“Pray for Israel — Act for Israel”

That was the fervent banner headline I splashed across the front page of Heritage, a small Jewish weekly in Los Angeles, on Monday, June 5, 1967.

The time was 8 p.m. in the Middle East, but only 10 a.m. in Los Angeles. As I drove to the paper’s printing plant in Culver City, the car radio blasted news of Arab boasts that their forces were about to take Tel Aviv and throw the trembling Zionists into the sea.

Normally, I would have been at my regular job as a science writer at UCLA, but Herb Brin, the editor, circulation manager, advertising director and everything else at Heritage, had left a week earlier on a press trip to Israel and had asked me to fill in, reading the page proofs of the week’s edition.

I threw out whatever bar mitzvah extravaganza was gracing the front page and, at a fever pitch, wrote about the catastrophe again facing the Jewish people, a scant 22 years after the end of the Holocaust, and implored readers to rally around the defenders of the Jewish state.

The paper was delivered to its readers on Friday, June 9. By that time, of course, the world knew that Israeli forces had won a stunning victory. So quickly had events moved that my stirring headline of four days earlier already had the feel of ancient history.

Two weeks later, I looked back on that tumultuous month and wrote, “The three weeks — from the beginning of the crisis to the final cease fire — were one of those rare periods of total emotional immersion which a man remembers to his dying day.

“Who will forget the midnight calls, the morning and evening emergency meetings, the knuckle-cracking hours glued to the radio and the TV screen, the committee resolutions that were outpaced by events as soon as they were passed, the stomach-knotting hours and days waiting for a telegram from relatives in Israel?”

Besides changing the map and power balance of the region, Israel’s victory had a profound psychological impact on American Jews — and how they were viewed by their gentile countrymen — even exceeding the impact of the 1948 war that secured the independence of Israel.

In 1967, the American Jewish community, molded for decades by a “don’t make waves” mentality — which shamefully persisted throughout the Holocaust — finally found its voice. Not only a voice, but the communal body stiffened its collective spine, stopped worrying about accusations of dual loyalty and pitched in as all Americans did after Pearl Harbor.

Young Jews, who were ardently protesting against the United States’ role in the Vietnam War, clamored to go to Israel to join the fighting or work the land. Academicians and intellectuals, usually busy concentrating on their research, joined mass demonstrations. Israel-related agencies were besieged by thousands of instant donors — the wealthy waving million-dollar checks, the poorer hocking valuables or taking out loans to make their contributions.

To their surprise, even timorous Jews discovered that the great majority of their countrymen, whose prevalent anti-Semitism had only been spurred by Jewish success in medicine, the arts and commerce, now expressed unbounded admiration that the Jews in Israel could fight and win against all odds.

While past generations of American (and European) Jews had sought assimilation and defense against anti-Semitism, the “new” Jew accepted that the fates of Israel and Diaspora Jews were inevitably linked and that the Jewish state was the only guarantor against a future Holocaust.

Jokes at the time had it that the Pentagon had asked Gen. Moshe Dayan, leader of the Israeli armed forces, for advice on how to win the Vietnam War.

Time and Life, two of the most influential American magazines at the time, had followed a pro-Arab line for years but now swung to the Israeli side (the death of founder and publisher Henry Luce three months earlier may have played a role in the changed stance).

And Los Angeles Jews joined their co-religionists across the country in actions large and small.

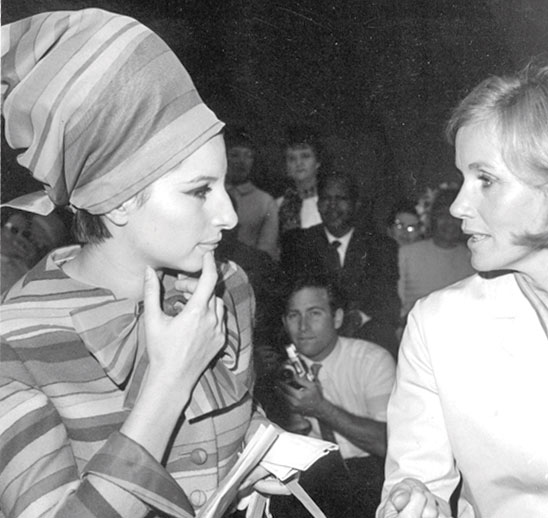

A hastily organized community rally was held June 11 at the Hollywood Bowl, drawing 20,000 people as well as 4,000 pledges of large and small gifts. In attendance were California Gov. Ronald Reagan, U.S. Sen. George Murphy, Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty and dozens of Hollywood celebrities, such as Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Danny Kaye and Carl Reiner.

The board of directors of the Hillcrest Country Club, founded by and for Jews, mandated that every member had to contribute to the United Jewish Appeal’s Israel Emergency Fund.

At UCLA, some 1,000 students attended a vigil and 200 signed up for volunteer service in Israel. Jews flocked to synagogues in unprecedented numbers. With minor variations, similar responses took place in every major American city.

One of my favorite 1967 war anecdotes revolved around Mike Elkins, at various times a Hollywood scriptwriter, an Office of Strategic Services operator during World War II and a labor union organizer.

and Eva Marie Saint at the rally for Israel at the Hollywood Bowl. Photo courtesy of Barbra Streisand Archives

I met Mike in 1948, when I was attending UC Berkeley, and looking for some way to get to the newly established State of Israel and join the fighting. Someone advised me to contact Elkins, then a business agent for the butchers’ union in San Francisco. I walked into his office unannounced and told him I wanted him to get me to Israel to participate in the War of Independence.

Elkins blanched, told me he had set up an elaborate vetting and security system to keep American authorities from discovering his then-highly illegal activity, and here I had just walked in.

In any case, he found it prudent to leave the United States for Israel later in 1948 and, after a year on a kibbutz, found a job as a stringer for the BBC and other media outlets.

On June 5, 1967, Elkins went to the Knesset and ran into a knot of highly excited politicians, from whom Elkins gathered that Israeli fighter planes already had wiped out the air forces of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. Elkins immediately phoned his BBC editor in London and announced, “Israel has won the war.”

The flabbergasted editor thought that Elkins had lost his mind. Cairo, Damascus and Amman were transmitting a string of bulletins previewing the utter defeat of the Zionist entity.

Elkins, however, stuck to his guns. The BBC editor finally gave in but warned Elkins that if he were proven wrong, this would be his last day as a BBC correspondent.

Mike Elkins kept his job and lived and died in Jerusalem.