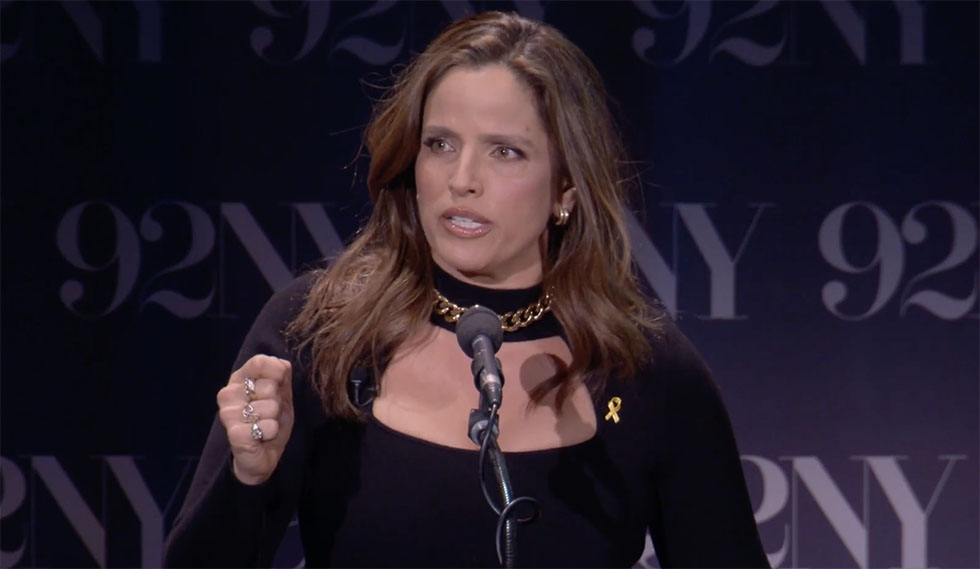

In the days following Shabbat HaShachor — the black Saturday of October 7th, on which Hamas perpetrated horrific, barbaric atrocities against Israelis — we asked our community at Valley Beth Shalom for names of loved ones who had been murdered, kidnapped, or called up for military service to defend the future of the Jewish people. I offered to read all of the names at each Shabbat service to add a human face to the war. In just several days, we collected well over 100 names. This war is not a case of six degrees of separation. This war feels very personal. Everyone I know has been affected by the savage Hamas attacks.

Not a day goes by when an Israeli family doesn’t enter our synagogue in tears, wanting to know when and where they can say Mourner’s Kaddish. For the victims of murder, we’re familiar with the ritual of Kaddish. Many of us are mourning. For soldiers in the IDF, we have all participated in raising money and gathering resources that they desperately need. For the kidnapped, how can we respond? What does the Jewish tradition say? We need to know because our entire family is being held hostage.

Our close friends, Jon and Rachel Goldberg-Polin, had not heard back from their son Hersh. Hersh was at the music festival. He had been kidnapped and is being held captive in Gaza.

The news of the war began for me when my cell phone buzzed me awake on Shabbat Simchat Torah. While I don’t normally answer my phone on Shabbat, there was something unusual about all of our phones ringing at once. The awful videos began to rush in: Bloodthirsty murder, girls being kidnapped by men on motorcycles, a half-naked young woman paraded through Gaza on the back of a pickup truck. Then, the horror came closer. Our close friends, Jon and Rachel Goldberg-Polin, had not heard back from their son Hersh. Hersh was at the music festival. He had been kidnapped and is being held captive in Gaza. His story has been told in the pages of The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, and Rolling Stone.

At approximately 8 a.m., Jon and Rachel received a text from their 23-year-old Hersh that read “I love you” and “I am sorry.” They have not heard anything since. As Rachel expressed in a recent interview, “I am living every mother’s worst nightmare.” Photos have surfaced that show Hersh huddled in a bomb shelter with other youngsters, trying to defend themselves until Hamas kidnapped all but eight of them. A survivor of the music festival informed Jon and Rachel that their son had lost part of his arm amidst the Hamas butchery, according to The Los Angeles Times. He needs immediate medical attention.

We love Hersh. When we lived in Jerusalem, our families spent Shabbatot together. Hersh and his two sisters were approximately 10 years older than our kids and they used to play together on Shabbat. Our kids loved them. They still do. I can still see 12-year-old Hersh patiently playing with my 2-year-old son on the carpet. Hersh loves basketball, and he liked to tell me about the crazy Jerusalem HaPoel games. He enjoyed music and having fun. Hersh Goldberg-Polin is our collective son.

The story has sparked a global movement. American media has published Hersh’s story. Banners can be seen in soccer games in Germany reading “Bring Hersh Home.” I encourage you to like and share his pages on social media. We must bring Hersh home.

Unfortunately, Hersh is not the only captive to whom we feel connected. Our friend, Rona Passman, has an elderly aunt and uncle who have been kidnapped as well. Hamas kidnapped Amiram and Nurit Cooper from their home in Kibbutz Nir Oz. Hamas attacked the kibbutz, burned down houses, and massacred and kidnapped families. Haaretz has reported that between a quarter and a third of the kibbutz’s 350 families have been killed or kidnapped. After raising their flag over the kibbutz, Hamas kidnapped 84-year-old Amiram and 79-year-old Nurit among the captives. Thank goodness, Nurit was released on October 23, along with another hostage. She was part of the 4 released hostages so far. Yet, Amiram remains in captivity. Amiram is our collective uncle. We must bring Amiram home.There are countless stories of the approximately 222 Israelis being held hostage in Gaza. Shira Albag is beginning a media campaign about her 18-year-old daughter, Liri, who is among the kidnapped. Others are beginning personal campaigns as well. We must bring Liri home. We must bring them all home.

President Biden hosted a Zoom meeting for all of the families of American citizens. Jon and Rachel attended the meeting. The parents pleaded for any news concerning their children in captivity. The parents pleaded for medical attention for all of the hostages. At this point, there are no answers. In this world of pain and peril, how do we move forward from here? What does our tradition say?

The Jewish tradition of Pidyon Shvuyim (redeeming captives) is long and complicated … Halakha, or Jewish law, views the redemption of captives as a higher priority than building a synagogue, even after the funds have been raised.

The Jewish tradition of Pidyon Shvuyim (redeeming captives) is long and complicated. Beginning in Leviticus 19:16, part of a section of scripture that academics deem as the Holiness Code, the Torah instructs us “Do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor …” Based on this verse, Rashi explains that we must rescue one another from death. Maimonides codified these positions by stating that even if a Jewish community raises money to build a synagogue, they may use it instead to redeem those held as captives (Mattenat Aniyyim 8:11). Halakha, Jewish law, views the redemption of captives as a higher priority than building a synagogue, even after the funds have been raised.

The opinions of our rabbis stem from our Babylonian Talmud, which calls the redemption of captives “a great mitzvah” (Bava Batra 8b). The discussion of this concept appears throughout many tractates of the Talmud. There is a tension in another section that introduces the concern for paying too great a price for the return of a captive (Gittin 45a). The dilemma is whether a hefty price will encourage the kidnap of additional hostages. We saw this concern play out when Gilad Schalit was redeemed in 2011 after five years of captivity. In exchange for his release, more than 1,000 Hamas prisoners were released, including the evil mastermind behind the October 7th Hamas assault. How do we redeem Jewish captives without encouraging the kidnapping of more Jewish captives?

If Schalit’s exchange for 1000 terrorists directly invited Hamas’s brazen assault on humanity, we must now bring these 222 back in a way that does not encourage another similar round.

If Schalit’s exchange for 1000 terrorists directly invited Hamas’s brazen assault on humanity, we must now bring these 222 back in a way that does not encourage another similar round.

I have spent much time considering my halakhic obligation since I found out about Hersh. We must redeem the 222 Israeli hostages as quickly as possible. Our tradition mandates it. At the same time, if Schalit’s exchange for 1000 terrorists directly invited Hamas’s brazen assault on humanity, we must now bring these 222 back in a way that does not encourage another similar round.

We must find examples of freeing hostages from which we can learn. There are two positive case studies for redeeming the hostages without a demoralizing diplomatic exchange of thousands of terrorists for innocents.

The first way to reframe the conversation can be seen by examining the raid on Entebbe … That public display of force proved itself to be an effective deterrent for decades.

The first way to reframe the conversation can be seen by examining the raid on Entebbe. On July 4, 1976, two Palestinians and two Germans hijacked a plane of 248 passengers and diverted the plane to an airport in Uganda. Over two days, the world negotiated the release of citizens of different countries. 148 non-Israeli passengers were released, while the terrorists held onto 94 remaining passengers, most of whom were Israeli. It is worth noting that the 12 member Air France airline crew remained, refusing to leave the Israelis behind.

In a military rescue operation only imaginable by Hollywood action filmmakers, commandos from the IDF Special Forces arrived and rescued practically all of the hostages. The leader of the operation, Commander Yonatan Netanyahu, was tragically killed toward the conclusion of the mission. This mission laid before the world a new policy of the Jewish people toward captives: We will rescue Jews no matter the challenge, and we will make the perpetrators pay for their crime. That public display of force proved itself to be an effective deterrent for decades.

Entebbe stood as a reaction to the failure of the Munich Olympics in 1972 where Israel trusted others to save Jews from terrorists. After the bloody massacre of Jews perpetrated by those Palestinian terrorists in 1972, we had to change our approach in rescuing Jewish captives. We stand today in a moment of shifting historical tides once again.

To learn from the Entebbe precedent is to assume that the IDF is quietly preparing, mapping clues, and strategizing for rescue missions. While this kind of response would certainly prove to build the public morale, as I’m not a military expert, I can offer little insight. I want to believe that Israel can pull it off. I want to believe that we, as a people, still possess a courageous Yonatan amongst us.

The second way to reframe the redemption of Jewish hostages utilizing a positive case study is to examine our effort to free Soviet Jewry. Rather than clandestine diplomatic negotiations, throughout the 1980’s, the entire American Jewish community publicly and tirelessly fought to free Soviet Jewry. That campaign reflected a marathon effort that unfolded over years and years. A leader of that movement from our own VBS community, Ed Robin (z”l) helped inspire and mobilize Jews from across the country to gather publicly in Washington DC and demand global pressure at a particular inflection point.

On Freedom Sunday, December 7, 1987, American Jewish leaders gathered 250,000 on the National Mall in Washington DC to force public pressure on the Soviet Union to allow Soviet Jews to emigrate. In his own words, Robin wrote in The Jewish Journal on December 5, 2007, “The Soviet Jewry movement was proof positive that a group of determined people has the power to force a compelling moral issue front and center on the agendas of the United States and the entire world. Freedom Sunday in many ways marked the culmination of the most successful mass advocacy effort ever undertaken by American Jews.” It is time for successful mass advocacy once again.

It is our collective responsibility to apply pressure to our governments and all governments that the hostages must be freed. To allow Hersh, or Nurit, or Amiram, or Liri to sit in Gaza for another day is a tragedy for us all.

It is not for the Israeli government alone to negotiate for the 222 hostages. It is definitely not for the American government to negotiate for the release of American citizens alone, and leave the Israelis in captivity. It is our collective responsibility to apply pressure to our governments and all governments that the hostages must be freed. To allow Hersh, or Nurit, or Amiram, or Liri to sit in Gaza for another day is a tragedy for us all.

Isolated protests have arisen throughout the world such as the Israeli American Council’s “Bring Them Home Now” rally in New York October 19. Graffiti bearing slogans such as “Bring Hersh Home” have been spray painted in Barcelona. There is no unifying movement to free the hostages. When I was growing up, a large sign was in front of every American synagogue that read “Save Soviet Jewry.” It reinforced a value that we’re all family and our entire family deserves to be free.

As American Jews, it is now incumbent on us to hang banners from all of our synagogues that read clearly: “Bring Them Home/We Stand in Solidarity with Israel.” Valley Beth Shalom has produced the graphics and made it available for other synagogues across our city and across the country to use. Valley Beth Shalom will hang our banner in the most public manner so that everyone can be reminded each day of the value of Pidyon Shvuyim, redeeming the hostages. We must bring them all home.

35 years after Freedom Sunday, can American Jewish leaders mobilize and stand together behind this cause? Can the American Jewish community once again muster the kind of public mass advocacy that can bring global pressure onto Hamas, the Palestinian Authority, and the larger Arab world? Turkey, Egypt, and Qatar have all publicly acknowledged the possibility of playing some role in negotiating the release of the hostages. The United States government should apply pressure to all foreign governments who maintain relations with Hamas until the hostages are freed. I don’t hear any American Jewish leaders raising awareness for the hostages. Their freedom is our moral and halakhic obligation.

As Jews, we must redeem the hostages. The freedom-loving world should insist that the hostages be freed because the act of kidnapping people and holding them for ransom is barbaric and intolerable. Why aren’t we shouting about the hostages? We must sustain the level of pain and anguish that we felt on October 7th. I guarantee the families of the kidnapped have not yet numbed to the pain. We cannot desensitize either.

Israel is fighting a war that will most likely increase in fronts, in complexity, and in severity. It maintains the weaponry to win the war. How quickly Israel wins, how many IDF soldiers are exposed, and how much devastation for local civilian populations in Gaza, in Lebanon, and possibly in Syria are questions for Israel to decide. Many American Jews have stepped up to support the war effort. Israel must win decisively, but we will not decide the war. In this moment, we can help Israel in four ways: First, donating money to help organizations and even helping the IDF secure resources; second, calling our elected officials and advocating for them to support Israel through legislation and public statements; third, traveling to Israel and volunteering while soldiers are away fighting (I suggest reviewing Nefesh B’Nefesh’s volunteer list: nbn.org.il/life-in-israel/education/higher-education/volunteer-programs); and fourth, publicly advocating for the release of the hostages.

In many ways, the fourth goal is challenging. To publicly advocate for Israel and the release of the hostages takes a toll on us emotionally and physically. There is no assurance that anybody is listening or that they will be freed. It is too easy to forget about their plight because, after all, the hostages and their families are distant. It is human nature to favor what we see and what is near. Yet, Judaism often encourages us to consider the exact opposite. I encourage you to remember Hersh, Nurit, Amiram, and Liri.

Judaism calls us to consider ideas beyond our immediate grasp such as God, relationship, community, and Israel. We train ourselves to care about these values through routine ritual. We cover our eyes to say the Shema or to light the Shabbat candles. We come together for Shabbat dinner or celebrations or in mourning. We train our behavior through reminders and practice.

We must also develop communal and personal reminders of the hostages. Although “Kidnapped” signs have appeared throughout Boston and other cities around the world, I have not seen any signage on display yet at our synagogues. Last Shabbat at Valley Beth Shalom, we covered one of the seats on our bimah with the Israeli flag, recognizing that we have members of our family who are missing. Looking at our bimah, one immediately recognizes that something is wrong. We recite the prayer for Pidyon Shvuyim, redeeming the hostages, each Shabbat.

Last Shabbat at home, we lit an extra candle for Hersh. And after reciting the blessing over the candles, we said aloud, “We miss you Hersh and we hope you come home soon.” Our children wished for Hersh’s safe return as well. Prayer is the act of saying out loud the things that matter. The hostages matter.

I went to sleep last week, and I dreamt that Hersh returned home. I dreamt that Jon called and asked me to have his son stay with us in L.A. for a while. I imagined Hersh and I walking together to Valley Beth Shalom on Shabbat. I envisioned him sitting at center court and cheering on the Lakers. I felt him having dinner with our family, laughing and acting silly again.

It was a Shabbat dream. It was a taste of the world as it will be one day. We must bring Hersh home. We must bring them all home. We must walk through the streets and scream in pain. We must hang banners from our synagogues. We must shake the pillars of power with mass advocacy. We must ritualize our remembrance of them. So that when they’re freed and we bring Hersh to Valley Beth Shalom, we can all look him in the eyes and say, “I never forgot you. I worked every day to bring you home.”

Rabbi Nolan Lebovitz serves as the senior rabbi at Valley Beth Shalom in Encino, CA, and sits on the Executive Board of the Zionist Rabbinic Coalition. A Fulbright Scholar, Lebovitz spent time last year studying at Bar Ilan University in Israel. He wrote and directed two documentaries: “Roadmap Genesis” in 2015, and “Roadmap Jerusalem” in 2018.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.