it would confirm her clean bill of health, and managed to get a lab order without any pretest counseling. When Queller got the call that she tested positive, the tech told her, ‘You are statistically assured of getting cancer. Go find some help. Good luck.’

Those positive results put Queller at a terrifyingly elevated risk of developing breast cancer before the age of 50 and ovarian cancer in her lifetime. (She would have to have her ovaries removed by age 40).

In her 30s, unattached and yearning for marriage and family, Queller faced an agonizing choice: a lifetime of vigilant screenings and a commitment to fight the disease when caught or the radical alternative: a prophylactic double mastectomy.

“Seeing my mother’s suffering and death, it was a clear decision to take the prophylactic action,” she said. “I had no tolerance for risk.”

Queller said the fear is much scarier than the reality. And the relief she felt when taking action is immeasurable.

Queller said the fear is much scarier than the reality. And the relief she felt when taking action is immeasurable.

“All of us who have gone through adversity [know] you rise to the occasion because you have no choice,” Queller said.

Fields made it clear: Mastectomy and ovariectomy (removal of ovaries) are an option, but are not something everyone who tests positive has to do. Many people choose to enter into a screening plan, Fields added, although there’s no good choice for ovarian screening.

Keep in mind, Quellers’ experience is not what people go through today, Fields told her.

”Now it’s easier and more affordable to test for a whole panel of mutations,” Fields said.

Those who test positive, or need to get tested, should know that they are not alone.

“Being your best self advocate is the best thing you can do,” she said.

Fields’ recommendations: Connect with Sharsheret’s genetic counselor, find the right team (there are resources and medical centers everywhere) and join Facebook groups and other communities for peer support.

Something everyone can do is open the lines of communication, when it comes to BRCA.

“Talk to a couple people about BRCA, genetic mutations and cancer risk,” Schneider said. “Let’s try to raise awareness in our communities and in our own homes.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.