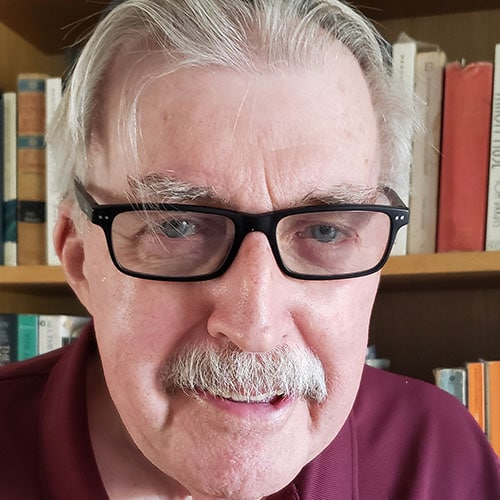

Minde Ornelas

Minde Ornelas Unlike many of her fellow educators, Minde Ornelas has gone to work every day since the pandemic began. “We were lucky enough to be considered essential workers, and so we were allowed to remain open,” said the longtime director of the Gan Chabad preschool in the Pico-Robertson neighborhood.

Classes continued uninterrupted, the first three and a half months on Zoom, and in-person ever since July 2020, “because people needed to go to work,” Ornelas said.

“Preschool is really considered ‘daycare’ in the eyes of the Dept. of Social Services, which is our governing agency.”

After 32 years working in preschools, Ornelas said the asserted downgrade is “a tiny bit offensive. There is a twinge of ‘yikes!’ It is not demeaning, but it feels invalidating, as if people don’t understand the true importance of what we are doing. We are not babysitting. We are educators.”

The notion that the concepts of daycare and preschool are almost interchangeable appears to be unique to the United States.

“In other countries,” Ornelas said, “people do not have that impression. Other countries value early childhood education so much more than we do here in America. I don’t think anyone has discovered why that is so.”

In distinguishing between daycare and preschool, Ornelas suggests that when many people hear the term “daycare,” they imagine “a slight connotation of just watching children play, meaning the materials are not well-thought-out, not purposeful. You are just keeping the children busy, out of trouble, until they are picked up—as opposed to being a preschool teacher, a real educator.”

Her students are two, three, four and five years old.

Ornelas, who has a B.A. in Early Childhood Education from American Jewish University, said that while a given scene might look like simply playing to a parent or onlooker, “we know that every single piece of material is purposeful, useful. The children gain from their environment. We carefully prepare the environment for the children’s learning. We don’t just put out things and tell them ‘Go play and don’t get in trouble before your mother comes.’ Much more thought goes into the environment to prepare for the children’s learning.”

A mother of two college-age daughters, Ornelas began her teaching career when she was 18 years old.

She has been in a self-educating mode ever since.

“I work on constant self-growth, constant learning,” said Ornelas. “I am constantly refreshing what I know, researching new philosophies. We are learning so much more about children’s brains, about how they learn—so that I can be a proper observer of teachers, of parents and of children.

“I learn by reading, by researching, by attending webinars. The Bureau of Jewish Education offers lots of continued development, ongoing education. You have to keep educating yourself.”

So how would Ornelas, who leads a staff of 15 teachers, respond to a skeptic who says, “Preschool teachers are there mainly to make sure nothing bad happens to the children”?

“There is so much I would like to tell people like that,” she said.

“Unfortunately, many [people] don’t understand children’s play. They don’t understand what learning looks like in a young child. They think learning is a product that is quantifiable. That means I tell you something, and you need to repeat it back to me. You need to show me that you learned it. Prove it to me.

“But a true educator of young children understands what is happening inside of a child’s brain that really lays the foundation for a higher order of thinking for skills they will need later on. This is when the connections are made in their brain. This is the foundation for their future learning.”

Among the numerous changes in preschool education since her rookie year of 1989, Ornelas mentioned the philosophy of Reggio Emilia, named for a community in Italy.

“This curriculum is driven by the children’s interests, not by the teacher’s interests,” she said. “Children learn much more when they can study a subject in depth, according to things that are exciting for them. I can tell a child, ‘You are going to learn about dinosaurs because I am telling you, that’s what is important in your little life.’ But a child may be interested in learning about trucks because he is all about trucks in his little life.

“The subjects we are teaching,” said Ornelas, “are about a means to an end. The end is development. The end is excitement. The end is the desire to learn, to be excited about information and self-discovery, discovery about the world all on their own in realizing how capable they are. All of this instead of the teacher telling them and putting the learning into a box.”

Each year she is reminded anew that children are naturally excited about learning, “but I think schools, teachers, parents sometimes squash that excitement to a degree because of their agenda.”

She said it can be more important for some teachers to achieve their daily agenda than to focus on motivating, inspiring a child about learning. “Sometimes a teacher might have her agenda and not take into consideration what a child is interested in,” Ornelas said.

“I have always been an observer as an educator. You can’t be a good educator without being a good observer.”

When asked whether she could have been a high school teacher, Ornelas was quick to answer.

In a word, no.

“I am a person who likes to make a connection,” Ornelas said. “I don’t feel that learning really happens undisciplined. First you have to make the emotional connection. You can’t ask for discipline or real learning to happen when there is not a trust that happens first.

“Children need to have a relationship with you for you to have real expectations on them, to respect you. You can’t discipline without first establishing a relationship. For me, between barriers, it’s very disconnecting on an emotional level.

“I teach little kids, and they are physical people. They like to be near you, close to you. I think older students have distance [issues]. It is harder to make the connection. But that is who I am.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.