In contemplating gratitude, author Eckhart Tolle wrote, “Acknowledging the good that you already have in your life is the foundation for all abundance.” From time to time, we read true-life stories that recount the pain of others and are left feeling sad, anxious or hopeless. But rare is the telling of a story that leaves us feeling wholly compassionate for the pain someone has endured, while infusing us with a flood of renewed gratitude (and even awe) for our own abundance. In his inspirational novel, “The Lip Reader,” Michael Thal enables us to experience the nexus of deep compassion and wide-eyed gratitude through the journey of a woman who ultimately frees herself from the emotional burdens of her physical limitations.

“The Lip Reader” tells the story of Zhila Shirazi, an Iranian Jew who, at the age of three, loses hearing in both of her ears as a result of meningitis. Readers soon learn that for Zhila and millions of others worldwide, deafness is often treated as a miserable liability. “In my country of Iran, a disability is a curse,” Zhila says early in the novel. She adds, “People with disabilities in mid-20th century Iran were considered tragic and pitiful. Those afflicted were seen as unfit or even feeble-minded and incapable of contributing to society. Their worth was only valued as entertainment in a circus sideshow or as objects of scorn. Many disabled individuals were forced to undergo sterilization so as not to pass disabling genes to their offspring.”

Zhila struggles with deafness her whole life, but always strives to make peace with her disability. The book’s themes of escaping the metaphoric prison of society’s harsh confines, as well as peace with oneself as the ultimate emblem of freedom, is especially inspiring during Passover.

In real life, Zhila Shirazi (a fictional name) was Thal’s beloved partner of 16 years, a Tehran-born Jewish woman named Jila whom he met in 1999.

Thal writes in the first person as Zhila, an impressive feat given that, as an Ashkenazi man, he manages to capture the voice of an Iranian Jewish woman with nuance and authenticity. But this achievement is rooted in experience: In real life, Zhila Shirazi (a fictional name) was Thal’s beloved partner of 16 years, a Tehran-born Jewish woman named Jila whom he met in 1999. In 2010, Jila was diagnosed with colon cancer. She passed away in 2015 at age 65, leaving Thal broken with heartache.

To help cope with his grief, Thal decided to write Jila’s story, a process that took four years and the help of Azin David and Dr. Juliet Hananian, both Iranian American Jews who helped guide Thal’s research. In writing “The Lip Reader,” Thal freed himself from some of the overwhelming grief that threatened to shackle him to despair for perpetuity. “I was prepared to tell Jila’s story, the story she told me,” Thal told the Journal in an email interview. “A year after Jila died, I met my in-laws at the cemetery for the unveiling of her headstone. I had spent the past year crying, depressed and missing my Jila terribly. I thought I could bring her back if I wrote her story. I thought using her voice would be the best way to go about doing that. It was the hardest book I ever wrote.”

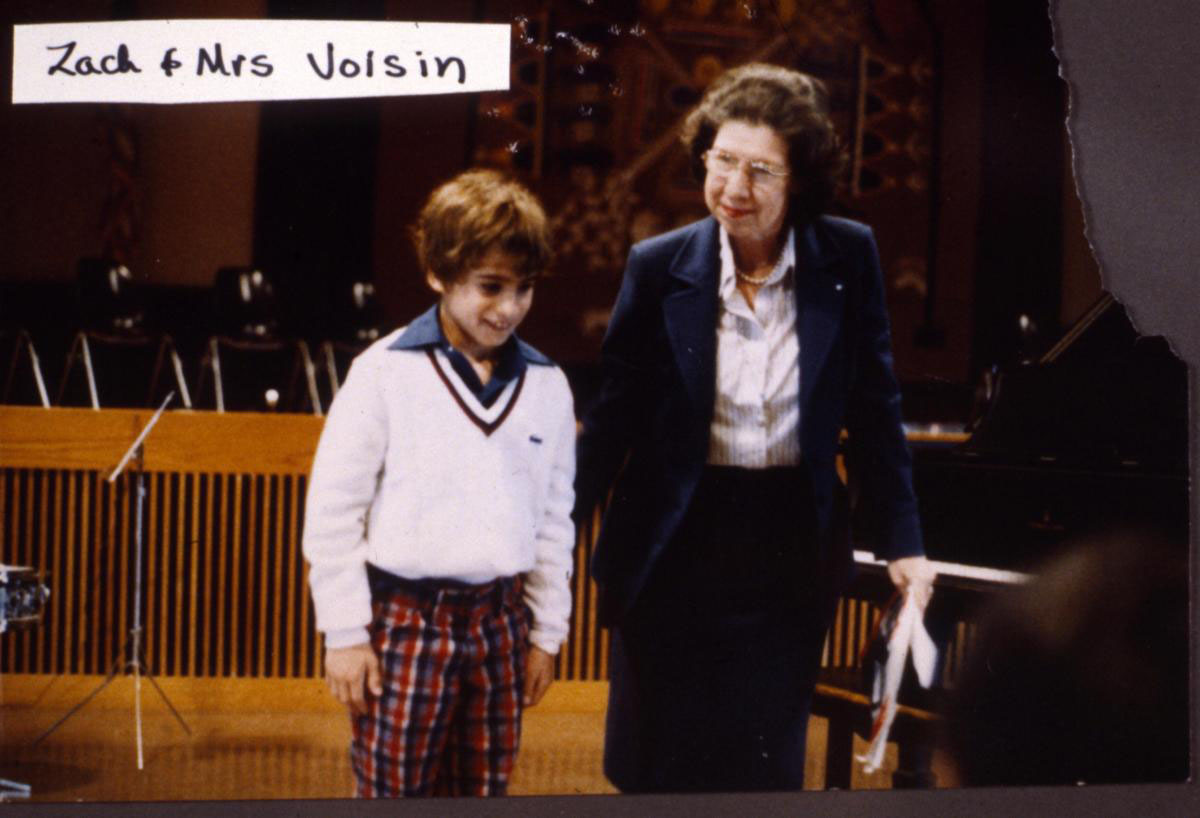

A former Glendale Unified School District teacher, Thal awoke one morning at age 44 with severe bilateral sensoneural hearing loss (doctors diagnosed it as an overnight hearing loss due to a virus). His near deafness forced him to leave his tenured position as a sixth-grade teacher in Glendale and put pen to paper. Thal has written six books, including “Goodbye Tchaikovsky,” and authored over 80 articles. Born in Oceanside, New York, he studied history at University of Buffalo and completed his graduate work in Elementary Education at Washington University, St. Louis. Thal moved to L.A. in 1973.

During their time together, Jila told Thal her story in American Sign Language, the language the couple used to communicate with one another.

During their time together, Jila told Thal her story in American Sign Language, the language the couple used to communicate with one another. Set in Iran (beginning in the 1960s) and then the United States, “The Lip Reader” is a humbling series of stories about Zhila’s early life, the near-death dangers of living in post-revolutionary Iran and the incredible difficulty of immigrating to the U.S. and starting life anew. Some of the stories are true, while others are fictionalized.

In the book, which won the 2022 eLit Award for best inspirational novel, Zhila describes her desperate childhood wish to be tested and fitted for a pair of hearing aids. An intelligent and resourceful little girl, Zhila reads lips, but is unable to understand her teacher when the woman turns her back to write on the chalkboard.

Incredibly, Zhila faces a problem that makes her deafness even more painful: At her family’s insistence, she is forced to keep her disability a secret from her teachers, friends and even her relatives. As a result, her unknowing teacher physically and verbally abuses Zhila in class, believing she is deliberately not listening to instruction. The teacher, Mrs. Gaidi (another fictional name) stabs Zhila in her head with a pencil and shouts, “That should wake you up, you stupid Jew, now get out of my class and don’t come back until you learn respect.”

Her parents, Zhila explains, wanted to keep her deafness a secret because “they feared ridicule from the community for their inability to sire healthy, normal children,” and sadly, hearing aids, they surmised, “would be stark evidence of my inferiority.” When Zhila finally realizes her dream of being tested for hearing aids, she’s devastated to learn that the hearing loss in her right ear is too severe to be treated with such a device.

Again, readers can’t help but be moved by Thal’s heart-wrenching descriptions of a little girl’s wish for one of the most seemingly mundane, yet extraordinary senses that many of us take for granted: our hearing. Both Jila and Thal were born with hearing but lost this precious sense due to sudden illness. Their stories are a powerful reminder of the fragility of our own abundance.

When Zhila’s mother, Sara, is unable to buy expensive hearing aids, the child responds, “I will get a job! I will help pay for it!” When Sara still refuses, Zhila confronts her in the street with a desperate plea: “Maamaan! [“mother” in Persian] I want to hear music and laughter. I hate being so different. You do not want people to know! You are afraid they will gossip that your daughter is defective. God forbid they see a hearing aid and realize I am deaf!”

If living as a deaf girl and as a Jew in Iran weren’t difficult enough, the Islamic Revolution renders life wholly intolerable for Zhila and her family. One day, her father, Solomon, a pharmacist in Iran, is suddenly arrested and dragged away to the city’s notorious Evin Prison. The frantic family fears Solomon will be killed, but Zhila’s extraordinary intervention saves her father’s life. Still, the family is horrified when Solomon returns home badly bruised, traumatized from torture while in prison, and blind in both eyes.

According to Thal, this is based on a true story; Jila’s father was arrested, tortured, nearly killed and blinded by prison guards in post-revolutionary Iran. Amid such pain, the family’s survival is incredible. In fact, the stories of the 850,000 Jews who escaped or were forced to leave Arab and Muslim countries in the 20th century is one of the most powerful links in the millennia-long chain between the ancient Israelites’ exodus from Egypt and the mass exodus of Jews from inhospitable countries in the last 100 years.

The setback involving hearing aids nevertheless pushed Zhila to become a uniquely skilled lip reader. “Jila could lip read English as well as Farsi,” said Thal. “Most deaf people aren’t very good at lip-reading. They get about 30-40% of a conversation through their lip-reading skills. Jila got about 60%.”

The heartbreaking challenges of Zhila’s life only increase, as readers learn of the brutal discrimination she and tens of thousands of Iranian Jews faced even before the 1979 revolution that turned the country into a fanatic theocracy.

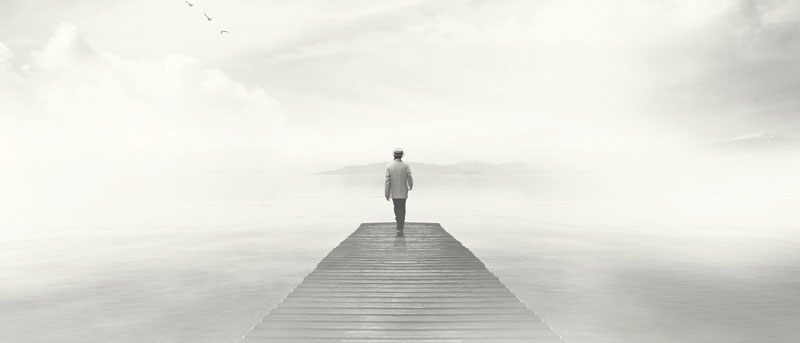

Zhila survives many painful hardships, but perhaps her greatest achievement is a quiet and elegant embrace of her deafness — a self-liberation that allows her to eventually experience the pleasures of life.

Zhila survives many painful hardships, but perhaps her greatest achievement is a quiet and elegant embrace of her deafness — a self-liberation that allows her to eventually experience the pleasures of life. Surrounded by many who seem to view her as deficient, Zhila manages to make her disability remarkably smaller. But her journey to embracing her lack of hearing is rooted in painful honesty. At one point, when discussing marriage, Zhila even tells her mother, “You think I will never find a good man because I am deaf.”

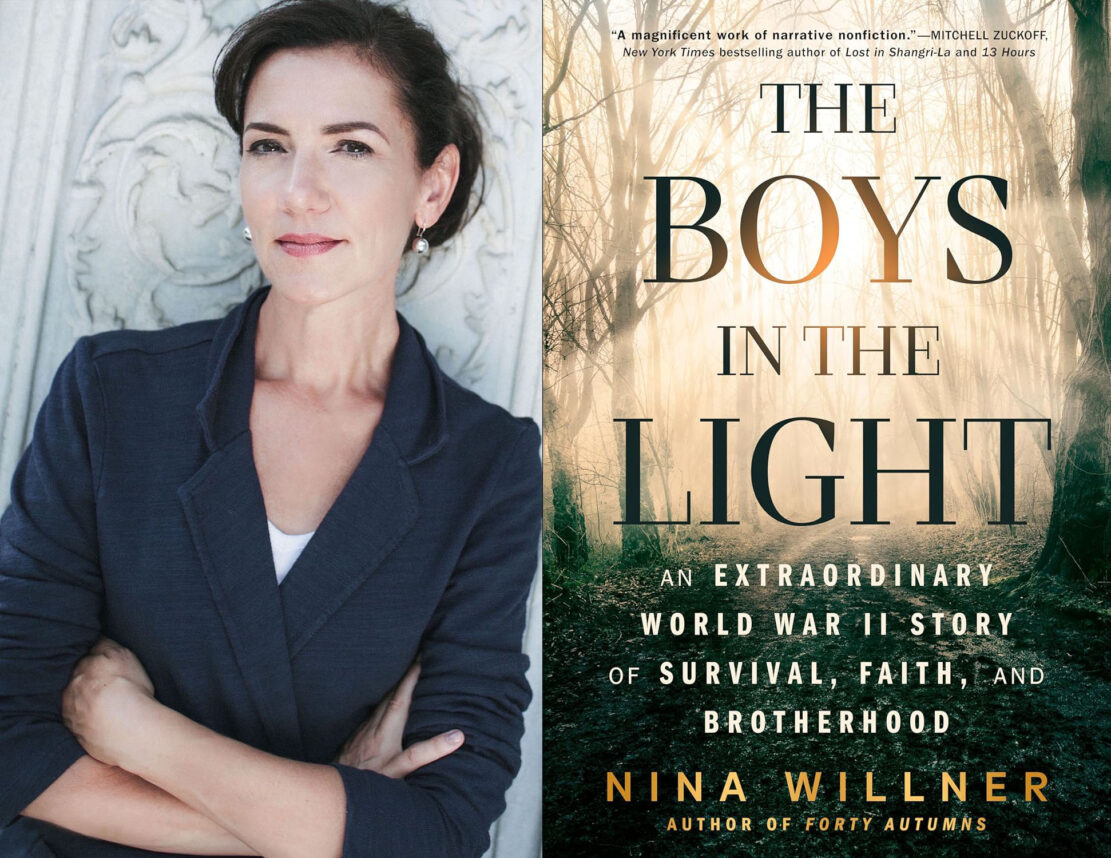

Photo from michaelthal.com

Inevitably, she does find a good man. After decades of hardship, Zhila finally immigrates to the U.S., where she meets the fictional Mickey, a Jewish divorcé who lost his hearing later in life and who falls in love with Zhila’s beauty, strength and resilience. Naturally, the character is based on Thal himself. When asked if he had difficulty remaining objective in writing about Mickey, Thal responded, “I didn’t have a hard time being objective; Jila had a few complaints about me, and I capitalized on them.”

Thal repeatedly asked Jila to marry him, but she declined, citing financial concerns. In her youth, she was struck by a car and suffered lifelong medical problems and back pain. In the novel, Thal captures the depth of the accident when Zhila tells readers, “These are the hazards of deafness. I live in a world of constant, watchful action. I must be observant because I cannot hear the sounds of danger.”

Thal knew that if Jila married him, she would lose her Medicaid health insurance. But during a trip to Hawaii to visit Jila’s childhood friend, the couple learned that ancient Hawaiians were not married by ceremony; many were married by promising to love and respect each other. Jila and Thal made this promise atop a serene Hawaiian mountaintop; to each other, they were husband and wife.

As the writer of Jila’s story, Thal maintains enough distance to also share some of her family secrets, though with enough changes to avoid disrespecting Jila’s living family members. For readers, it’s a satisfying decision, given the novel’s profound warnings about the burdens of maintaining secrets and the unique freedom that arrives with telling the truth about oneself. When Zhila is finally ready to tell others of her deafness, she does so with a sense of peace and confident elegance.

Jila’s story is also proof that redemption doesn’t occur overnight for those who arrive seeking freedom in America. Thal’s descriptions of the remarkable hardships Zhila and her family members endure when they resettle in Los Angeles, particularly by having to begin careers over again, are enough to make most readers appreciate how hard Iranian Americans and other immigrants have worked to start new lives in this country. It’s my hope that the book inspires particular appreciation for the Iranian Jewish experience in Southern California, home to the largest such diaspora community in the country.

As for Thal, he finds tremendous meaning in keeping Jila’s story alive, staying connected with his children (from a previous marriage) and through his involvement with Temple Beth Solomon (TBS), the world’s first synagogue for the deaf, based in Granada Hills. “My exposure to TBS has introduced me to other deaf people,” said Thal. “When Jila was alive, I didn’t need to meet other deaf people. Jila filled that need. After she died, I felt so alone.”

In the novel, Thal recounts the beginning and end of Jila’s cancer with profound honesty, though he admits, “writing about her illness was difficult. It was so hard to watch a vibrant, beautiful woman deteriorate. But through it all, she never complained. When she had the strength, she’d do what she loved to do most of all, help others.”

“The Lip Reader” proves that personal redemption is ultimately derived from within, and that retelling the stories of those whom we have lost is one of the greatest acts of love. Despite having witnessed her painful physical deterioration, Thal prefers to remember his beloved Jila’s most enduring traits: “She was sweet, kind, loving and she gave the best hugs,” he said. “Jila meant everything to me. Her sister used to say, ‘Jila and Michael were joined at the hip.’ She was right, and I’m still suffering from the unwanted amputation.”

“The Lip Reader” is available in trade paperback, hardcover, and digital, and can be purchased on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop, and IndieBound

Tabby Refael is an award-winning writer, speaker, civic action activist and weekly columnist for The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Follow Tabby on Twitter and Instagram @TabbyRefael