“The embodiment of hillul ha-Shem [profaning God’s name] in Judaism today is the Kahane movement, whose latest political incarnation … has just been brought into the Israeli mainstream … with the active encouragement of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.”

— Yossi Klein Halevi

“We aren’t talking about an ideological partnership with the far-right but rather a legitimate ad hoc merger to establish a bloc that can prevent the left from taking power.”

— Dror Eydar

So which is it?

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s decision to push for a political deal that could help bring representatives of the far-right Kahane movement into the Knesset has prompted widespread anger and condemnation, including a rare rebuke from the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). The organization, retweeting a stronger condemnation of the American Jewish Committee (AJC), said it had “a longstanding policy not to meet with members of this racist and reprehensible party.”

AIPAC did not mention Netanyahu by name, nor the parties involved, but the message was clear: Netanyahu crossed a line.

Yair Lapid of the Kahol Lavan party called it a “shameful deal.” Well-known Israeli Rabbi Benny Lau likened it to “a destruction of the temple.” Roni Milo, a former minister of Netanyahu’s Likud party, argued that “no real student of [Zeev] Jabotinsky” — Likud’s ideological pillar — “can accept this.”

Was this condemnation justified? That depends on whether you think it is crucial for Israel to keep Netanyahu in his job as prime minister.

To understand this issue, one must begin with the scenario leading up to the deal — a product of Israel’s complicated electoral system. It goes like this: A coalition must have at least 62 seats in the Knesset. According to current polls, the Netanyahu coalition has a slim edge of one or two seats. Moreover, this edge is fragile because of Israel’s electoral threshold, which requires that a party must receive a minimum of 3.25 percent of the vote — about four seats — to even get into the Knesset. Two weeks ago, some of the parties that Netanyahu relies upon were dangerously close to coming up short of the threshold. In such a case, the votes they gain would be split proportionally between all parties based on a complicated formula.

So, Netanyahu faced a dilemma: If he did nothing, the right-wing parties could end up fighting and splitting apart, risking the majority that has kept him in power. But the prime minister has strong ambition and a long memory. He still remembers 1992, when the right was split and lost control of the Knesset when a few parties in its coalition failed by less than a percentage point to meet the threshold.

The result was the Yitzhak Rabin government, which led to a sharp turnaround in Israel’s policies, in particular the Oslo Accord with the Palestinians — a turnaround Netanyahu and most Israeli voters came to regret and reject.

As one watches the recent developments in Israel’s political arena and ponders Netanyahu’s actions, one must keep 1992 in mind. Because sometimes, a few percentage points have great consequences.

“The Arab Balad Party had representatives in the Knesset that assisted terrorists, supported Hezbollah and rooted for Syria’s Bashar Assad. Still, the Meretz party opposed the move to deny a state-funded pension from the founder of the party.”

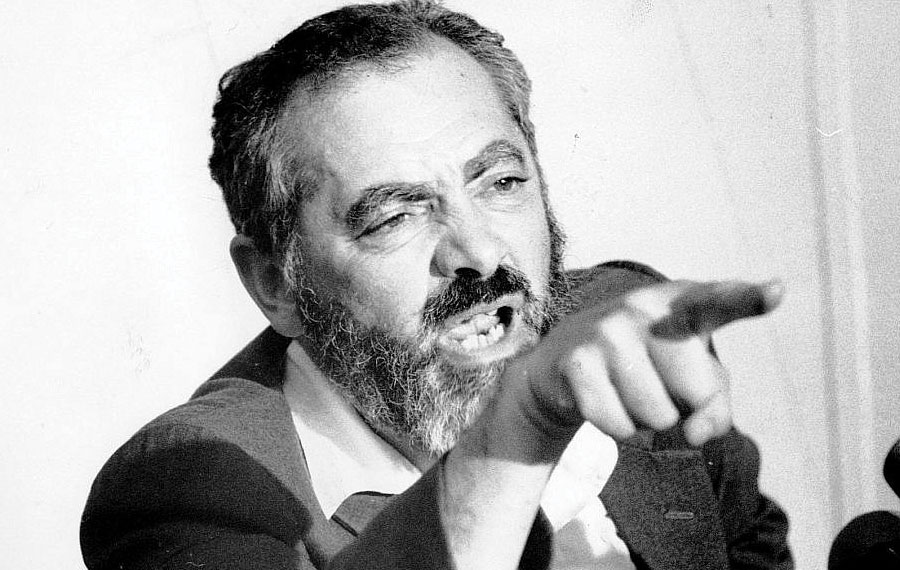

The leaders of Otzma Yehudit, a marginal entity on the far-right outskirts of Israel’s political system, consider themselves the disciples of Rabbi Meir Kahane, a Brooklyn-born activist known for his radical views. Before he was assassinated in a Manhattan hotel in 1990, Kahane served one term in the Knesset before Israel’s courts ruled him unfit to run again and the United States government declared his Kach party a terrorist group. His successors continue to call for the annexation of greater Israel and the expulsion of people whom they consider disloyal to Israel — by which they probably mean most Palestinians.

Kahane’s disciples have followers. Not very many, but not as few as one would hope. Their followers tend to be religious and right-wing. They are on the margins of the camp that holds Netanyahu’s coalition. To their left — yes, the term “left” is a little awkward in such context — is the right-wing religious party, Jewish Home. It is a party in crisis. Its two charismatic leaders, Ministers Naftali Bennett and Ayeled Shaked, departed to form the New Right Party, and some voters are going to leave with them.

Enter Netanyahu and his long memory of political disasters. If the Jewish Home party doesn’t cross the threshold, the right could lose close to four seats. Netanyau’s coalition currently does not have two — let alone four — seats to spare. So, he took action: He leaned hard on Jewish Home’s leaders to include two Kahanists on their list. If all right-wing religious parties join forces, their list will surely cross the threshold. No votes will be lost. And Netanyahu will get his coalition.

What is the meaning of all this?

When Kahane was elected, many members of parliament made sure to excuse themselves from the main hall when he was making speeches. Then they changed the law, forbidding parties that reject democracy or support racist ideas from running for the Knesset. In 1988, Kahane could no longer run. The Supreme Court sealed his party’s fate by declaring that its purposes and actions were “clearly racist.”

Kahane did not have much impact when he was a Knesset member, nor did any of his disciples. They formed new groups and parties and are allowed to run, unless or until the courts say otherwise. Michael Ben-Ari, one of two Kahanist activists who could become Knesset members thanks to the deal, was a member from 2009 to 2013 and no one seemed to notice. From time to time he would make a controversial comment or stage a provocative protest, but his impact on Israel’s policies was marginal and his presence was contained. Netanyahu probably believes that if Ben-Ari were to become a Knesset member again, the same scenario would likely be repeated.

No serious observer suspects that Netanyahu is a supporter of the Kahane ideology. He is not. For him, the question is one of balance: Which would be worse — one Kahanist in the Knesset or a government headed by someone other than Netanyahu?

Let me suggest an answer: Neither will be the end of the world.

This is not the first time a Kahanist will be in the Knesset. Israel survived Kahanists before, including the original. Similarly, Israel existed before Netanyahu and, hopefully, it is going to survive his departure from office.

Obviously, not all people agree with this assessment — namely, the prime minister.

Netanyahu believes that keeping him as the leader of the government is essential for Israel’s future — so essential that he is justified in forging a dirty deal with the Kahanists. If one agrees that the country will be in grave danger without him, an ugly deal with a marginal faction of extremists would seem a small price to pay.

Does anyone believe such foolishness? Does anyone really think that Netanyahu is so essential to Israel?

You might be surprised to learn that the answer is yes. About half of Israel’s population is going to vote for a Netanyahu coalition, despite the Kahane deal. These Israelis are not happy about having a reprehensible Kahane ideology in the Knesset, but they accept it as an ugly political reality preferable to the alternative.

They accept it because they remember Oslo and understand that political purism can be dangerous to the practitioner. They also accept it because they believe the attack on Netanyahu is hypocritical. Parties that are denouncing the prime minister for letting in Kahanists were not so keen to censor problematic political elements on the left when such opportunities presented themselves. The Arab Balad Party had representatives in the Knesset that assisted terrorists, supported Hezbollah and rooted for Syria’s Bashar Assad. Still, the Meretz party opposed the move to deny a state-funded pension from the founder of the party, who escaped Israel when the authorities realized he was a Hezbollah spy.

But even without going so far as blaming the left for relying on supporters of terrorism, Israeli right-wingers have reasons to giggle when the left accuses them of cutting dirty deals. Was not Oslo a result of a dirty deal?

Netanyahu can still recount in detail how the Rabin government, struggling to form a slim majority to pass what is known as Oslo B — an agreement that gave the Palestinians self-rule in some areas — essentially bought the votes of two Knesset members (they got positions and benefits in exchange for their votes).

Gonen Segev, one of the two politicians who gave Rabin his 61-59 majority, was just sentenced to 11 years in prison, having been convicted for spying for Iran. That’s right, the man without whom there would be no Oslo Accord is now a convicted spy.

Of course, a large group of people see the Kahane deal as a red line that should not be crossed, no matter the circumstances or consequences.

“There’s a difference between a racist party entering the Knesset — the fringes of Israeli democracy can unfortunately contain such elements — and their being encouraged by the prime minister,” said Yohanan Plesner of Israel’s Democracy Institute.

Rabbi Lau made a similar point: “In the name of love for the land of Israel and maintaining sovereignty over it, the prime minister enticed the followers of Rabbi Kook [from the Jewish Home party] to make the abomination of racism kosher and enable it to enter the gates of the Knesset.”

Both are right. The involvement of Netanyahu in cutting such a deal potentially could confer a grain of legitimacy on an abhorrent ideology.

So what would opponents of the deal expect?

Apparently, they expect Netanyahu and his supporters to tolerate the prospect of a loss in the next election — and much more. “Jewish safety and sovereignty cannot come at the expense of Palestinian rights, freedoms and dignity,” wrote Batya Ungar-Sargon, the opinion editor at The Forward. She is extremely angry at Israel and at the deal. She also has her priorities set: Palestinian rights first, safety second. That is, the safety of me and my children. Naturally, with such priorities, condemning the Kahane deal is quite easy, as it allows for no argument in favor of the deal.

“No serious observer suspects that Netanyahu is a supporter of the Kahane ideology. He is not. For him, the question is one of balance: Which would be worse — one Kahanist in the Knesset or a government headed by someone other than Netanyahu?”

Right-wing Israelis are not receptive to complaints about dirty political deals, even less so when those arguments come from people in the United States — people who won’t suffer the consequences if Israel’s election produces a bad outcome.

Israel Hayom, Israel’s most popular newspaper, which is highly supportive of Netanyahu, was critical of AIPAC’s tweet: “For years, the left has counted in every coalition calculation the pro-Palestinian radical left along with it. This included Arab parties working to destroy Israel’s Jewishness by claiming that it was ‘racism.’ … Where was AIPAC so far, why did we not hear this moral preaching to the Israeli left about this alliance?”

On social media, as usual, the response was sometimes more brutal.

Irit Linur, a very well-known, controversial and popular Israeli novelist, radio personality and commentator, posted: “If the righteous Jews of the United States have the will and the energy to fight abhorrent racism that operates under the auspices of parliamentary legitimacy, let them refer to Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, two anti-Semitic congresswomen, both of whom doubt Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state, and recently accused AIPAC of bribing American politicians to support Israel. In my opinion, it is a scandal that a legitimate party accepts two anti-Semitic racists such as Omar and Tlaib. … So if AIPAC is already at the preaching mode, take care of your party first, in the country where you are a citizen, and mess with our parties when you become citizens of the State of Israel.”

Many Israelis liked the post, giving it 2,100 likes, 268 comments and 323 shares.

For most Israelis, politics is not always easy. Had they been told in advance that the only way to ensure their safety was to have two Kahane representatives in the Knesset, I assume most of them would have grudgingly accepted the deal. And in fact, that is exactly the message conveyed by the prime minister’s actions: “It’s either the deal or your safety — because a coalition other than mine is not going to keep you safe.”

Do I buy this argument? No. I abhor the Kahane deal.

But for the reasons I’ve attempted to explain, I understand why other Israelis do.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.