After I spoke on a panel, the panel’s moderator stood behind me, reiterating the point I’d just made, while resting his palm on the top of my shoulder, his fingers extending to my clavicle. It was public. It wasn’t sexual. It wasn’t malevolent. It wasn’t a grope, assault or abuse. And it certainly wasn’t rape. God forbid that it is any of those things for me or anyone, ever. But it was utterly unnecessary. And it made me uncomfortable.

Instead of owning my discomfort, I made excuses. This was no big deal. He held no power, no ability to inflict physical or professional harm. It was generational: The intent was avuncular or paternal, even if it felt patronizing and invasive. It was vestigial discomfort from messages I received about touch in Orthodox Jewish schools. It was my inner New Yorker, dormant after a decade of California grooviness, awakening to someone touching me unexpectedly from behind. So if it wasn’t “wrong,” then why did it feel that way?

Talking with friends about sexual harassment, the imbalance of power and lack of gender equity in the Jewish community is a regular conversation for me. Whether it’s equal pay or equal representation, these discussions are multinational and local, playing out against the greater conversations around #MeToo, chronicling sexual harassment and assault, and Time’s Up, a call to expand opportunities for women, to “join the resistance” and “smash the patriarchy.”

From rabbinic times to present day, men have owned most Jewish leadership positions. And even in a moment that’s tuned in to the conversation on gender equality, the Forward’s 2017 salary survey of Jewish communal organizations’ leadership shows only eight women listed in the top 56. As “Yael,” a former Jewish nonprofit professional, told me, women in Jewish organizations “know we’re there to service these men, stroke their egos, be the good girls and make sure they get what they need.” This expectation validates the status quo: men lead, women support.

Talking with friends about sexual harassment, the imbalance of power and lack of gender equity in the Jewish community is a regular conversation for me.

With this hierarchy so systemic, power is consequently at an imbalance. Yael was in her 20s when her supervisor, 25 years her senior, would comment on her body, make her uncomfortable by touching her arm, and “go up to the line but didn’t really cross it.” She struggled with infertility; her boss suggested it was because the sex wasn’t good. But he was also a father figure who “made me feel cared for as a person and as a professional. … If I could shunt off the creepy stuff, it would be great. In the Jewish community, boundaries are down and everyone acts like they’re related, anyway. He took advantage of that intimacy and lack of boundaries.”

If Jewish organizations and institutions operate on the perception that we’re all family, why shouldn’t we all be able to show blunt appreciation and affection that sometimes feels smothering or oppressive? Because, family often comes with complicated emotions attached, but that’s not something everyone wants in their workplace.

Think about the role of touch in your professional environment: showing closeness, expressing support or bridging a conflict. “Job well done!” — handshake, high-five or fist bump. “So great seeing you again!” — hug, back slap, European air kiss. “I’m so sorry for your loss” — handshake, embrace, hand on shoulder to impart strength.

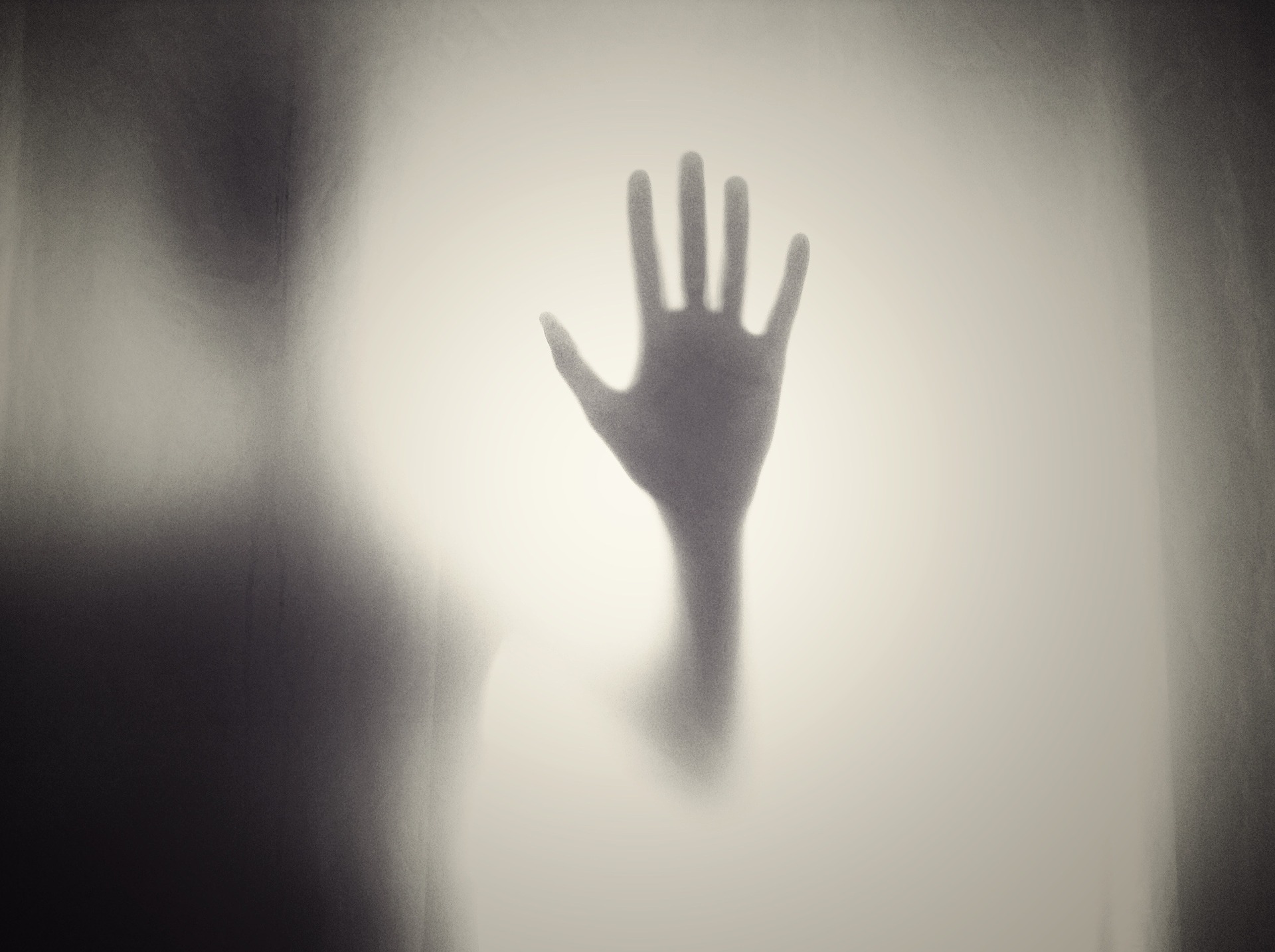

Touch asserts dominance; a person with more status can touch one with less. The #MeToo label includes stories of assault but also of lack of respect and abuse of power in the workplace.

Touch is valuable and powerful, but how that physical contact is received is situational. A hug from your sibling isn’t the same as a hug from a colleague. When my mother died, some embraces healed, others hurt; on Sept. 11, 2001, I accepted contact from just about anyone. And with shomer negiah (abstaining from touching the opposite sex) a value for some in our community, we should think twice before reaching out to touch someone.

The complication around touch predates any hashtag; in the time of #MeToo and Time’s Up, being in the Jewish communal workspace adds a layer to an already complicated conversational space. In this reactive world, it’s worth taking a beat before we reach out and touch someone, not because we’re afraid of litigation but because touch is too powerful to be used irresponsibly.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.