The Orthodyke is having something of a cultural moment.

There were lesbians in the important documentary “Trembling Before God” (2001), but I think the Orthodyke—the lesbian who lives somewhat freely, maybe even proudly in an Orthodox community—first entered the spotlight in 2006 when Naomi Alderman published “Disobedience.” That novel ends (spoiler alert) with a beautiful model of the Orthodyke, a kind of wise woman of her Orthodox community. It wasn’t the only possible conclusion; Esti’s fate plays out a different way in Sebastián Lelio’s 2017 film version, where religion and sexuality are treated as more of a zero sum game.

Now, the Orthodyke appears here and there and everywhere: she’s Malkie the self-proclaimed Orthodyke in “Sex and the City” creator Darren Star’s series “Younger,” hosting Sapphic Shabbat and having a blast with her fellow Orthodykes in the mikveh (it’s to Star’s Malkie I owe the term “Orthodyke”). She’s Noki, the lesbian bestie of the title character “Chanshi,” going on about her wild affairs in seminary on the new Israeli television series that features Henry Winkler (the Fonz in black hat! For real!). She’s Leah, the former Hasid, in the recent Danish horror film “Attachment” (2022), living in London’s Stamford Hill. As portrayed by the film, the Orthodox community might have a lot of issues (in particular, a very grouchy dybbuk); homophobia, however, is apparently not among them.

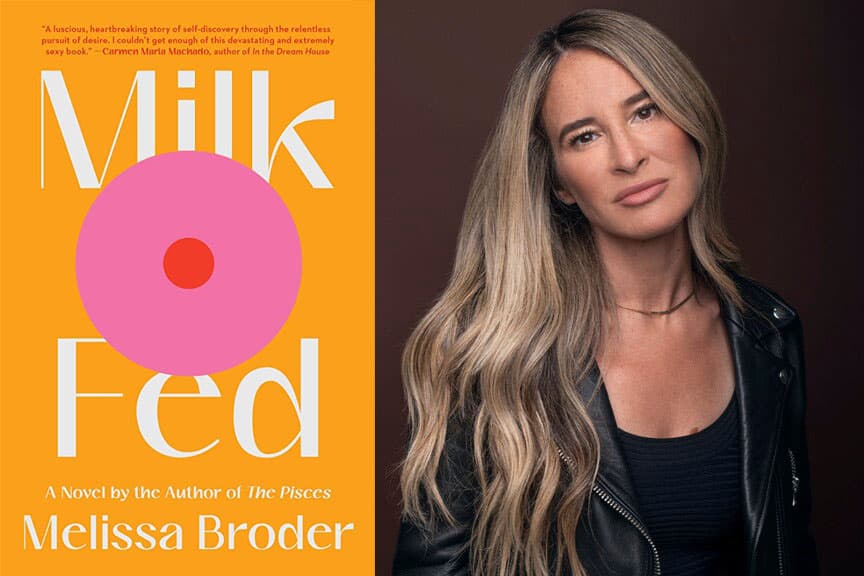

One of the hottest iterations of the Orthodyke I’ve encountered of late is in Melissa Broder’s intimate and erotic novel “Milk Fed.” Broder’s narrator, Rachel, is an East Coast transplant to Los Angeles, working at a talent management agency. Counting her calories in muffin tops and chopped salads, Rachel seems rather miserable at the start of the novel. She has an eating disorder, and she is always hungry. So it’s no surprise that attractive Miriam, the “zaftig girl” who wears long skirts and serves fro-yo, appears, in Rachel’s eyes, as a big, edible treat. According to Rachel, Miriam has pale lips like “pastel nonpareil white chocolates,” hair “the color of cream soda,” eyebrows “the color of lions, lazy ones … eating butter at night with their paws by lantern,” a tongue “like a piece of liver,” a beauty mark like “a caramel chip,” and moles like “milk chocolate drops.”

Through Miriam, whose freedom as an Orthodyke is, admittedly, constrained, Rachel is at last allowed to satisfy her desires—both culinary and sexual. In fact, Miriam is so much the embodiment of Rachel’s desires that Rachel begins to be unsure if Miriam is real. Real—or a golem? Or, as Rachel imagines it, a “challah golem”? Was Miriam, Rachel wonders, really a challah golem that “shook and shimmied back and forth as if beckoning me to come dance with it,” to rest “my face against the glazed crust, to dive into that eggy, doughy center headfirst”? With her challah golem, Rachel enjoys indulgent meals, sexual encounters, and dreams of Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the Jewish mystic attributed with the creation of the Golem of Prague.

Those familiar with Broder’s earlier work—she was primarily known as a poet before “Milk Fed”—might be surprised by the intense Jewishness of this novel. Beyond the golem legend, the references to Israel, and the Orthodox lifestyle portrayed in the novel, are those very Jewish and very conflicted messages about eating and staying slim. “Ess, mein kin,” my grandmother used to say, pushing bowls of chicken soup with carb-rich matzo balls in our faces, along with kugels and mandelbrodt. And also: “This is my granddaughter, kineinahora,” my grandmother would say, in such a way that my sister, all her childhood and teenage years, thought meant “This is my granddaughter, poor fat girl.”

Those familiar with Broder’s earlier work—she was primarily known as a poet before “Milk Fed”—might be surprised by the intense Jewishness of this novel.

The Orthodoxy of the novel is, however, a little muddled. After a meat dinner, Miriam goes to buy M&Ms. While Broder has her character recognize that people practicing kashrut need to wait before consuming dairy, Miriam’s announcement that “technically I should wait an hour … but I won’t” is surprising; typically only the Dutch follow this particular custom within Orthodox circles. Miriam’s father, unusually, sports peyos but no beard. His tzitzit dangles “from his pocket.” The family, we are told, was “ultra-ultra-Orthodox” in Monsey, but now “just modern Orthodox” in California (with peyos?).

Nonetheless, Orthodoxy is not depicted in the relentlessly horrible, and voyeuristic, light so common today. Although Rachel is an outsider, a cultural Jew, she doesn’t discuss it as though it were from Mars. It has its good, and it has its bad. Like everything else.

“Milk Fed” is a well-written novel—sensual, funny, sexy—but it can also be hard to read. By putting the novel in the first-person singular, Broder immerses her audience in the mindset of a woman with serious mental health issues; there is no doubt this book has the potential to be triggering to people who have experienced the trauma of eating disorders.

I should also say that if explicit sexuality is not your thing, this book about an Orthodyke is definitely not for you.

Karen E. H. Skinazi, Ph.D, is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.