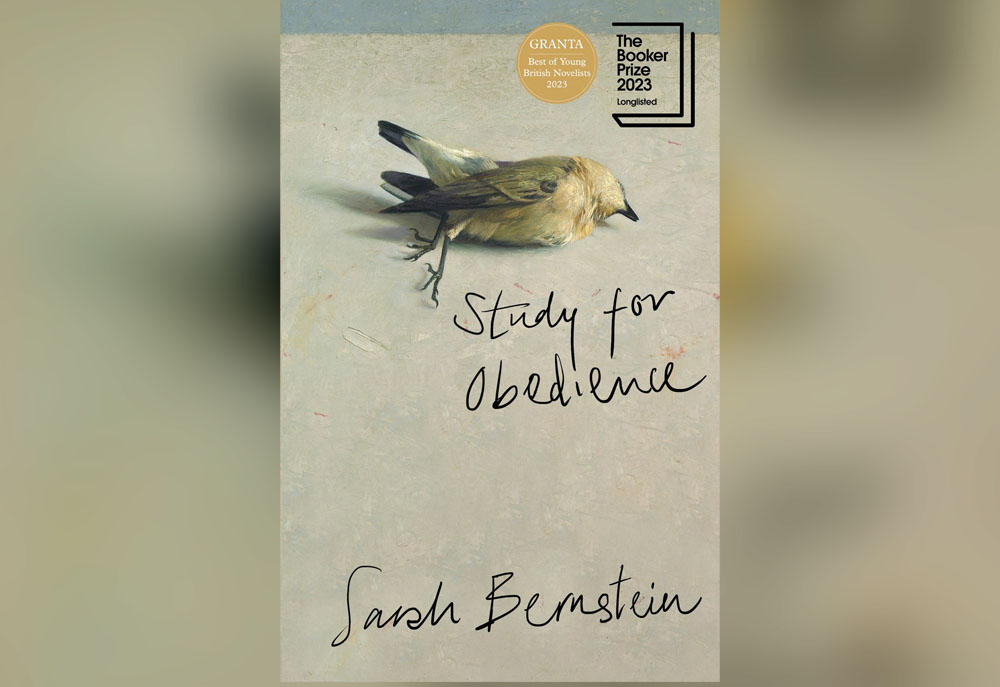

In a recent talk I attended, Sarah Bernstein, one of Granta’s “Best of Young British Novelists” of 2023, said that she would prefer that readers come away from her novels with questions rather than answers.

If this was her great hope with “Study for Obedience,” she succeeded.

“Study for Obedience” is about an unnamed narrator who travels to an unnamed place and either acts upon or is acted upon by the new setting. She is there to tend to her unnamed brother, who was likely abusive and who becomes ill under her care. The story takes place in the narrator’s head; there is no dialogue. We know that the narrator is clearly Jewish—not that this word is ever used—and probably comes, like the author, from Canada. It could as easily be the United States, but we are all prone to projecting the author into a first-person narrator, and the use of the phrase “none is too many” will send a small shiver down the back of any Canadian Jew, knowing that these were the words uttered by the Canadian minister of immigration in 1939 when asked how many Jews would be allowed into Canada after the war. The nameless country to which the narrator relocates is where her ancestors were from, where they were reviled and eventually “put into pits.” One imagines Babi Yar, but there were many Babi Yars; my own ancestors were thrown into pits in Górka Połonka.

This narrator is self-effacing, almost literally so. Airport sensors don’t register her presence. It is as though she is a ghost. And like a ghost, she haunts the town, cycling and walking through the lands by night, leaving strange woven dolls at the homes of locals. Bad things start to occur. The return of the repressed—a modern-day, ghostly Jew—sends the townspeople into a state of fear.

“Study for Obedience” is a short book—barely two hundred pages, with much white space on each page—and my own copy arrived misbound. I didn’t realize this fact at first, but as I read a sentence that began on one page and continued onto the next, I found myself lost, and I had to start over. Initially, I attributed the strange syntax to the warped mind of the narrator, and I moved along. Soon after, it occurred to me that the narrator was repeating herself, though this point, too, didn’t seem entirely out of keeping with the novel’s logic. Finally, I noticed that my edition went from page 103 to 39. Aha!

I ordered a new copy.

It, too, was misbound.

I mention this aberration only because I almost wonder if it was an aberration at all, or rather if there was something deliberate in the shuffle of pages—if the author or publisher wanted to make a statement about time, past and present, never staying in order. Because that is certainly a message (or question) of the novel.

But there is also something else at play in “Study for Obedience.” The opening lines feel tauntingly like “A Fable for Tomorrow,” the opening passage of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” the 1962 landmark book that launched the environmental movement. Imagining at first an idyllic land, Carson writes: “A strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change … mysterious maladies swept the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died.” Similarly, Bernstein begins “A Study for Obedience” by telling us that “the sow eradicated her piglets,” crushing them to death. A local dog had a phantom pregnancy. Cows went mad (and are shot and put into mass graves). A lamb became stuck mid-birth by a trapped ewe and remained half-emerged from the ewe’s body, its eyes pecked out.

Carson’s fable closes with an indictment: “No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it to themselves.”

So, too, we might think, did the people in this unnamed land create their own blight. For although they had “lived through a blessed and prosperous fifty years,” allowed to be connected to the place since time immemorial, conveniently removing from memory or history the roles their people played in the lives of the narrator’s people, we might say that when the land and animals turn on them, “the people had done it to themselves.”

This dark, absurdist, often confusing novel is not for everyone.

This dark, absurdist, often confusing novel is not for everyone. It is wretched to be trapped in the head of a narrator who is relentlessly unreliable and very unlikeable, who embodies, following the artist Paula Rego’s “Obedience and Defiance” exhibition, two extremes. The narrator takes empathy to its (il)logical end, seeing the self (a painfully abject figure) and her victimized people in the eyes of perpetrators, deserving blame, deserving death. And at the time, we suspect that she herself is a kind of perpetrator, terrorizing not only the townspeople but also her ill, immobilized brother-patient (think Kathy Bates in “Misery”).

But for all that, “Study for Obedience,” which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is not a novel soon forgotten. It takes a very talented writer to take hold of a reader who (along with townspeople and brother) finds herself wishing desperately to escape the narrator’s clutches.

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.