“The Earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep, and the spirit of God was hovering over the face of the Waters.”

Nine Los Angeles-based artists were invited to “wrestle with our current moment of de–creation, daring to hope for the possibility of new creation on the other side – just as the Spirit of God was hovering over the deep before God spoke light into the darkness.”

“Formless and Void,” at the Upside Down gallery in Westwood through Dec. 20, brings “Jews and Christians together to examine how our shared tradition provides the generative basis for creating art that heals post-Oct. 7.”

This Torah-inspired exhibit reveals the indomitable spirit of the Jewish people. All the paintings express aspects of void, formlessness and the darkness contained in them. All, without exception, found the way out of it, not by bypassing it but by facing it and moving through it.

The first to catch my attention was Galeet Gia Zeituny’s spectacular painting. In a free-flowing, colorful, seemingly abstract work, she expresses in pure instinct the mixture of feelings the Jewish People are experiencing after the Oct. 7 massacre.

The dark colors representing chaos are mixed with the colors of life and vitality in magnificent turquoise and cobalt blues and lively orange surging flames representing spiritual light. Searching narrative in her own abstract, Galeet showed me the hidden faces representing the void, despair, and darkness brought by collective catastrophe. But streams of black paint and spots of muddy colors of darkness and pain intermingle with sparkling colors of hope and life and subtle happy faces. On one side of the painting, a stream of gold paint represents what Galeet named “the hopeful future, and elevated spirituality symbolized by the richness and preciousness of gold.”

Carefully hidden, yet obvious once you see it, is the map of Israel in the middle of the canvas, highlighted by thicker coats of paint on its borders.

Ronen Pollak’s “The Light Source Within the Formless and Void” is an interesting contrast to Galeet’s painting. It is a very disciplined effort, tightly painted, very guided and nuanced, with several streams of different colors representing different feelings. While I interpreted the blackish stream to represent the dark, the red to represent blood, the other three streams to represent life difficulties or life intricacies, and the light color to represent life itself, my conversation with Ronen was a surprise.

He talked about something similar and yet very different. For him, the painting represented chaos before the creation and before the war.

“I am an optimist,” he told me. “I see that the potential is in the dark. The dark is everywhere. It is in the womb, in the brain, and in the universe.”

In the stream that I interpreted as representing life, Ronen mentioned his use of white as the light showing hope, “like the Shabbat candle.” But for him, red is the color of wisdom.

“We have the dark in the world, the evil in the world, the balagan. But it’s still in harmony, even in chaos,” Ronen mused. “God created heaven and Earth, and in the Earth was chaos. It was put in from the beginning, from the first nanosecond of chaos and the last nanosecond of creation.” It is inevitable.

Lilia Aviv Silberling’s “Organizing Dissonance” was exactly that. I loved her painting of an arm raised behind a black prison-like trellis. It evokes a cry for help from the infernal jail, but with an arm and a hand and a gracious gesture painted with lively colors of healthy flesh, reaching out for freedom and life toward the light at the top of the canvas.

Dara Feller’s “Vessel” is an intriguing photograph collage. It clearly represents the body but with mystery. Dara told The Journal about “the void, the obscure, the unknown.”

“I wanted to create something unknown from something known,” she said.

“In a world hyper-focused on Israel and its government, people forgot the singularity, the autonomy and the ownership of the body of the individual,” she said. “These are real people.”

Her collage is made up of pictures of disparate parts of her body, photoshopped under a single light source, like the sun. The collage represents part of her legs, her elbow, a line of her rib cage, and a strange angle of her lips, assembled in a nonrecognizable form. The whole montage rests on a mass representing her hair. There is one shape she could not identify. Her photograph also focuses on light and dark, form and formlessness.

Toby Levi’s “Day 1-3” is about movement — a movement that goes in two directions, toward the light and emanating from the light.

“I usually use narrative in my work. However, I was asked to make an abstract related to the exhibit’s theme. The first day of creation represented light. The second and third day, water, and the forms being created.”

A fascinating detail: Toby decided to listen to the whole Torah while he was working on his painting — a yellow dot at the center, with cobalt blue circles painted over a light blue background, with over a hundred different shapes representing what was created in the universe.

His hundred different shapes seem to move toward or from the center point. They are all composed of the same red and orange, with some black lines, over a cobalt blue background, as if unconsciously made from “the same God particle,” the atom of the universe. He also was able to express a dual movement with the shapes — both as emerging from the center and flying out to the universe and coming from the universe toward the center. It is a fascinating movement, in and out at the same time.

The canvas seemed too small for such a large concept — a very big concept squeezed into a small space. Toby confirmed that he also wanted a much larger canvas but was asked to keep the painting size within a specific framework.

Julia Elihu’s “The Shape of the Shadows” is a video showing a big couch and a woman sitting on the floor with her head resting on the edge of the couch.

For Julia, her video represented shadows of winds, windows, birds, and lights, as well as the joy, brightness, and light to which we are addicted. But she also wanted to explore “the idea of darkness, as darkness shapes life itself. Light itself is formless.”

Julia talked about the need to process darkness and the understanding that she’s not stuck in it. At 27, this young artist was thankfully encountering real darkness for the first time in her life. It made her question the meaning of life and search to find the understanding of death.

She expressed how “It takes a movement from extreme sadness and darkness to get to life.” Her message was that we have to pass through the darkness but not get lost in it. “The light within us remains our guide.”

There are other paintings in the exhibit that were also worth seeing.

All the paintings reflect rebirth while confronting the darkness, pain and suffering, expressing the spirit of Israel and the Jews.

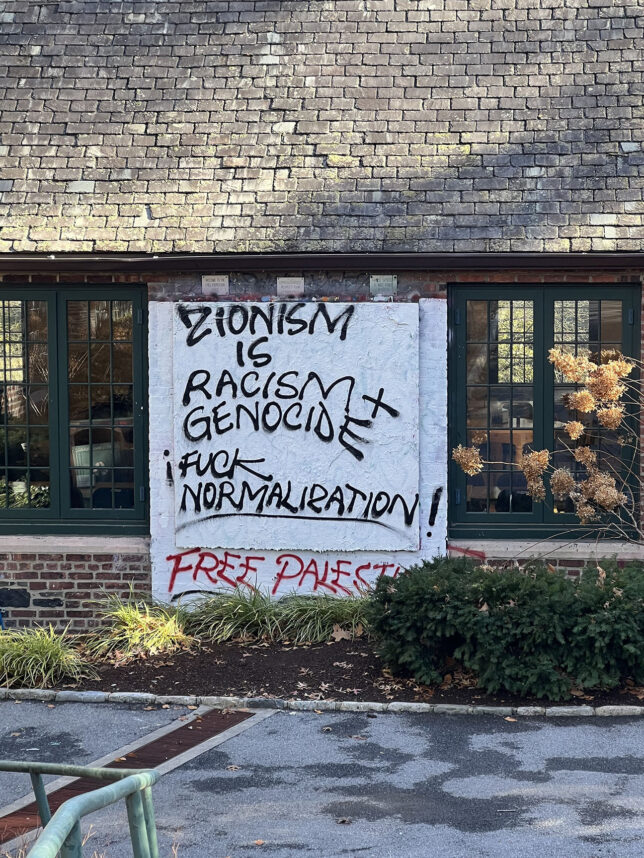

After such an immense tragedy that re-awakened the collective trauma of both the Holocaust and the 2000-year-old worldwide antisemitism, all the paintings reflect rebirth while confronting the darkness, pain and suffering, expressing the spirit of Israel and the Jews. They all represent the vision of life and hope. It reminded me of the early 1970s when I was looking at German and other European art after World War II. I remember being struck by how incredibly dark, tortured, hopeless and lifeless it was. That might have been a clue as to where Europe would go in terms of its own spiritual survival. I was relieved and again grateful that the Torah gave us such a resilient capacity for healing and renewal. As I like to say, hope is the middle name of the Jewish People. Hope and resilience are in our DNA.

Gina Ross, MFCT, is the Founder/President of the International Trauma-Healing Institute USA (ITI-Israel).