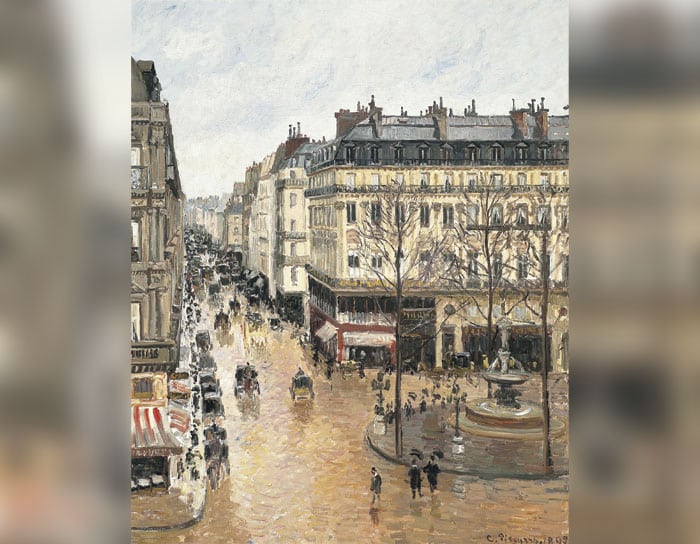

Camillie Pissarro’s “Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain.”

Camillie Pissarro’s “Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain.” A three-judge panel of a California court ruled on Jan. 9 against a family’s appeal to retrieve a Nazi-looted artwork that currently hangs on public display in a Spain museum.

“Cassirer v. Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation,” overseen by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, was concerned with artist Camille Pissarro’s 1897 Paris streetscape, “Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain.” During World War II, the painting, considered a masterpiece of French-impressionism, belonged to Lilly Cassirer, a Jewish woman living in Germany. Lilly was forced to surrender the painting to the Nazis in exchange for an exit visa in 1939.

For decades, the painting moved between different galleries and owners before being sold to the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum in Madrid, Spain. And for the past 24 years, the Cassirer family has been trying to get back the painting from the national museum in Spain.

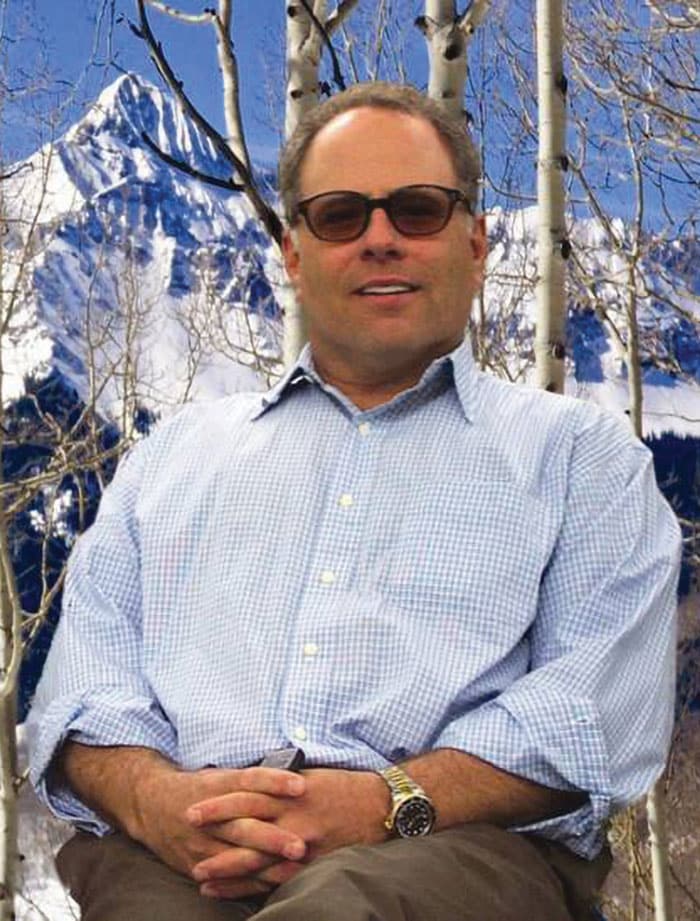

Courtesy of David Cassirer

David Cassirer, Lilly’s great-grandson and one of three plaintiffs in the case, denounced the court’s ruling that the painting remain in Spain.

“I was certainly stunned and hurt by their decision,” Cassirer told the Journal in a phone interview from his home in Telluride, Colorado. “In a perfect world we would have gotten this painting back 20 years ago. This was a serious miscarriage of justice.”

“We were all just sickened by the ruling,” he continued. “We’re upset, amazed and hurt. On behalf of my immediate family, all of whom have died; on behalf of the Jewish people, facing exponentially growing antisemitism, this is a terrible ruling.”

The high-profile case has navigated through various courts since Claude Cassirer (David Cassirer’s late father and Lilly’s grandson) learned of the painting’s existence in 2000 and petitioned the museum, as well as the Spanish government, for its return. That petition was denied. Last week, the Cassirer family faced its latest setback when an appellate court, in a highly technical decision, determined Spanish law, not California law, applied to the case, meaning the museum had acquired the painting through adverse possession.

The court ruled that because the museum, which acquired the painting in 1993, had held the painting for a minimum of six years before the Cassirer family petition made a claim for it, Spanish law dictates the museum has fair possession of it. And because the Ninth Circuit court determined to go by Spanish law, not California law, the painting will remain with the museum for now.

Long at issue has been whether the museum was knowingly acquiring stolen artwork when it purchased the Pissarro painting, along with other works, from Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, an industrialist and art collector, in 1993. The museum’s leadership maintains it did not know, while Cassirer’s legal team has argued any knowledgeable art collector would have known the work was stolen.

Before learning of the painting’s existence, the Cassirer family had presumed the painting lost or destroyed; in 1958, Lilly was granted a settlement for the presumed-lost painting from the German government.

Before learning of the painting’s existence, the Cassirer family had presumed the painting lost or destroyed; in 1958, Lilly was granted a settlement for the presumed-lost painting from the German government.

Not at dispute is that the impressionist masterwork, which could be worth up to $60 million, was once the property of Lilly Cassirer.

“There is no dispute that the Nazis stole the Painting from Lilly,” Judge Carlos Bea, one of the three circuit judges to hear the appeal, wrote in his opinion.

In a dissenting opinion, Circuit Judge Consuelo Callahan wrote that she agreed with the court’s decision from a legal standpoint but was troubled by it.

Spain, Callahan wrote, “should have voluntarily relinquished the painting.”

Cassirer was joined by the estate of his late sister, Ava, and United Jewish Federation of San Diego, as plaintiffs. Cassirer’s father, Claude, was active with the Jewish Federation of San Diego and left a percentage of the painting’s proceeds to the Federation.

One of the family’s attorneys, Sam Dubbin, a principal in the law firm Dubbin and Kravetz and an expert in the restitution of assets looted from Holocaust victims, said the family planned to appeal for an en banc review, a special procedure when all judges of a particular court hear a case.

“We believe the decision is incorrect in its application of California’s choice of law framework, and Mr. Cassirer will definitely seek en banc review,” the legal team said in a statement.

Cassirer, the only living direct descendant of Lilly, still believes his family will get the painting. He hopes to sell the artwork at auction and would use the proceeds to start a family foundation. It’s what his late father and mother—the two died, respectively, in 2010 and 2020—would have wanted.

“They were ecumenical. They would be proud if I were helping Black people, Native Americans,” he said. “That’s how they raised me.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.