“The Statement” opens in 1944 with a black-and-white montageof a young French officer in the pro-Nazi Vichy militia signaling a firingsquad to execute seven Jews.

More than four decades later, having been sheltered by theCatholic Church in the meantime, the officer, Pierre Brossard, is on the runafter a reluctant French government finally charges him with crimes againsthumanity.

The film, shot in France with a first-rate British cast, isa satisfying political thriller, combining a tour of scenic cathedrals andmonasteries with an examination of the murky intersection where religion,politics, guilt and self-preservation meet.

Primarily responsible for the suspense and intensity of “TheStatement,” as well as some of its shortcomings, are three masters of theircrafts. They are director Norman Jewison and actor Michael Caine — bothYiddish-speaking Protestants — who talked about the film and their personalbackgrounds in face-to-face interviews at a Los Angeles hotel.

The third is Roland Harwood, the South African-born Jewishscreenwriter, who received an Oscar for “The Pianist.”

As the hunted Brossard, the 70-year-old Caine is a devoutCatholic, whose twin goals are to escape his pursuers and to receive thechurch’s absolution, so he may die in a state of grace.

After him are two gunmen, who initially appear to be membersof a Jewish vigilante organization. They have been ordered to kill Brossard andto leave a statement on his body explaining that the assassination was inrevenge for the killing of the seven, and of the other 77,000 French Jews whodied at the hands of the German and Vichy regimes.

In the background, however, lurk powerful, shadowy figures,who have easily managed the transition from Nazi collaborators during World WarII to high-ranking officials in the postwar French governments.

The film is adapted from a roman a clef of the same title bythe late Catholic novelist Brian Moore, who based his characters on two of the Vichyregime’s more despicable figures.

Bossard is modeled on Paul Touvier, who was actuallypardoned by French President Georges Pompidou, but ultimately became the onlyFrenchman convicted of crimes against humanity.

Pulling the strings is a character known only as the “OldMan” in the film, representing Maurice Papon, who distinguished himself duringthe war by interning and deporting French Jews. He smoothly transitioned afterthe liberation to a banker and supporter of President Francois Mitterand, wasdecorated with the Legion of Honor in 1948, and then rose to police prefect of Paris.

The cast includes some top-notch British talent, among themTilda Swinton and Jeremy Northam as government officials who crack theconspiracy, Alan Bates and Charlotte Rampling. They all do their professionproud, but the film is not entirely satisfying.

Surprising for someone of Harwood’s caliber, parts of thedialogue sound stilted, especially in some of the pseudo-gangster talk. Onealso wonders how the shaky, winded and elderly Brossard repeatedly gets thedrop on young professional killers.

More serious, especially in a film billed as a psychologicalthriller, is the lack of insight into the motivations of Brossard, or, as faras that goes, of the Vichy collaborators generally. Did they hate Jews? Didthey consider themselves patriots? Were they ambitious opportunists?

The film is fully justified in indicting the shameful recordof France’s postwar governments, which, until quite recently, pulled a blanketof silence over their country’s anti-Semitism and bootlicking of the Naziconquerors during the war.

Interviews with Jewison and Caine did not resolvereservations about the film, but yielded some interesting items about two movieveterans who grew up as Christian lads in Jewish neighborhoods and are oftentaken as members of the tribe.

Jewison, 77, grew up in a working-class district in the eastend of Toronto, an area with large Jewish and Irish Protestant populations, andattended a Jewish school.

By virtue of his last name, young Norman was often tauntedby the Irish kids as “Jew boy” and “Jewie,” and identified so closely with hisJewish classmates that he asked his parents why they didn’t observe the Jewishholidays.

When his hit film, “Fiddler on the Roof,” premiered in Jerusalem,Jewison was seated next to then-Prime Minister Golda Meir. “Everybody naturallyassumed that I was Jewish and Golda kept calling me ‘boyckik,'” he recalled.

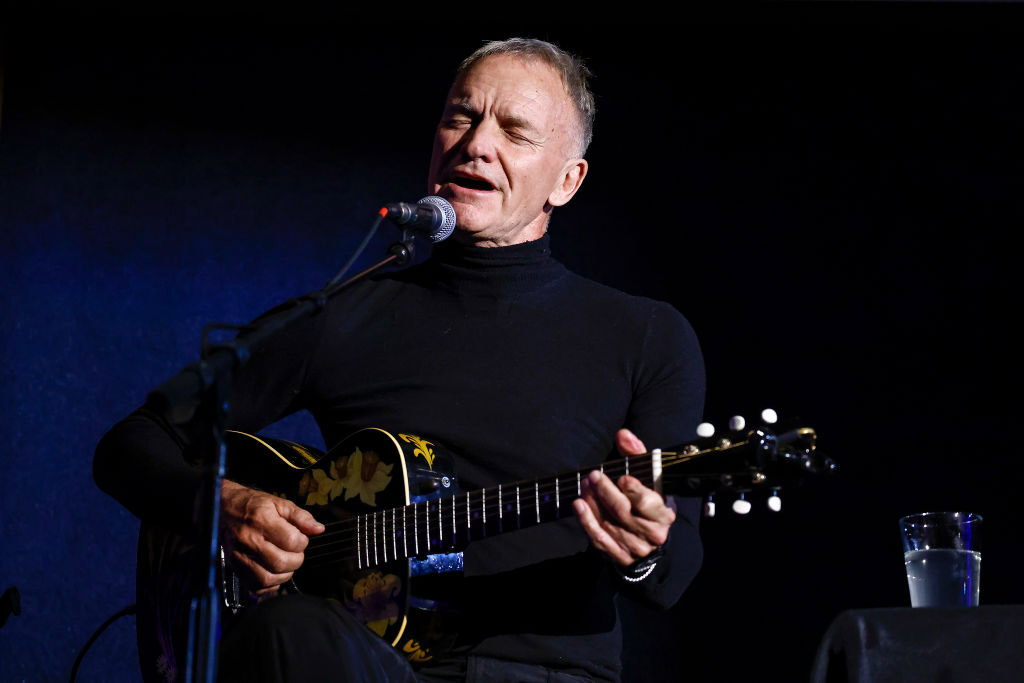

Caine — Sir Michael Caine — has made some 90 films over a 50-yearspan, but nowadays he only accepts a role if it’s amusing — such as AustinPowers’ father — or challenging.

“I decided to play the French Nazi Brossard because hischaracter was the farthest removed from my own,” he said. “I don’t want anyoneto sympathize with Brossard, but I play him as a pathetic and sad man. I havetalked to many racists and I always come away feeling how pathetic they are.”

Born Maurice Micklewhite, Caine grew up in the heavilyJewish London East End, where his cockney father was a fish market porter andhis mother a cleaning woman.

The future actor also attended a Jewish school, where aclassmate was future playwright Harold Pinter, and functioned as a Shabbos goyfor his Jewish neighbors.

“I went to their homes and lit the fires and earned asixpence,” he reminisced. “That was a lot of money to me then.”

The Yiddish he picked up in his youth came in handy whenCaine started making movies in Hollywood and his facility with the language ledto considerable speculation that he was at least partially Jewish.

Based of his knowledge of different races and religions,Caine said, “If I am struck by one thing, it is how alike all people are.”

“The Statement” is currently playing at The Grove Stadium 14(323) 692-0829 and Landmark’s Westside Pavilion (310) 281-8223. On Dec. 26, thefilm will also open in Encino, Pasadena and Irvine. Â