After a week in Israel — my first visit there — my overall assessment of its state of the environment is that there is room for both optimism and pessimism. Israel’s environmental health depends on the country taking decisive steps, both large and small, to reverse decades of damage.

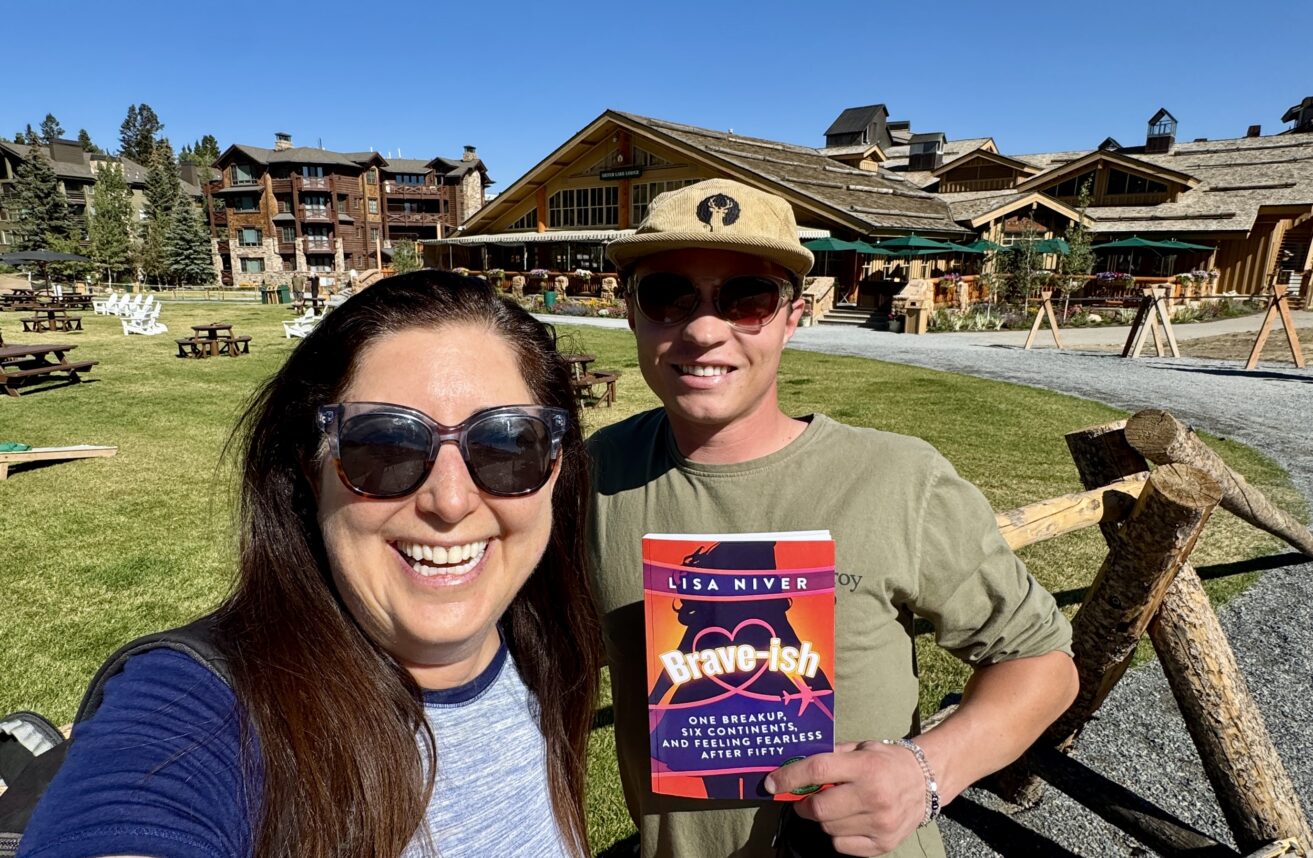

I arrived in Israel last month to discuss environmental issues with leaders there. I joined Los Angeles city and county officials and activists led by Evan Kaizer on a trip arranged through the L.A. Jewish Federation’s Tel Aviv-Los Angeles Partnership. As the president of Heal the Bay, the nonprofit organization dedicated to improving Southern California’s coastal waters and watersheds, I came to share stories about water quality and supply, sustainability and river restoration.

Also, we met with several leaders from the environmental NGO community, the mayor of Tel Aviv and his staff, representatives from the Ministry of Environmental Protection, academics and even a couple of members of the Knesset.

From an environmentalist’s point of view, Israel is a nation of overwhelming contrasts. On the one hand, every building seems to have a solar water heater, every bathroom has dual flush toilets and the nation recycles an astounding 70 percent of its wastewater. On the other, the nation gets about two-thirds of its energy from coal, completely abuses rivers through sewage discharges and flow extractions for agriculture, and dumps massive amounts of sewage sludge into the Mediterranean Sea.

Israel is struggling with its environmental identity. As a highly educated, high-tech nation, the country is poised to be a major force in the global solar market. But despite all the innovation, Israelis have yet to build major solar facilities to wean themselves from coal. In fact, their energy use continues to rise due to increasing reliance on desalination for water supply, a love affair with air conditioners, and massive pump infrastructure to deliver potable and recycled water throughout the New Jersey-sized nation of 7 million. (However it is worth noting that Israelis are still much more efficient per capita than Americans.)

Security and water supply remain the dominant issues for Israel. Environmental concerns have only emerged in the last 15 years or so. The NGO movement is growing, but still has a long way to go. The Israel Union for Environmental Defense (IUED), led by Tzipi Iser-Itzik, is well on its way to becoming the Natural Resources Defense Council of this nation, having recently spearheaded the successful effort to finally create the first Clean Water Act for Israel. The Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel is playing the Sierra Club role. I spent some time talking to Sagit Rogenstein from Zalul, Israel’s clean water and clean ocean group, and although they have great aspirations and energy, their next step should be partnering with the Waterkeeper Alliance (over 180 Keepers worldwide) to take their efforts to the next level. Also, I met with Gil Ya’acov, the executive director of Green Course, and his group plays the Environment California role with tremendous success in grass-roots organizing, especially on college campuses.

The most impressive environmental leader I met on the trip was Alon Tal, the founder of the IUED in 1990 and an environmental law professor at Ben-Gurion University. Tal recently received the Lifetime Achievement Award for Environmental Protection from the environmental ministry for his decades of effort. In addition, Tal authored “Pollution in A Promise Land: An Environmental History of Israel.”

Tal gets the big picture on the problems of environmental protection and integrated water supply management in Israel and the Middle East, and he’s very active representing Israel at the UN on desertification issues. In addition, he plans to play a role in Copenhagen on climate change in December. Tal understands that Israel’s environmental future depends on its relationships with the international community including the Middle East, and greater coordination between the NGOs, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Knesset.

Based on my conversations with a number of current and former staff members at the environmental ministry, the next essential area for growth in the Israeli environmental movement involves better working relationships between NGOs and the ministry.

Also, the regulatory and legal framework in Israel still has some glaring loopholes, especially on clean water and enforcement responsibility. Israel’s complex regulatory system involving numerous ministries makes progress exceedingly slow and difficult. However, eco-minded Israelis all agree that there is reason for optimism because of greater public awareness, growing elected sustainability leadership, and a few recent environmental wins, such as getting rid of fish pens for aquaculture off the coral reefs of Eilat.

A closer look at Israel’s water issues illustrates the nation’s environmental problems, yet provides reasons for optimism. Many Americans first became aware of Israel’s polluted rivers after a horrific bridge collapse on the Yarkon River near Tel Aviv in 1997. An Australian athlete who fell into the toxic waters actually died from exposure to pollution. The catastrophic event catalyzed a movement to clean up and restore Tel Aviv’s major river and others in Israel.

That terrible event played in my mind as I sat with my Israeli colleagues. There are many connection points between the L.A. River Revitalization Plan and the Yarkon River Authority’s efforts to restore its waters. Both rivers run through major cities, both are sewage effluent-dominated in dry weather with recently upgraded sewage treatment plants providing river flows, and both bodies have been engineered to the point that restoration is impossible.

Recently, the Yarkon has received millions of gallons of raw sewage from a broken sewer line in Or Yehuda, a small town upstream from Tel Aviv. Over the last two months, the ongoing spill has resulted in little more than finger pointing. Infrastructure collapses are hardly restricted to the Land of Milk and Honey. We’ve had more than our share here in Los Angeles. However, the response to the problem may be unique to Israel. There’s a long list of government entities that claim that the responsibility for the sewer line breakage lies elsewhere. The public outcry from impacted businesses like hotels and fishing interests has largely been ignored. Although Tel Aviv suffered a similar fate in 2003 following a large sewer collapse, they have not demanded a sewer repair, despite the fact their famous beaches have been closed by the Ministry of Health the last two months. The Ministry of Environmental Protection, Israel’s EPA equivalent, largely sits on the sidelines because it’s a local issue. The Yarkon River Authority, the Marine and Coastal Division and the Water and Streams Division of the environmental ministry all claim they don’t have jurisdiction. Inexplicably, the ministry’s so-called Green Police, as well as the minister himself and his director general did not seize leadership until recently to solve the issue. In addition, the local NGOs did not sue to force an immediate repair of the public health and environmental pollution hazard.

With money scarce, the approach of choice was blaming others while Tel Aviv’s miles of beaches remained closed for two months. The closure continued for days, weeks and on to two months, yet no one repairs the broken sewer line despite the constant media attention and the outcry from beach-dependent businesses.

In L.A. County, no sewage spill would last for more than a day. City or County Sanitation District crews would respond immediately and work around the clock until the spill was repaired. Until Israel makes public health protection through improving sewer infrastructure and maintenance a top environmental priority, sewage spills and beach closures will continue to plague the nation’s rivers and beaches.

Yael Mason, an Israeli friend of mine from my UCLA days, is an environmental chemist with years of experience at Israel’s Ministry of Environmental Protection. During my trip to Israel, Yael gave me an overview on the water management governance infrastructure. Israel’s Water Authority makes the water supply decisions for Israel, and its power seems to trump the government’s environmental and parks departments. Drinking water and agricultural irrigation supplies are what matters most in the small nation. As a result, Israel’s rivers are all highly degraded and many largely serve as irrigation ditches and disposal sites for wastewater.

Yael set me up on a river tour with the nation’s premier watershed management and river restoration expert, Eyal Yaffe. Yaffe and I explored the small Soreq River, which winds through farmland not too far from the city of Rehovot. He has been leading the effort to enhance the river, hoping to transform it from being a straight irrigation ditch into a meandering stream with buffer zones of swales and olive trees. A pragmatist, he readily admitted that this Herculean effort is not a restoration.

Among the obstacles preventing a true rehabilitation: farming to the river’s edge, enormous water supply needs, and strict drainage management (a separate drainage authority is a strong agency here). By the end of the tour, I was impressed by Yaffe’s efforts to provide some life to the Soreq. He has created buffers in many places. He has persuaded farmers to change their drainage patterns to reduce soil loss and sedimentation in the river. He has replaced concrete armoring of near vertical stream banks with gently sloping banks made of riprap that allows some native vegetation to thrive along the banks. Numerous straightened lengths of channel have been replaced with meanders. And ugly concrete monstrosities called flow dissipators have been forsaken for more natural stone waterfalls and pools with downstream riffles and runs.

Despite all of these physical improvements, Yaffe knows that the water in the river, nearly black from effluent from Jerusalem, has nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations too high for a healthy river ecosystem. But Yaffe is a patient man and he understands that true restoration is measured in decades, not years.

His passion for watershed management and stream restoration was contagious and consuming. He described efforts to fix Israel’s most polluted river, the Kishon and plans to rehabilitate the Jordan River, which flows to the Sea of Galilee and provides most of Israel’s water supply, as well as a significant portion for the nation of Jordan.

Water quality at these rivers has improved dramatically, but still has a long way to go to reach healthy levels. After spending the afternoon and evening with Yaffe, I couldn’t envision a promising future for Israel’s rivers. Those who want to revive them face constant pressures on such a small water supply, and the relentless needs of farmers, industry and all Israelis and Palestinians. Even Yaffe’s relentless optimism was not enough to give me hope.

The next day, Yael and her husband Tony, took me and my son Jake to Lake Kinneret and the Golan Heights. When I first saw the mighty Jordan River flowing from the algal-bloom impacted Lake Kinneret, my pessimism was affirmed. After all, the lake was pumped far below healthy levels and the consequences of a eutrophied lake were clear.

Above the lake, the Jordan seemed in better shape, but not exactly a healthy river. Not until later that day, as we drove to the border of Lebanon and up the Golan Heights overlooking Syria, did I truly understand the potential for river restoration in Israel.

The upper Jordan is a river. There are riffles, runs and pools. In fact, river rafting has become very popular in the Galilee. Willows and other native plants dot the riverbanks. As we moved closer to the source of the Jordan in the Golan Heights, the river became more wild. The view of the river’s source, the 9,000-foot, snow-capped Mount Hermon, made me realize that Yaffe has cause for optimism. If they can get the upper Jordan restored, then there is hope for the rest of Israel’s rivers.

Success won’t come easily, but nothing ever does in Israel. Clean water laws need to be tightened to protect aquatic life in fresh water. Industrial waste programs must improve. Regulatory frameworks need to be created that foster watershed management rather than prevent it. Sewer infrastructure must be built or replaced and sewage treatment plant improvements are needed. Most importantly, nature needs a place in the water supply equation. As long as people like Eyal Yaffe continue to tirelessly advocate for river protection and lead by example, then Israel’s rivers have a fighting chance.