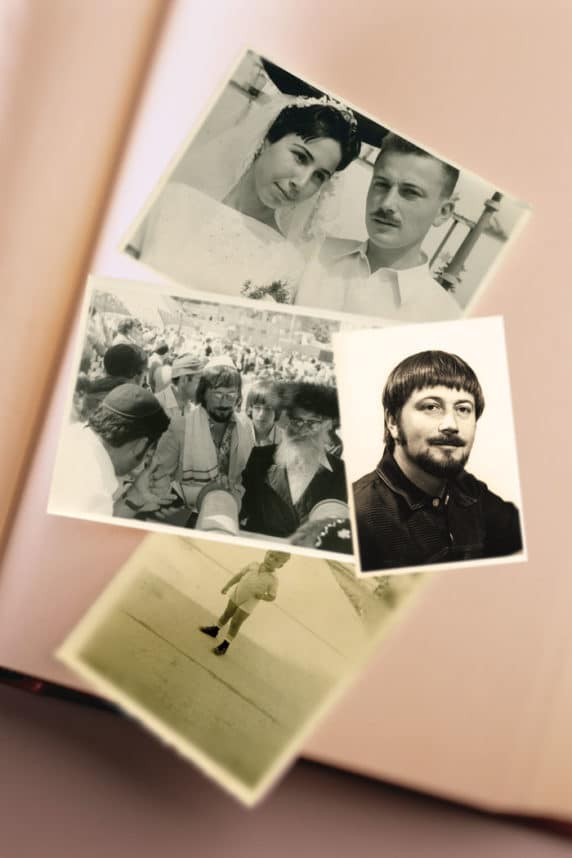

Chaim Pearl (seated) and his family, 1931.

Chaim Pearl (seated) and his family, 1931. He holds seven honorary doctorates and is the recipient of the A.M. Turing Award (called the “Nobel Prize of Computing”), but the first question I wanted to ask Dr. Judea Pearl focused on the flaws that his late wife, Ruth, z’l, found most unnerving about him.

“I never thought I had flaws,” he chuckled. But after thinking about the question for a moment, Pearl responded with his trademark wisdom, “I was born without flaws, true. But my marriage made me humble. Through Ruth, I learned that I do have a few.”

It’s easy to be in awe of Pearl. He’s been called “one of the giants in the field of artificial intelligence” by UCLA computer science professor Richard Korf. But anyone who knows him understands that Pearl is most comfortable when he can be himself, speak freely and, yes, make many jokes. His sense of humor may, in fact, constitute the least known aspect of his formidable being. That, and his unbelievable penchant for staying up late to get things done.

When our first of two interviews fell apart due to scheduling constraints, Pearl offered another time slot that ended at 5 a.m., if I “wasn’t too tired.” This only served to remind me that if, at 85, I am half as productive and at the service of the Jewish people and Israel as Pearl, I will surely host a party for myself and invite my friends and artificial intelligence (A.I.) overlords.

“I’ve psyched myself into believing I’m useful”

Artificial intelligence is almost synonymous with Pearl’s name given that it is an area of study to which he’s proved indispensable. Pearl developed a revolutionary mathematical model called the Bayesian Networks, which allows computers to deal with uncertain information, as well as a mathematical framework for causality (causal inference), allowing computers to reason with cause and effect relations. What is most extraordinary about his career is how much his research has impacted other fields of study, including philosophy, psychology, statistics, medicine and social sciences.

What is most extraordinary about his career is how much his research has impacted other fields of study, including philosophy, psychology, statistics, medicine and social sciences.

“A.I. is ourselves; it’s our souls,” he said. “We are curious about our own thinking and emotions, and A.I., by emulating these activities, helps us understand ourselves better. It has destructive potential, of course, but it’s going to help us first, before it’s abused. We have to learn to control it.”

Naturally, I wanted to know how such a prolific mind spends his days.

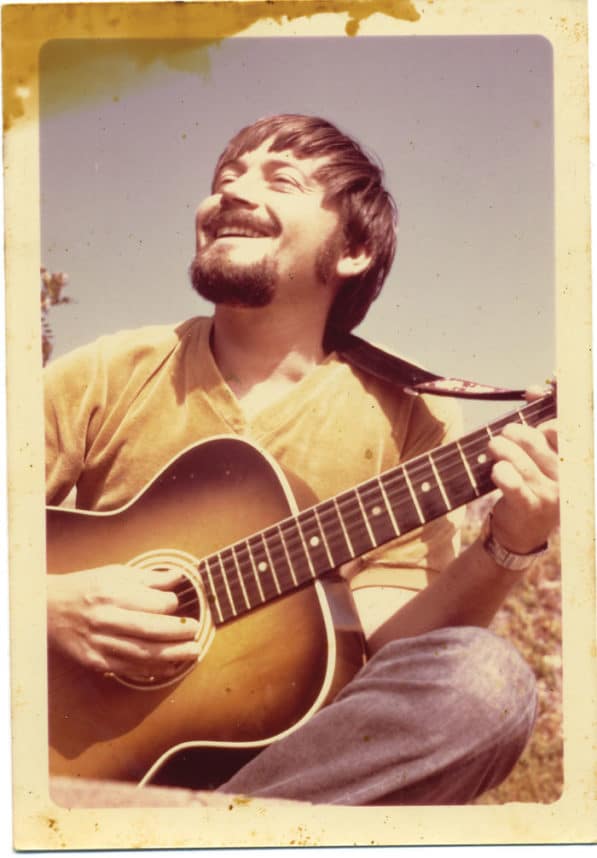

“I stay home and mostly walk from one room to another,” he quipped. That sense of humor must have elevated home life for him, Ruth, and their three children, Tamara, Daniel, and Michelle. Tragically, Daniel, a talented musician and journalist who was on assignment for The Wall Street Journal, was kidnapped and murdered by terrorists in Pakistan in 2002, motivating the couple to create The Daniel Pearl Foundation. The non-profit uses journalism, music and dialogue to promote understanding and tolerance worldwide (a network of global concerts called “Daniel Pearl World Music Days” was established in 2002 and takes place each October).

“I get up every morning with a smile on my face because there are so many things to do and I’ve psyched myself into believing I’m useful.” — Judea Pearl

True to form, beneath Pearl’s humor resides an element of emet (truth) and humble acceptance of reality: “It’s very strange for me to walk from room to room and not find Ruth there,” he admitted. “Finding the rooms empty is a new experience which I’m trying to absorb.” He then added, “But, I’m not depressed; I get up every morning with a smile on my face because there are so many things to do and I’ve psyched myself into believing I’m useful.”

Ruth, for those who knew her, was a formidable woman, mother, grandmother, electrical engineer and computer software analyst. And, most will argue, she was the only match for Judea Pearl.

The two met as undergraduate students in 1956 at The Technion (Israel Institute of Technology) in Haifa. Ruth was one of just four women in a class consisting of 120 men. “I liked the way she walked; it was special,” Pearl recalled. “Everybody walked because it was safe; Ruth walked because she owned the ground on which she stepped; she was more secure than I was.”

Ruth’s confidence, Pearl believes, was a result of her childhood in Baghdad. Well-versed in what he calls “Muslim dialects,” young Ruth was tasked with running various errands for her family that forced her to hold her ground while interacting with the local Muslim community, some of whom were hostile to Jews.

“She could stand up to anyone knowing what she wanted and had no hesitation to demand what she thought she deserved,” Pearl recounted.

Of course, I wanted to know what Ruth saw in Judea.

“She kept saying, ‘The only reason I stay with you is because you’re not boring,”” Pearl described while laughing.

The Foot Soldier

Presently, Pearl is taking extra precautions against COVID-19 by mostly staying at his home in Encino, Calif. He divides his time between three endeavors that, he admits, bring him tremendous meaning: scientific research, particularly focused on A.I.; helping his family adjust to life without Ruth (she passed in July at age 85); and finding ways for students and professors to reclaim the nobleness of Zionism, especially at UCLA, where he began his teaching career in 1969 (and founded the Cognitive Systems Laboratory in 1978).

“These are three major battles,” Pearl noted, “but I’m working as a foot soldier in the trenches and making progress daily.” He feels a duty to offer emotional support to his family. When I asked Pearl who supports him, his instinctive answer was “I don’t need support.” But upon reflection, he said. “My support comes part from my daughters and grandchildren, part-resilient family legacy, and part-lifelong sabra [one who is native to Israel]: I’m as strong as our people.”

Pearl’s mentality and resilience is no surprise; born in Tel Aviv in 1936, he belongs to a generation of Jews who lived in what was formerly known as Mandatory Palestine before the modern State of Israel was established. What is surprising (and uplifting) is how Pearl responds to questions about antisemitism in his youth:

“I grew up as a sabra, which means that I was shielded from all travesties of life,” he said. “I was supposed to be the ‘new Jew,’ who is not supposed to know anything about on-going antisemitism, and who gets to live freely, with his head up high, singing ‘Maccabee Gibbor’ (‘Maccabee, My Hero’).”

Pearl’s family left Warsaw, Poland, for Israel in the 1920s. He was the first in his family to attend college (his mother, Tova, and his father, Eliezer, completed only grade school in Poland). “But the value of education was very dear to my mother,” he said. When he was in fourth grade, a teacher told his mother, “Spend everything you’ve got and give him [Judea] an education.”

Pearl is a descendent of a famous leader and rabbi known as the Kotzker Rebbe (1787–1859); his grandfather, Chaim Pearl, was a Chasidic Zionist who helped rebuild the Biblical city of Bnei Brak, where Pearl spent his entire childhood (he was born in Tel Aviv because, at the time, Bnei Brak lacked a hospital). As a child, he didn’t experience antisemitism, not even from local Muslim Arabs; instead, he and other Jewish children played alongside Arab children near the Yarkon River, unable to understand one another’s language.

“The Muslim Arab kids came with their donkeys and we shared rides in orchard groves in a village next to Bnei Brak,” he reminisced. “All of our playing and games were done without words.”

Not even ominous news about Nazism in Europe could convince a young Pearl that antisemitism continued to exist in the world. In 1941, he found his mother in tears at the kitchen table: “She informed me that her family was caught in a war in Europe. I told her that everything would be okay, wars come and go, but she responded, ‘This is a different kind of war.’” Pearl remembers his father and a large crowd, including rabbis and political leaders, rallying and speaking against Nazi atrocities in the town square, but for six-year-old Judea, “it was just an outing.”

His mother lost both parents, a brother and a sister, in the Holocaust (only one sister survived); his father lost all of his extended relatives. “Most homes in Bnei Brak had lost someone,” he recalled.

After the Holocaust, Pearl read books about the concentration camps, the camp survivors and their heroic efforts to break through the British blockade. “But these were stories,” he said. “I didn’t truly comprehend what happened there. Then, around 1946-47, refugee children started coming [to then-Mandatory Palestine].” Some of those children joined his class. “I couldn’t understand why they wouldn’t be like us [who were born in Israel],” he said. “We were different from them: They had white-skin, were mild-going, hesitant children—mostly orphans.”

The dichotomy of the sun-kissed, carefree Jewish children who were born in Israel, never having known antisemitism first hand, and those who had survived the Nazis, was not lost on him.

The dichotomy of the sun-kissed, carefree Jewish children who were born in Israel, never having known antisemitism first hand (except from history books), and those who had survived the Nazis, was not lost on him. “They behaved so differently than us,” Pearl said, recalling one incident in which the school threw a party and one of those kids burst out crying and said she missed her mother. “That really surprised us, because we [sabras] were happy to get away from our mothers, from time to time, even most of the time.”

“The New Jew”

Judea’s marriage to Ruth, which lasted 61 years, gave him an understanding of the struggles of Jews from Arab and Muslim countries. When Ruth was just six years old, she survived the 1941 Farhud in Baghdad, Iraq, in which thousands of Iraqis, soldiers and civilians alike, tore through the capitol during an antisemitic pogrom inspired by Nazi propaganda, killing at least 179 Jews (historians estimate the numbers were much higher). Hundreds of Jews were raped, injured, and their homes and businesses looted. In testimony recorded for the USC Shoah Foundation Ruth admitted that, as an adult, she was haunted by a recurring nightmare in which a knife-wielding man was chasing her up the stairs in her school.

Nearly 60 years after the Farhud massacre in Iraq, fanatic Muslim terrorists in Pakistan shattered the Pearls’ lives when they killed “Danny,” as friends and family called him. In a video that captured his famous last words, Daniel said, “My father’s Jewish, my mother’s Jewish, I’m Jewish” (his last words inspired Ruth and Judea to co-edit the 2004 book, “I Am Jewish: Personal Reflections Inspired by the Last Words of Daniel Pearl,” which won the National Jewish Book Award.) In the video, Daniel also stated: “Back in the town of Bnei Brak, there is a street named after my great-grandfather, Chaim Pearl, who was one of the founders of the town.”

I asked Pearl why he thought Daniel had felt compelled to mention his great-grandfather in his final words.

“I kept thinking about it for many nights after,” Pearl admitted. “The street name was something that we rarely mentioned; I don’t know how he even came to think about it. I am fairly confident it was not something he was forced to divulge.

“I believe [Danny] was searching for comfort in his roots, and that’s where his mind fell upon the street name story; I guess it penetrated his mind deeper than we thought.” — Judea Pearl

“But,” Pearl continued, “thinking deeper into the reason why Danny said it under such stressful circumstances; I believe he was searching for comfort in his roots, and that’s where his mind fell upon the street name story; I guess it penetrated his mind deeper than we thought.”

“The Emancipation of Our Identity”

In a June 2021 Jewish Journal op-ed, Pearl highlighted the fear and harassment among pro-Israel students and faculty on campus, arguing, “Our generation of Jewish students are paying dearly for the failure of our academic leadership to acknowledge, assess and form a unified front to combat this academic terror.” The op-ed was one of dozens Pearl has written for this and other papers imploring the Jewish community to understand the dangers of what he calls “Zionophobia” on campus (the obsessive denial of the Jewish people’s right to a homeland). In his writing and lectures, Pearl offers brilliantly concrete ways to respond to the hideous onslaught of anti-Israel propaganda thousands of Jewish students and faculty face each year.

Pearl’s analytical mind and his in-depth knowledge of the Arab-Israeli conflict offer a precious treasure trove of wisdom and concrete solutions for the challenges facing pro-Israel Jews today.

Pearl’s analytical mind and his in-depth knowledge of the Arab-Israeli conflict offer a precious treasure trove of wisdom and concrete solutions for the challenges facing pro-Israel Jews today. The only problem? Few of us seem to be listening. In fact, we spend infinite time and resources arguing about what the definition of antisemitism ought to be, instead of using the one fighting word we have, “Zionophobia,” to pinpoint and expose the precise racist character of our enemies.

“When you call someone a ‘Zionophobe,’” Pearl said in a 2020 speech for Alums for Campus Fairness, it means: “If you deny my people’s right to a homeland, something is wrong with you … In fact, something very basic is wrong with you because you are trampling on universal principles of human rights, the right of a people to freedom, equality and dignity.”

In the speech, Pearl outlined two “weapons for reclaiming” Israel’s rightful place on campus: “The emancipation of our identity” and “the moralization of our cause.” Pearl explained: “By ‘emancipation of identity,’ I mean to stop seeking protection for Jewish students from antisemitism, and demand instead protection for Zionist students from anti-Zionism. By ‘moralizing our cause,’ I mean moving our fight from the legal to the moral arena, where we can win hands down.

“Jewish students will regain respect only when ‘Zionophobia’ becomes the ugliest word on campus,” he continued. “It depends on us; if we use it often enough—it will become the ugliest.”

Pearl is still waiting for more students and faculty to adopt his terminology. “I’m really mad,” he said. “Jewish leadership and writers just don’t use it [the word, ‘Zionophobe’]. And ‘antisemitism’ sounds so clumsy; it kills me. Whenever we Jews say ‘antisemitism,’ people start yawning and racists like Linda Sarsour rush to prove, black or white, that (1) they love Jews and (2) even Jews do not agree on what antisemitism is.”

For Pearl, education is a clear solution for combatting youth apathy toward Israel, “but it has to be done in the right way; we’re missing a very important component: storytelling. The whole Jewish psyche is story-driven, but even the basic Bible stories and the miraculous emergence of Israel aren’t being told by professional story tellers.”

Lately, he has begun efforts to persuade Holocaust memorial museums in America to create a special pavilion dedicated to Israel, which, he believes should be called “From the Ashes.”

“All those I talked to have said ‘Yes, it’s a great idea,’” he said, “but they haven’t done anything. Perhaps they are consulting their donors. What a loss of opportunity.”

Nevertheless, Pearl sees a personal duty to support fellow Zionists.

“I feel obligated to students who are harassed at UCLA and to faculty who are silenced. I feel an obligation to lift their spirits and show them how proud I feel about Israel, how easy it is to defend her when you know your history and when you are willing to address the core issues of the conflict.”

“I feel obligated to students who are harassed at UCLA and to faculty who are silenced,” he said. “I feel an obligation to lift their spirits and show them how proud I feel about Israel, how easy it is to defend her when you know your history and when you are willing to address the core issues of the conflict; my favorites are ‘settler colonialism’ and ‘occupation’; perhaps I will transfer some of this knowledge, pride, inspiration, and resilience to them.”

Again, the innate essence of Pearl, the sabra, infuses his worldview with unabashed pride.

On November 29 1947, with the approval of the United Nations Partition Plan that recommended a Jewish alongside an Arab state, eleven-year-old Pearl joined others in the streets, dancing, but didn’t quite understand why his father acted with such exuberance, shouting: “We have a state! The diaspora is over!”

“The idea didn’t register,” he said. “We were virtually in a state already; unofficially, we had a state in our minds when I was born.”

He still remembers the “anxiety in the streets,” the genocidal threats sounding from the radio, and the Egyptian air raids during the 1948 War of Independence (Pearl served in the Nachal division of the Israel Defense Forces from 1952-1956).

“I remember our neighbor, a nineteen-year-old boy, who smiled to us warmly, went to fight five armies, and came back in a coffin,” he said. “His mother remained glued to her window for the next ten years, waiting for him to come home.”

Though there would be other soldiers from Bnei Brak who perished in 1948, whether the son of the fish-seller or the shoemaker, the death of that particular young man, and his funeral, gave Judea Pearl his first experience in witnessing the irreparable brokenness caused by the violent loss of life.

The name of that IDF soldier, the neighbor with whom Pearl played as a child, and who lost his life in Israel’s War of Independence, was Daniel.

For more information about The Daniel Pearl Foundation, visit https://danielpearlfoundation.org/

***

On Religion with Dr. Judea Pearl

Jewish Journal: What compelled you to become an atheist at the age of 11?

Judea Pearl: I stood up on the roof of my grandfather’s house [in Bnei Brak] and looked down at the street. I saw all of the people busy shopping, wheeling and dealing, and thought that it’s impossible that there’s a God up there, and that these people won’t be worshiping Him, with fear and awe, 24 hours a day. The fact that they can do their business and survive while He sits there and watches is inconsistent. I concluded that there could not possibly be anyone who supervises what people are doing or thinking; it came to me like a thunderstorm, and it never bothered me again.

JJ: How did your Hasidic family respond?

JP: My family said it was a “temporary” teenage rebellion. My grandfather would say, “You don’t do that” every time I violated Shabbat. My father was more lenient. He said, “You can turn on the radio as long as the neighbors don’t hear.” That became our agreement.

JJ: Was there a moment during which Daniel went missing that you thought about praying?

JP: Yes, I remember sitting in a plane, praying “T’filat Haderech” (The Traveler’s Prayer). When you pray to God, God plays a poetic metaphor for things that you relate to, like a father, a mother, a teacher, a community … other forces which do exist; it gives you a sense of strength, because it evokes forces you’re familiar with, incarnated in the name of God.

JJ: And although you’re an atheist, you truly seem to appreciate the Torah.

JP: I terrifically appreciate the Torah because it is a medium baked with people’s experience and wisdom; it has been filtered by the generations, written by those who, in their time, were already smart enough to accumulate the wisdom of their forefathers and encode it poetically, in stories and laws. My favorite biblical story is the Book of Esther, particularly the verse in which Mordechai challenges Esther to step up to the plate for her people. I wish some of my silent Jewish colleagues would learn to emulate Esther.

JJ: If, after 120 years, you pass away and find that there is a God, what will you say?

JP: I’m going to say, “Come on, God, you really exist?” And He’ll say, “I tried to give you signals again and again, and you didn’t listen.” To which I’ll respond, “If you really were God, you would know how to give me clearer signals.”

JJ: Do you believe in the concept of a soul?

JP: Yes, it’s a piece of software called “soul,” which gives us the sensation that we transcend our body. I would ask you: Do you believe that computer software transcends the computer? Same with people; when you’re alive, you have a soul—a piece of software responsible for your consciousness and your relationship with the cosmos.

JJ: What inspires you to say the prayer for wine (“kiddush”) each Friday night?

JP: It’s my understanding that if I keep Shabbat traditions, my life will be more meaningful. I use Zoom to see my family and say kiddush every Friday night. Once, I was in a dialogue program with Muslim leaders in London. After, we went for dinner and sat down, and then it hit me: It’s Friday night. There were 12 imams around me and a couple of other Muslim leaders. I said, “I’m sorry, but it’s Friday night, and I have to do kiddush.” They were somewhat surprised, “But you said you’re an atheist,” to which I said, “You’re right, but today is really Friday night, and it’s really about heaven and earth.” So I asked the waiter to bring wine. Everyone stood up and I said the entire length of the kiddush prayer, beginning with Yom ha-shishi, Va-yechulu ha-shamayim ve-ha’aretz ve-chol tzeva’am.

JJ: Did Danny connect with Judaism?

JP: He never missed a Passover seder or fasting on Yom Kippur. A friend once asked him if he believed in life after death. He said, “I don’t know, I have more questions than answers, but I sure hope [the angel] Gabriel likes my music.”

Tabby Refael is a Los Angeles-based writer, speaker, and civic action activist. Follow her on Twitter @RefaelTabby

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.