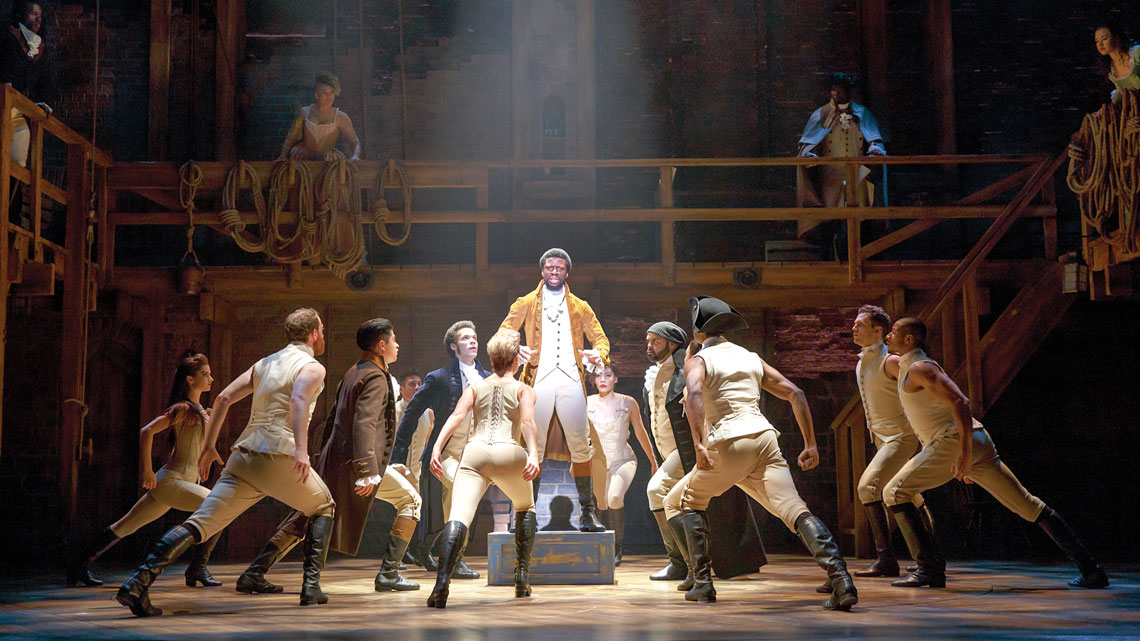

Founding Father Alexander Hamilton was many things: statesman, lawyer, banker and Secretary of the Treasury, to name a few. With the Tony Award-winning success of the hip-hop musical “Hamilton” — now playing at the Pantages Theatre in Los Angeles — he’s also a modern pop culture icon.

But according to historian Andrew Porwancher, associate professor of constitutional history at the University of Oklahoma, Hamilton may have been something else: Jewish.

Porwancher, who holds degrees from Northwestern, Brown and Cambridge universities, has uncovered multiple sources of evidence that the man on the $10 bill was a member of the tribe. He’s compiling the information for a book titled “The Jewish Founding Father: Alexander Hamilton’s Hidden Life,” scheduled to be published by Harvard University Press in 2019.

While examining Hamilton’s Caribbean-island childhood as he prepared for his lectures, Porwancher learned that Hamilton attended a Jewish school on Nevis, a British colony. Further research suggested that Hamilton’s mother, Rachel, may have converted to Judaism when she married Danish merchant Johann Michael Lavien. She was still married to Lavien when she and James Hamilton conceived their son and gave birth to him in the mid-1750s (the exact year is disputed).

“No Hamilton biographer before me has taken seriously the idea that Alexander Hamilton might be Jewish according to Jewish law,” said Porwancher, an Ashkenazi Jew who grew up Conservative in a kosher home and is affiliated with the University of Oklahoma’s Judaic Studies Department.

“I’ve dedicated years of my life to studying Jewish history and I’m definitely very connected to Judaism,” he said.

Porwancher’s first step in researching Hamilton’s connections to Judaism was to determine the likelihood that Johann Michael Lavien was indeed Jewish.

“For generations, scholars have erroneously assumed that because [Lavien] was not identified in Danish land or census records as a Jew, he must not be Jewish,” Porwancher said via phone from London, where he was continuing his research.

Records in the National Archives of Denmark, which had colonized the Caribbean island of St. Croix, indicated that other known Jews living on the island also were not identified as Jewish. “So the assumption Lavien was not Jewish based on the records is erroneous,” he said.

Porwancher said the name Lavien is a specifically Jewish name, and Danish Christian surnames at the time, by contrast, were patronymic (derived from the name of a father or ancestor) and typically ended in “sen.” Other clues included that Lavien was a merchant, a popular trade for Jews, and that Alexander Hamilton’s grandson referred to Lavien as “a rich Danish Jew.”

Other evidence indicates Lavien wasn’t Christian, Porwancher said. Before Hamilton was born, Lavien and Rachel had a son, Peter, who was not baptized, even though baptism was standard practice for Christians on St. Croix.

“That’s evidence that not only was Lavien Jewish, but Rachel converted to Judaism to marry him,” Porwancher said. “I studied 18th-century Danish marriage law and discovered that Jews and Christians were not legally permitted to marry absent of conversion. So if Lavien was Jewish, the law would have required Rachel to convert to Judaism, explaining why their child wasn’t baptized.”

No baptismal records exist for Alexander Hamilton or his brother, James Hamilton Jr., either, but Porwancher believes it had nothing to do with their illegitimacy.

“We can find records around the Caribbean of children born out of wedlock who were baptized and could have attended a church school,” Porwancher said. “The fact that Alexander Hamilton went to a Jewish school rather than a Christian one is compelling evidence that he was seen as a Jew by the Jewish community in Nevis,” where he lived until the age 10.

“It strains credibility that this Jewish school would have taken in a child that they believed to be Christian,” Porwancher said. “His teacher would stand him on a table to recite the Ten Commandments in the original Hebrew. Bear in mind that there’s a talmudic prohibition against Jews teaching non-Jews the Torah.”

Porwancher further noted that the listing of Rachel Lavien’s 1768 death in a church register doesn’t mean she was Christian or had returned to Christianity.

“Churches would record the births and deaths of nonmembers, even Jews, particularly in a place without a synagogue like St. Croix,” he said. “Rachel isn’t buried in a church cemetery, but on the estate where her sister lived.”

Another phase of Porwancher’s research has focused on Alexander Hamilton’s relationships with Jews in his adult life. Although the adult Hamilton has never been found to explicitly identify as Jewish, he was remarkably outspoken in his defense of Jews, he said.

“Among the Founding Fathers, Hamilton was singular in his advocacy for American Jewry,” Porwancher said. “He represented a variety of Jewish legal clients. He teamed with Jewish merchants to help create the American financial system. He fought anti-Semitism in court. And thanks to Hamilton, his alma mater, Columbia University, had Jewish representation on its board for the first time: Gershom Seixas, the head of Shearith Israel, the oldest continuous Jewish community in the United States.”

Porwancher first thought about writing a book about Hamilton in 2013, but other commitments prevented him from delving further into the topic until January 2015. A month later, “Hamilton” opened at the Public Theater in New York City, and by the time it moved to Broadway that summer he was shopping around a book proposal and a sample chapter.

Porwancher saw a preview of “Hamilton” on Broadway and said the musical “does a better job than most historical scholars of understanding the centrality of Hamilton’s Caribbean origins to who he was in his adult life.”

While the show doesn’t make any reference to the potential Jewish aspects of Hamilton’s life, “I can’t hold that against Lin-Manuel Miranda,” who wrote the musical, Porwancher said. “But I do think the story of Hamilton’s Jewish origins dovetails with the spirit of the musical. They’re both attuned to the ways his Caribbean origins informed his adulthood.”

Porwancher continued: “A lot of the academic scholarship on Hamilton sees him as this wannabe aristocrat. But the musical, with this multiethnic cast, portrays his history as much more democratic. He believed in an aristocracy of merit, and that in this new American republic, a Jew and a gentile should stand equal before the law; and no matter one’s faith, one should have the opportunity to fulfill the full measure of one’s potential.”

Currently in London to research source material from Nevis at the British National Archives, Porwancher said he has a lot more investigating to do to complete his book.

“Writing the history of someone’s childhood in the Caribbean in the 18th century is a difficult enterprise because you’re required to use primary sources in multiple languages that are scattered across islands and European capitals of the countries that colonized those islands,” he said. “So it’s not a surprise that key elements of Hamilton’s childhood remain obscure today. The task of re-creating his earliest days is in many ways more difficult than understanding the origins of any other Founding Father.”

Porwancher will be on sabbatical this year to continue his research while doing a fellowship at Yeshiva University this fall and another at Princeton University in the spring.

He hopes people will approach his book with an open mind, and will “be amenable to the idea that there could be something significant about a well-known historical figure that we don’t yet know.”

Noting that scholars didn’t believe that Thomas Jefferson had fathered children with the slave Sally Hemings until DNA tests and historical evidence proved it to be true, Porwancher thinks that Hamilton’s history can be rewritten too.

He also hopes that people “see in the story of Hamilton not only the history of the Jewish experience in America, but the history of the immigrant experience writ large — the story of wanderers who come to a new homeland in search of a better life.

“It’s not just the heart of Hamilton’s story that Lin-Manuel Miranda captured so well, or the Jewish American story,” he said. “It’s the American story, period.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.