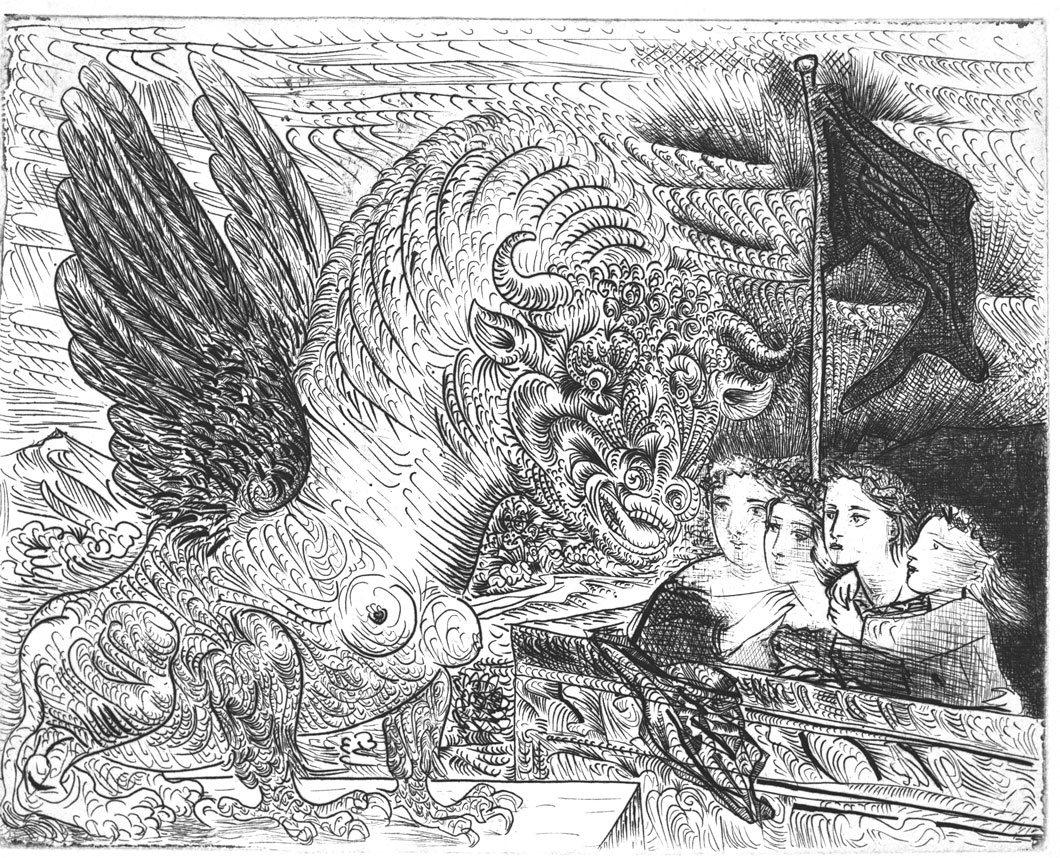

Fred Grunwald’s collection included Pablo Picasso’s “Winged Bull Watched by Four Children.” Photos courtesy of Hammer Museum

Fred Grunwald’s collection included Pablo Picasso’s “Winged Bull Watched by Four Children.” Photos courtesy of Hammer Museum On an early May morning in the mid-1930s, Gestapo officials barged into Fred Grunwald’s apartment building near Düsseldorf, demanding of the landlady, “Where is the Jew?”

Once inside the businessman’s home, the officers declared that because he was a leader of the local B’nai B’rith lodge, they would search his apartment and arrest him. They promptly tore apart the master bedroom, in the process seizing eight to 10 portfolios of Grunwald’s treasured collection of print artworks from an antique cabinet.

When Grunwald returned home after his arrest, he found that about 500 of his prints had been taken, including works by two of the most renowned German expressionists, Edvard Munch and Ernst Ludwig Kirschner. (The prints were never returned.)

Grunwald, who died in 1964, went on to amass an even more impressive collection after immigrating in 1939 to the United States, where he became a successful clothing manufacturer.

Pieces donated from his world-class collection in 1956 established what is now the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts at UCLA, currently housed at the Hammer Museum in Westwood. Now, information about the Grunwald family and a digital archive of their collection are available on a website created by the museum, “Loss and Restitution: The Story of the Grunwald Family Collection,” which went online last month.

“It’s important for research for art historians, curators, people interested in the history of early Los Angeles collections, the history of the Holocaust and Germany, and the emigres who came from that country,” said Cynthia Burlingham, director of UCLA’s Grunwald Center.

The archive, one of several digital initiatives to be funded with the help of a $500,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, includes in-depth essays about Grunwald, official documents and some 1,500 images from his collection at UCLA. Many of the images are of 19th and 20th century French, German and American prints, as well as Japanese woodblock prints.

Erich Heckel’s “The Dead Woman” (1912), for instance, depicts a deceased, half-naked woman in bed, as two men mourn her in the foreground, all rendered in stark black and white. Woodcuts by another German artist, Gabriele Münter, mostly from around the turn of the 20th century, feature cityscapes and domestic scenes somewhat less raw than works by her fellow expressionists. There are pieces by Marc Chagall, Max Ernst and Pablo Picasso, whose “Winged Bull Watched by Four Children” (1934) centers on a swirling image of a winged bovine.

“Grunwald collected very intelligently,” Burlingham said. “He looked at very interesting artists who did excellent work; he bought good examples of their work that were in excellent condition. He also looked at the best artists — Picasso, for example — even though in some of his notes he bemoans the fact that he couldn’t collect certain Picassos because they were too expensive.”

Grunwald further became one of a group of émigré collectors who helped nurture the budding arts scene in Los Angeles decades ago.

The archive, in part, seeks to answer the question, “Who was Fred Grunwald?” said Philip Leers, the Hammer’s project manager for digital initiatives.

According to an essay by the collector’s son, Ernest Grunwald, who died in 2002, his father was born into a middle-class family in Dusseldorf. As a young man, he was drafted into the German army and, while fighting in World War I, shattered the bones in his left leg. During a two-year hospital convalescence, when his limb was amputated at the knee, Grunwald developed an avid interest in German graphic art, “which eloquently expressed the bitter anger of the artists after the First World War,” Ernest Grunwald wrote.

According to another account, Grunwald began collecting prints almost immediately after he was discharged from the hospital — initially, works by German artists such as painter, printmaker and sculptor Käthe Kollwitz, and the Jewish printmaker and painter Max Liebermann. The archive presents Kollwitz’s 1924 work “Germany’s Children Are Starving,” in which plaintive children appear to beg for food, holding up empty bowls.

In 1930, the senior Grunwald established his own shirt-collar business, which did well during the early Nazi period. But after his home was raided about five years later, he realized the Third Reich had become too dangerous for Jews. In August 1938, he hid jewelry inside moving boxes as the family anxiously awaited visas to immigrate to the United States.

Grunwald was arrested three months later, on the day after Kristallnacht, the anti-Jewish attack that signaled the start of the Holocaust. It was only through the intervention of a Gestapo officer who noticed Grunwald’s war injury that the businessman was released. After a former employee unsuccessfully attempted to blackmail him, Grunwald, his wife and two children boarded a boat for the United States.

His post-war collecting was “systematic and voracious,” according to an archive essay by scholar and archive lead researcher Leslie Cozzi. During the late 1950s, Grunwald filed restitution claims with the German government and eventually was awarded 125,000 German marks (about $75,000 today) for the theft of his pre-war art collection.

Grunwald spent his restitution money on acquiring even more works by both foreign and local artists.

“He’s part of a wider 20th-century circle of cultured individuals who really are responsible for many of the major cultural institutions in this city,” Burlingham said.

Visit the Grunwald digital archive at hammer.ucla.edu.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.