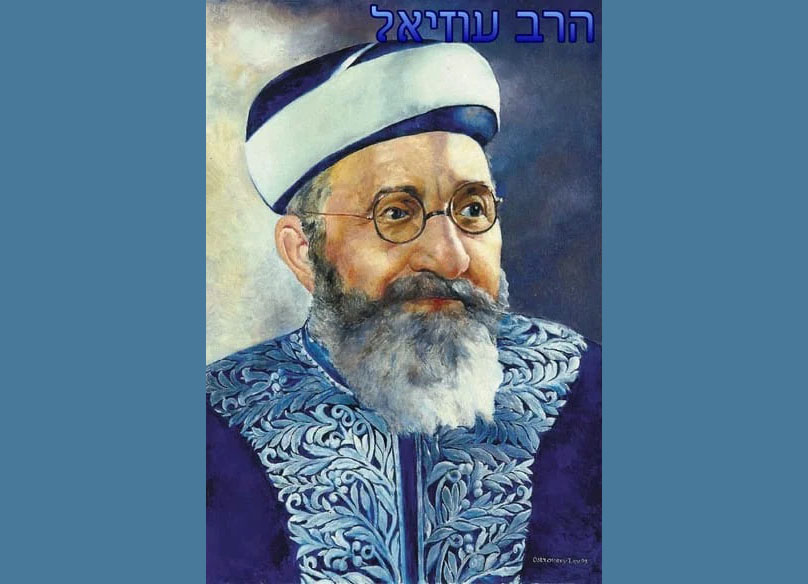

When Ahuva Goldstein attended Yeshiva Rav Isacsohn Torath

Emeth in 1960, she had five students in her sixth-grade class. The ultra

Orthodox elementary school was in its seventh year, but it did not have its own

building; it was housed in a synagogue on the corner of Third Street and Edinburgh

Avenue. The class was so small that it was combined with the seventh grade,

bringing the total number of girls up to 13.

“I don’t even think there were 50 students in the whole

school,” said Goldstein, 55, who now lives in Hancock Park and works as a

volunteer for Bikur Cholim and Hachnassas Kallah of Los Angeles. “But there was

not much of a choice [in Los Angeles] as far as the kind of in-depth religious

school my parents wanted. The education was very one-on-one, and we knew every

student. The teachers were very motherly, but it was really more like a little

house, with 30 to 40 kids running around, than a proper school.”

These days, two of Goldstein’s grandchildren attend Toras

Emes (as it is more commonly known) and she says the school has become “a whole

kingdom.” Celebrating its 50th anniversary on March 9, that kingdom includes

1,100 students in preschool to eighth grade, 240 staff members, five different

buildings in the Beverly La Brea area and an annual budget of $6 million.

Over the past 50 years, the school’s growth has been

synchronous with the expansion of the ultra-Orthodox community in Los Angeles

as a whole. In the 1950s, there was only a handful of synagogues that served

the ultra-Orthodox community, and even fewer schools. Today, the ultra-Orthodox

community has dozens of synagogues, several kollels and other community

infrastructure.

For many in the ultra-Orthodox community, Toras Emes is the

only educational choice worth considering: It serves as the middle ground

between the Chasidic Cheder Menachem (where secular studies are minimal) and

Ohr Eliyahu (a newer ultra-Orthodox school whose student bidy is more diverse).

What sets Toras Emes apart from other yeshivas in the city are, among other

things, its insistence on a high level of religious observance in the families

it serves. The school will not accept anyone whose parents aren’t Sabbath

observant and will not accept a child whose mother wears pants. Most Toras Emes

parents come from the far-right end of the religious spectrum and, according to

Toras Emes administration, 30 percent of its students are the children of

parents who are religious functionaries in the community, meaning that even

those who work in other places still consider Toras Emes to be the final word

in children’s education.

“Almost the entire [Jewish studies] teaching staff of any

Orthodox school in Los Angeles send their children here,” said Rabbi Yakov

Krause, the school’s principal since 1977. “So in a sense, we view our yeshiva

as a catalyst for Yiddishkayt in the entire community.”

The school takes Yiddishkayt very seriously, in intensity of

the learning and the number of restrictions it places on its students and their

parents to safeguard that learning. Torah is taught the first half of the day

to show its importance: School starts at 7:30 a.m. and Jewish studies continue

until 2:30 p.m. The chinuch (education), at Toras Emes is both old-style and

modern. In one second-grade Chumash (Bible) class, for example, many of the

students stand at their desks, their fingers pointing to the words in the

Chumash, swaying back and forth with their feet planted on the ground in

imitation of Rabbi Shmuel Jacobs, who is doing the same thing. In unison, they

repeat the verses of the text in a lilting cadence, first in Hebrew and then in

English. The effect is reminiscent of old European cheders, but before it

becomes too old-fashioned, Jacobs, a recipient of a Milken educators’ award,

turns off the overhead lights and switches on a moving electric light display,

which he has programmed to give the students information about the clothes worn

by the priests in the Temple.

In other classes, teachers discuss the finer points of

Hebrew grammar, connect the impending war in Iraq to the story of Purim and

find cute acronyms to get the girls to remembers the order of the animals that

lined the steps of the altar in the Temple. In the older boys’ grades, students

sit in a large beit midrash and learn Talmud chavrusa-style, with each boy

learning with a partner.

“We try to make the learning exciting for them,” Krause

said. “This is a time when we have so many distractions — the outside world has

so much glitz and glamour to it — that if the learning is just cut and dried —

and it doesn’t become alive to them — it’s a losing battle.”

The school tries to keep the outside world at bay with its

rules and regulations. Girls are required to adhere to the laws of modesty in

and out of school, and failure to do so is grounds for dismissal. Movie

theaters, regardless of the rating of the film or the accompaniment of an

adult, are off-limits. All television viewing is discouraged, as is patronizing

public libraries, and the school handbook states that the Internet “should be

treated like a loaded firearm.”

“If this is too much a price to pay for the chinuch we

provide,” the handbook continues, “then our school is not for you.”

Over the past half a century, Toras Emes has indeed

established itself as a vital institution for Los Angeles’ ultra-Orthodox

community, and yet, its phenomenal growth has not come without costs. The sheer

size of the school, some say, creates one large culture where individual needs

are not met. And with the generous amount of financial assistance it provides

(only 350 of 1,100 students are full-fee paying), some say the school doesn’t

have the resources to accommodate all the students.

Yet, the school says that while it is inevitable that some

students will get lost in the shuffle despite the school’s best efforts, it has

never sacrificed educational quality for financial reasons.

“I don’t think the education has been affected [by the

financial situation]. Nothing has been stopped because of money,” said Rabbi

Berish Goldenberg, also a principal and a fundraiser for the school.

Goldenberg cites the small classes, and the inclusion of

special needs staff as evidence of the school’s efforts to deal with its

imposing size.

As the school gets larger, different questions arise about

its direction. Should the school move more to the right? Should the school

become a television-free school (meaning that parents will need to get rid of

their sets before enrolling their children in the school)?

As a way of dealing with some of these issues, the school

has a “cheder track” for the younger grades, where Jewish studies are taught in

Yiddish. While some parents don’t particularly care for the Yiddish, they still

want their children in the cheder track, because it’s for children from more

seriously religious homes — homes that do not have televisions, and where

there is no ambiguity in their commitment to Torah.

Even with these issues, many parents feel that what their

children get out of Toras Emes is priceless.

“Toras Emes is not so much about the education,” said

Jonathan Weiss, who attended the school, and whose two children are students

there. “The students are imbued with traditional Jewish sensitivity and

feelings, and it becomes their essence. I think that is why parents send their

children there.”

“I have yet to meet a mother who doesn’t have something to

complain about when it comes to the education of their children,” said Batya

Brander, mother of three Toras Emes students. “But the love of Judaism that my

kids have from Toras Emes is indescribable, and that far outweighs everything

else.” Â

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.